Before reading True Believer, Abraham Riesman’s new biography of Marvel comics legend Stan Lee, my knowledge of Stan was limited to “the old guy that appears in the Marvel movies I take my little brother to.” I vaguely knew who he was, but after True Believer, I feel like I understand him — flaws and all.

As Riesman writes, “Stan Lee’s story is where objective truth goes to die.” Lee, born Stanley Martin Lieber in 1922, was a master of creating legends about himself. He told so many stories — so many false stories — over and over again that he eventually believed them to be true. Riesman does a great job of unpacking these myths and half-truths, speaking to many people in Lee’s orbit.

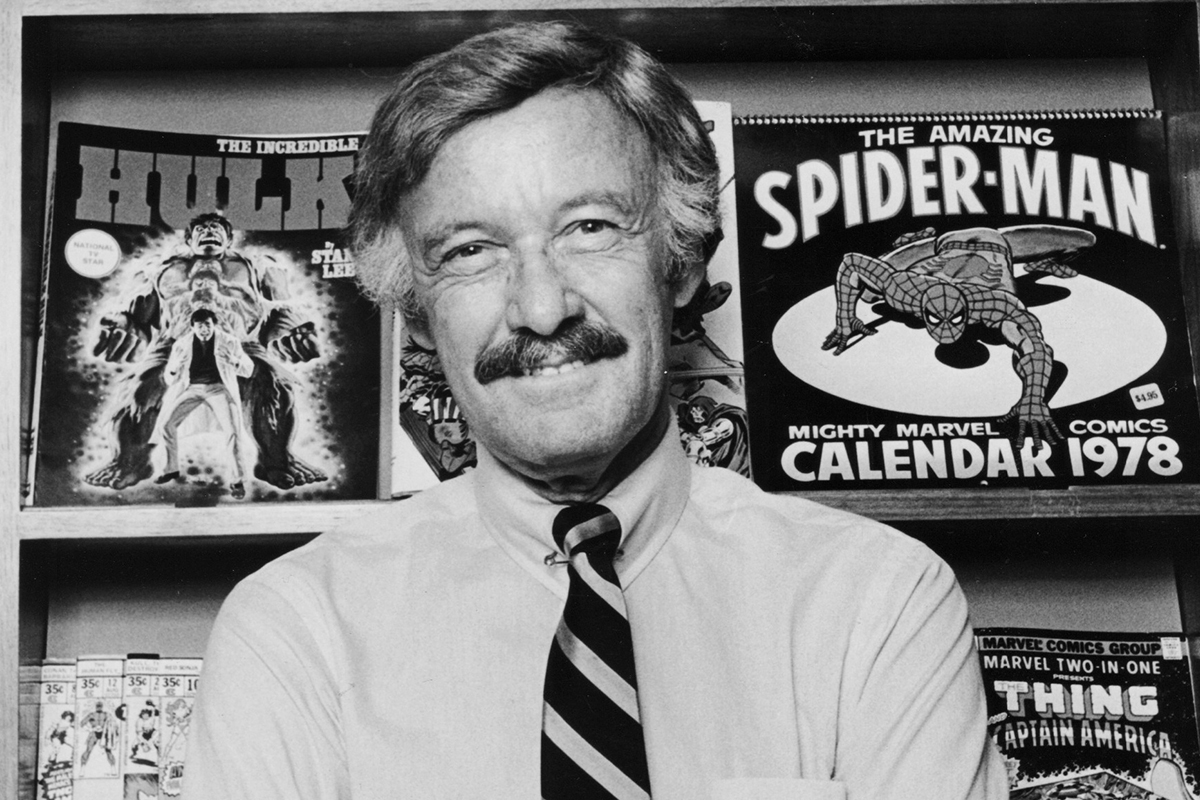

Lee was the head editor of Marvel during a time of unprecedented creativity (Spider-Man, Black Panther, the Avengers, Thor, and more all launched under his tenure), but he spent the rest of his life chasing fame and fortune that eluded him — until the movies started coming out, and his cameos in those films gave him a second wind of fame. And while Stan Lee was born to a Jewish family that fled antisemitism, he resisted identifying as Jewish or claiming any semblance of Jewishness.

