Over the last year, one of pop culture’s favorite topics has been goblins. Yes, you read that correctly, goblins. In early 2022, comedian Jon Stewart went viral for rehashing the decades-old question, “Are the goblins from ‘Harry Potter’ antisemitic?” on his podcast. Then, he went viral again for pushing back against media coverage of his podcast segment, stating that he did not say the Gringotts goblins or J.K. Rowling are antisemitic and the conversation was merely “light-hearted.” Ok, Jon.

Then again, goblins made the news in early 2023 when a new Harry Potter video game called “Hogwarts Legacy” debuted. Though J.K. Rowling had nothing to do with the creation of the game, it has been rightfully criticized for its terribly thought-out transgender character and the fact that the main narrative is centered on a goblin rebellion in Wizarding World during the 1890s.

Throughout these conversations, many have pointed to the fact that it’s not just the goblins in “Harry Potter” that lean on antisemitic tropes — but an issue with the way goblins have been coded throughout history, especially in folklore and literature.

So, are goblins antisemitic?

Ask and ye shall receive, Hey Alma pals and pop culture aficionados alike. From the site that brought you an antisemitic history of witches and an antisemitic history of vampires, it is unfortunately time to bring you a brief explanation of the antisemitic history of goblins.

Let’s go!

First of all, what actually are goblins?

According to Merriam-Webster Dictionary, a goblin is “an ugly or grotesque sprite that is usually mischievous and sometimes evil and malicious.” Though there are goblin-like creatures across cultural folklore, the term “goblin” comes from Europe, with the etymology of the word coming from the Anglo-Norman “Gobelin” or Old French “Gobelin,” and goblin lore dating back to the 14th century.

There is no uniform consensus across Western culture as to what defines a goblin. But on a basic level, goblins were used as a term by medieval peoples to describe a specific species of fairy that is small, thieving, sometimes beast-like and shapeshifting, and either commits pranks or is more murderous. At the same time, they also used “goblin” as an umbrella term for fairytale creatures like the German kobold, Welsh Colbynau, redcaps, knockers (you’ll want to remember this one), trolls and so on.

OK great. And this relates to Jews how?

At the same time that goblin folklore was emerging in medieval Europe, common antisemitic stereotypes and myths like blood libel, deicide, Jews’ association with money and what Jews looked like were also beginning to form. Beyond the violence and displacement this would cause for European Jewish communities in the Middle Ages, antisemitism also had the effect of spawning art.

As laid out by Debra Higgs Strickland in “Saracens, Demons, and Jews: Making Monsters in Medieval Art,” by the 12th century, the stereotypical Jewish “look” was established. In primarily woodcuts and drawings, Jews were often portrayed as having an oversized and crooked nose and either appeared to be demon-like or consorting with the devil himself. This was done with the aim of making Jews easily identifiable as well as seeming as ugly, grotesque, subhuman and evil so Christians would not want to associate with them.

For example, here is a Judensau (literally translating to Jews’ sow, Judensau is a medieval German genre of art which depicts Jews committing obscene acts with pigs) wood print from around 1470:

Now compare that antisemitic image to this Dutch etching of a man speaking with devils in the forms of animals, goblins and hobgoblins from 1682:

