Jews are obsessed with storytelling, and by extension, our grandparents.

For cultural humanist Jews like me, intergenerational storytelling informs our identities, social activism and (less consciously) our anxieties. They’re performed loudly with chaotic gestures over white laced Shabbat tablecloths, whispered with disobedience in shul (always accompanied by arm tickling) and recited solemnly over gravestones bestrewn with small pebbles signifying the presence of mourners.

I had the very rare fortune of an upbringing guided by two great-grandparents, three grandparents and my soulmate-friend, Eddie Jaku – a Holocaust survivor, storyteller and community leader who passed away last month after 101 years on earth.

Like an alchemist, Eddie spun his dark and harrowing survival of the Holocaust into a tale of the sincerest love for humankind. Later in life and after many decades of silence, Eddie cautiously began sharing his story and disseminating his message of love onto everyone who would listen. His audiences grew from congregants to museum visitors, school cohorts and, later, to auditoriums of thousands.

Our friendship began when I was in my first year of high school and working at a salad bar. Every Sunday, a formally dressed man would approach the counter and order the exact same sandwich, to be cut into two and separated into two paper bags. The man, with a thick European accent, French with flecks of German, would seek me out from my other bandana-wearing colleagues and, if I wasn’t at front of house, I would get a holler to alert me to his presence. After many months of this weekly and mostly silent ritual, the man appeared with a badge affixed to his tweed jacket spelling out “zachor,” or remember. I turned around my purposefully backward necklace that spelled out Chana, my Hebrew name. We both beamed. We exchanged numbers and agreed that I would go and listen to him speak in the coming weeks.

As many others will tell you, the first time I heard Eddie share his story, I was shaken and recalibrated. I listened as he retold in meditative slowness his experiences in Auschwitz and Buchenwald, on endless pilgrimages through the Black Forest, in cattle cars and in hiding, and his shrewd escapes in a truly unintelligible story of survival. In my inconsolable state, Eddie held me for a long time afterwards, whispering, “Every breath a blessing,” into my ear.

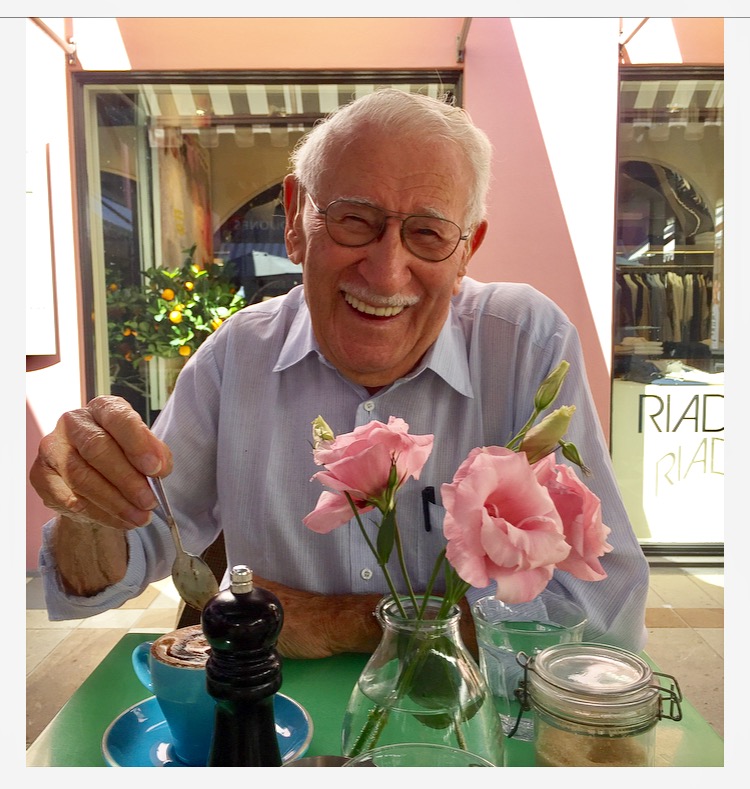

Since then, Eddie and I met every few months for coffee, pastries and never-ending debate. To him, I was a tiresome leftist Jewess of the inner city with “in time, futile” opinions on social order and inequality. To me, Eddie was a staunch debater, his views at times dubious but his methods relentlessly effective: wistful French aphorisms and a mischievous smile. At every café we met we would overstay our visit and, ushered out by impatient waiters, find a new spot on a park bench nearby. Matters for discussion included eastern European Jewish mythology, police powers, doctrines of mechanical engineering and inevitably, and what it means to be a modern Jew (subtopics encompassed prosciutto and the practice of kapara). When our minds and appetites settled, Eddie would hold both my hands at once, pressed together inside his giant grapey fingers, infinite in length, and say: “One flower is my garden, and one good friend, my entire world.”

I followed Eddie’s talks, interviews and writings. He soon called himself “the happiest man on earth.”

There was something about Eddie’s limitless capacity for happiness that seemed to contradict those qualities in him that I came to know so well. Eddie exhibited the most quintessential yekke, or German-Jewish, characteristics – always impeccably dressed, punctual and prepared with pockets full of small and practical objects he could procure in an instant: a hair comb, business cards for motor mechanics and letters of admiration. His unceasing and unaffected optimism seemed to exist in direct opposition to his rational philosophy and meticulous way of life. Before all else, Eddie learned to be an engineer. He was a man of rigour, austerity and precision. Eddie cited his dexterous motor skills and mathematical mind as his most valuable attributes without which he would not have succeeded in his survival. He prided himself on these qualities, and over lunch would change the battery inside his hearing aid in one nimble and swift gesture. “This is how I survived,” he would remind me, motioning with one hand at the motionless other.

Eddie recounted his dreams and time-tested memories with accuracy and lucid intellect. Such a detailed thinker, Eddie often reminded me of the time he saw a man in a market square in Brussels sometime after the war wearing his jacket. It was commonplace for Jewish homes to be looted and heirlooms ransacked during the war – pieces of art, silver candlesticks, ritual spice boxes. Eddie was confident the jacket was his, a conviction substantiated by his perfect recollection of each detail: the cuffs deliberately designed for cycling and the label stitched inside locating the tailor in Leipzig, Germany, Eddie’s hometown. He confronted the man who became defensive and disavowed the accusation that the jacket was stolen. Disturbed by his own flawless recollection, Eddie reported and pursued the man “who could not even read the German label” until he shamefully returned his jacket. The triumphant squeal that followed this story always distracted me from its darkness.

In a logical equation measuring out joy against sorrow, Eddie converted his unfathomable traumatic past into an equally unfathomable, optimistic message for our futures. It was as if he could visualise his pain as finite matter, balancing in determinative scales opposite his greatest joys: his life love Flore, their children and their children’s children.

A bookstore patron who stumbles across Eddie’s autobiography titled “The Happiest Man on Earth” might decide that such a claim seems kitsch, exaggerated or clichéd. But in truth, it is the most accurate reflection of Eddie’s commitment to convert his deepest and most personal anguish into a lesson of universal love.

Losing Eddie during lockdown meant over 100 days apart and without a meaningful goodbye. When I think about what I would have liked to say to Eddie, I am reminded of all the times he tried to prepare me for this moment and how each time I rejected those suggestions, stubborn in my belief that Eddie would live forever. When I think about what he would say to me, I am reminded of the time Eddie looked into the lens of my camera and said, “You will remember me. In a few years, when I will not be here anymore, and for the rest of your life. I will speak to you from time to time, and in your sleep, you will remember me, and I will only say good things.”

Baruch dayan ha’emet. May his memory be for a blessing.