Ahead of the publication of True Believer: The Rise and Fall of Stan Lee, I chatted with Riesman over the phone about all things Stan Lee and his complicated relationship to Jewishness — and how Riesman found questions about his own Jewish identity reflected back in the life of this comics giant.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Let’s start with Stan Lee’s relationship to Jewishness. You write that he would walk away from Judaism and the institutions of Jewish life, and Jewishness as a concept, but his parents’ and grandparents’ experience must have been an influence. How do you see this influence, in his work and his life?

You can definitely overdo the degree to which you estimate that Jewishness impacted the stories that he was working on, but I think you really can’t overestimate — or at least should try to be honest about — how much his Jewishness influenced his life, the relationships he had, and the personality that he created for himself.

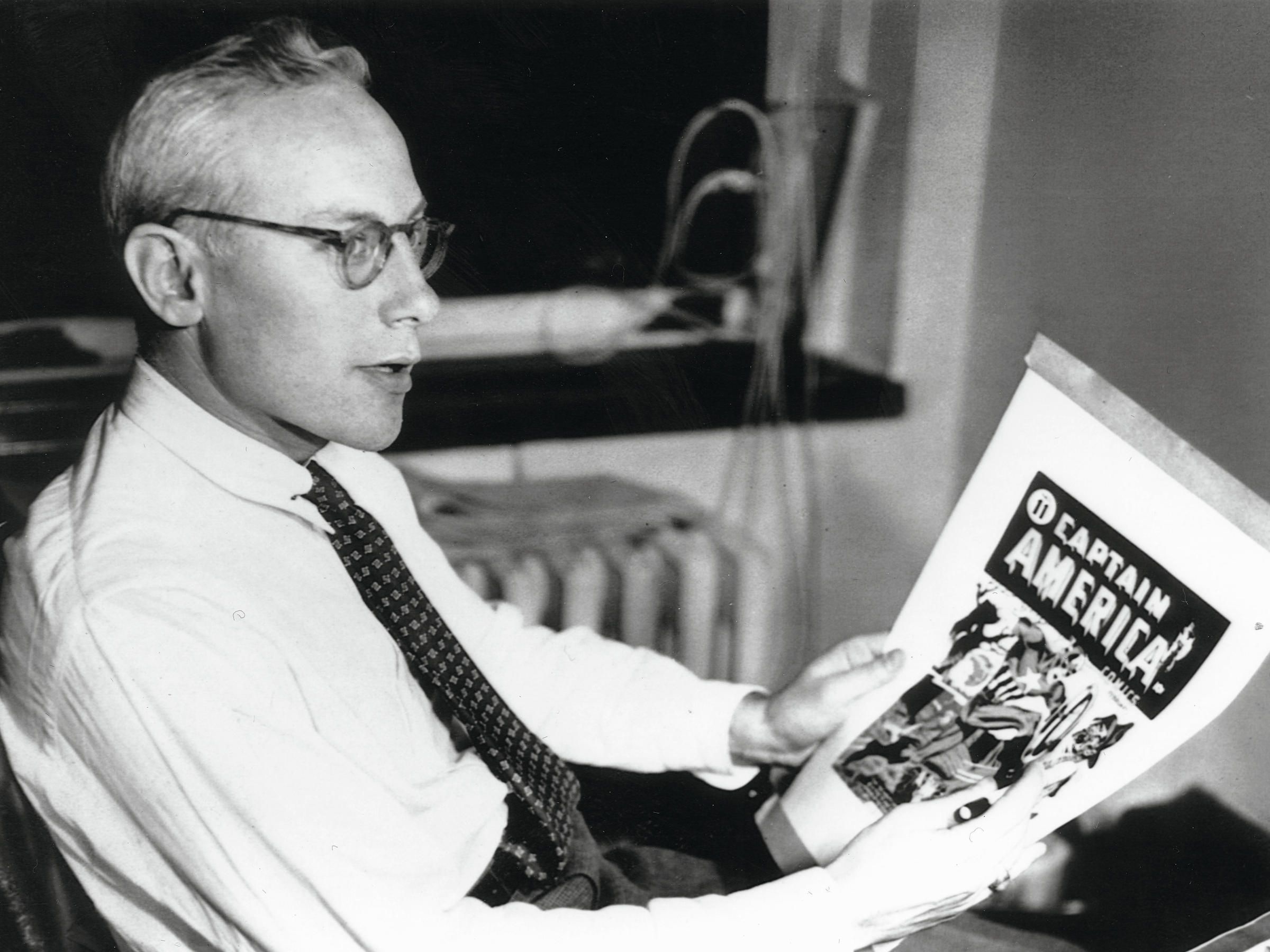

I can’t do too much armchair psychology, but the sense I get is that his father, Jack Lieber, who was born Iancu Urn Liber in Eastern Romania, was a guy who was very passionate about being Jewish. And a lot of that, one assumes, stems from the fact that he was the victim of uniquely horrible antisemitism in Romania, in the latter part of the 19th and into the 20th century. Jack was a hard guy, by all accounts — he was a difficult man to get close to, and could be very harsh and judgmental. He was judgmental about Stan’s lack of relationship to the Jewish people, Jewish institutions, Jewish life. When Stan got successful, he would get these letters from his dad saying, “You’re not doing enough for the Jewish people. You’re not supporting the State of Israel. You have this fame and money, and you’re not pointing in that direction.” Stan never even acknowledged it — the only way I know was from hearing it from his brother. It really tells you about the strange relationship he had with his dad, and the strange relationship he had with his heritage and his ethnic background.

I’m reasonably certain a lot of Stan’s personality — the character of Stan Lee that he came to embody — came out of a rejection of the kind of approach to life and demeanor that his father Jack had. Where Jack was a stern, quiet, and ethnically proud man, and ethnically particularistic in his choice to really emphasize the Jewishness, Stan was somebody who wanted to be jovial, comical, light-hearted, and perhaps what’s most important, beloved by everyone. In no aspect of Stan’s public persona did he emphasize his Jewishness. If you asked him about it, he might acknowledge it.

In the book, you write about interviewing Stan over email and asking him about New York Jewish culture and he completely ignored the Jewish part in replying to you.