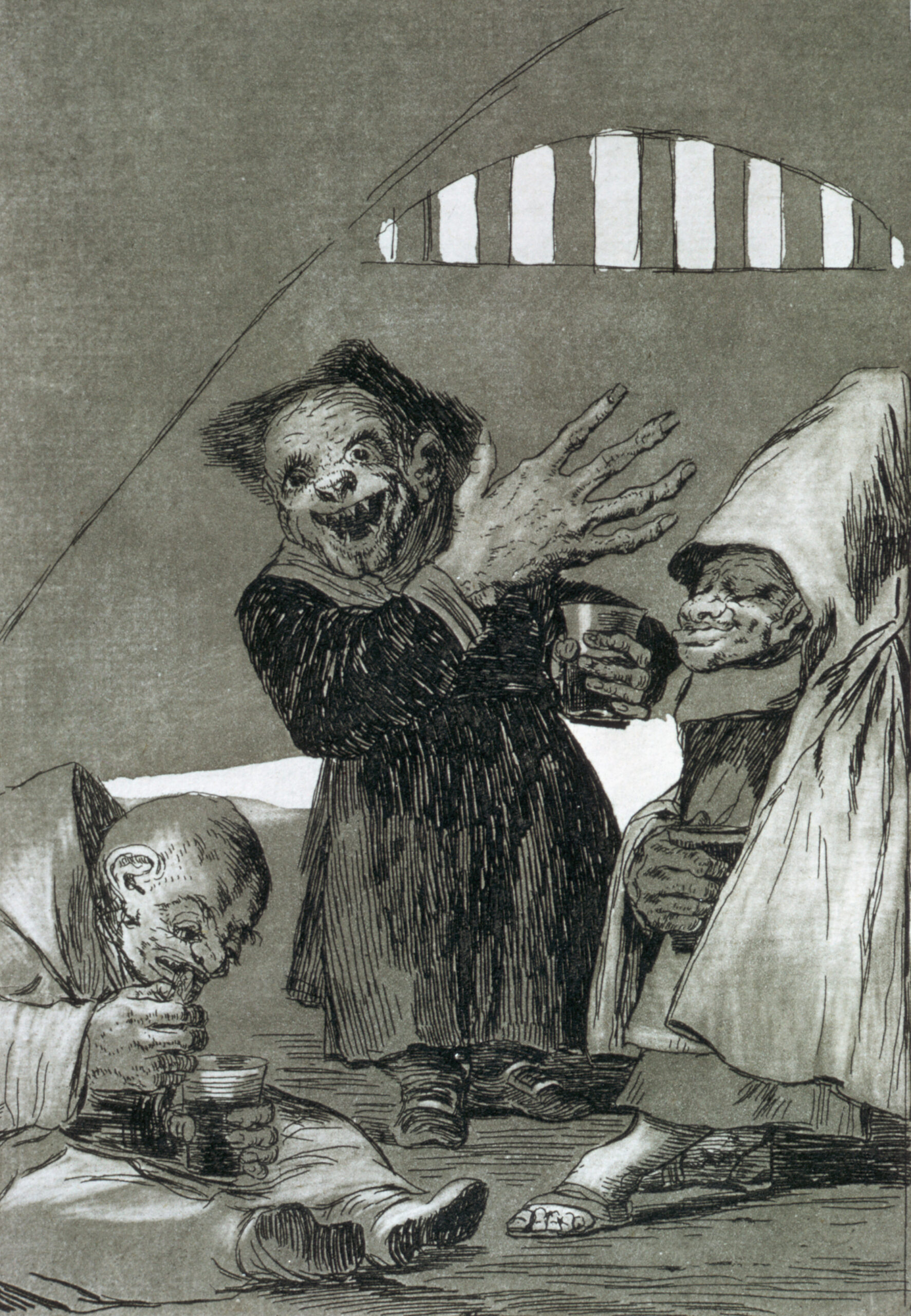

Or this sketch of hobgoblins by Francisco de Goya from around 1799:

Or this scene of a Charles Dickens’ 19th century story “The Goblins Who Stole a Sexton”:

Though the latter illustrations are from a later period and the comparison is not one-to-one, my point is that throughout history, European artists have depicted both Jews and goblins as being ugly, grotesque and monstrous.

Did antisemitism directly affect the creation of goblins?

Yes and no.

I haven’t come across historical evidence which directly states that goblin folklore was influenced by medieval antisemitism or perceptions of Jews, or vice versa. Except, of course, in the case of knockers.

In the folklore of Cornwall and Devon in England, knockers (also known as knackers or tommyknockers) are goblin or gnome-like creatures who live underground in mines and are essentially harmless. They are also, apparently, the ghosts of dead Jews. In 1851, author Charles Kingsley described knockers in his novel “Yeast” by writing, “They are the ghosts, the miners hold, of the old Jews, sir, that crucified our Lord, and were sent for slaves by the Roman emperors to work the mines, and we find their old smelting houses, which we call Jews’ houses and their blocks of tin, at the bottom of great bogs, which we call Jews’ tin…” Additionally, according to Oxford Reference, knockers cannot stand the sight of the cross.

Also, this is an interpretation of what they look like:

Knockers, the Cornish mine goblins, are the most blue-collar fairies imaginable. They're working-class miners who are appeased through offerings of meat pies. #fairy #goblin

(image by Marc Potts) pic.twitter.com/VPuTFgj9jw— Bevan Thomas (@bthomasa) December 4, 2021

So, in summary, knockers are subhuman creatures with Jewish origins that perpetuate the myth that Jews killed Jesus.

So… are goblins antisemitic or not?

Knocker are certainly antisemitic, and though I am not a historian, I do think goblins as a whole do seem to have dubious origins. But whether goblins in contemporary culture are antisemitic, in my opinion, depends on context.

Looking towards the most prominent example of this, the Gringotts goblins from “Harry Potter” are very clearly rooted in antisemitic stereotypes — regardless of whether that was JK Rowling’s intent or not. As literary agent Connor Goldsmith told Hey Alma in 2019, “Rowling’s goblins are nakedly anti-Semitic caricatures — a race of gnarled, hook-nosed misers obsessed with gold, who believe they own everything they’ve ever produced and wizards who purchase things only ‘rent’ from them. They appear to run the entire wizarding economy, and trust no one but their own kind. It’s suggested that secret cabals of goblins work to undermine the wizard government.”

The new “Hogwarts Legacy” video game (which, once again, JK Rowling did not play a part in creating) only reinforces the caricature. For players, the main thrust of the game is to help put down a goblin rebellion in 1890, which is being led by a goblin named Ranrok. According to GameRant, here’s what Ranrok’s goal is: “The main scheme of the primary antagonist is to kidnap the player character, and harvest their blood for a spell that will wipe out his enemies while aligned with a number of dark wizards.” Harvesting the blood of a teenage (essentially, a child) wizard? Sounds a whole lot like blood libel to me.

This caricature is then heightened by other details in the game. For example, this “goblin artefact” in the game bears a striking resemblance to a shofar:

HOLY SHIT THE ANTISEMITIC CARICATURE GOBLINS IN HOGWARTS LEGACY EVEN HAVE A SHOFAR ARE YOU KIDDING ME. ARE YOU JOKING. WHAT THE HELL pic.twitter.com/frZEr6mLkS

— ⬅️ slap it! it jiggles (@chromedupcheeks) February 9, 2023

Additionally, this trophy players win for slaying goblins looks hauntingly similar to Nazi propaganda:

Trophy for killing the goblin in Hogwarts Legacy and Nazi Propaganda pic.twitter.com/oZHqU2nKCA

— ✨ Britney Spear Platform Jubilee ✨ (@MadelineHorwat1) February 20, 2023

Thus far, the best example I can muster of goblins that aren’t antisemitic is from the beloved Jewish children’s book “Hershel and the Hanukkah Goblins.” Ironically, the goblins in the story haunt the synagogue of Ostropol, blow out menorah candles and destroy latkes and dreidels. While sharing the name of “goblin” and indeed looking monstrous, the Hanukkah goblins are in direct opposition to the Jewish community of Ostropol and the Jewish main character, Hershel. They are also not looking to steal the blood of children, they are not money obsessed, nor do they have a secret cabal. They’re just silly mythical creatures that, importantly, are part of a Jewish book written by a Jewish author.

UGH. Are there any folktale creatures that aren’t rooted in antisemitism?!

At least we have Shrek?