He completely ignored the Jewish part! It was as if the word didn’t appear. I can’t exactly place why he was so skittish about Jewishness. But I can’t help but imagine that a lot of it had to do with him trying to escape his circumstances, and to a certain extent, his family. It’s a bit of a chicken and egg thing: I don’t know whether the Jewishness preceded him wanting to get away from that or postdates it, but it’s all part of the piece, which was he wanted to get away from the station he’d been born into.

I love the line, ”He was another ambitious second-generation American Jew who wasn’t afraid to cut corners and do a little backstabbing… If you were to invent him as a fictional character, you might be accused of mild antisemitism.” Can you expand on this?

I wasn’t talking about Stan for that, I was talking about Martin Goodman [the comics publisher who launched the company that would become Marvel Comics]!

Oh my gosh, I fully misread that line.

No, it’s fine — the reason you misread it is that those are traits that Stan would sometimes engage in. There’s a lot of characters in the book, and a lot of them are Jews who make questionable business decisions. I’m not going to name names, but there are a lot of characters in there who fall into the rubric of people who happen to be Jewish, who also had dishonest business dealings. And it’s hard to write about that stuff, because you don’t want to be an antisemite. None of that is because they were Jews.

That said, in Jewish immigrant communities, especially in the early 20th century, you often had a lot of nepotism, looking out for your own, and doing what you had to do in a cutthroat business environment. It was a delicate thing to try and deal with. But there are a lot of people in this story who, if you’re not careful in describing them, you might come across as being something of an antisemite while describing them accurately.

I also feel that way about the idea of Jews “running” the comics industry — that can veer into antisemitism, too, if you’re not careful.

Totally! It can turn into antisemitism, but again, it’s like, “Jews control the comics industry?” Well, they did. That’s not a conspiracy theory. A large portion of these publishing houses were run by Jews, and a lot of the creatives were Jewish. You want to be careful about that, but also you have to be honest in acknowledging the impact that the Jewish experience — if we can generalize and name such a thing — had on the Jews who ended up building this massively consequential industry.

How do you view the relationship between Jews and comics in general?

It’s a very complicated question to answer because it’s changed a lot over the course of the almost 90-ish years of the existence of the American comic book, as a product, and about 80-plus years of the superhero fiction genre. These days, in cultural criticism that deals with Jewishness, you end up with a lot of going, “This person was Jewish, therefore, the art they made was Jewish,” or, “The industry they built was Jewish.” And you can go too far in that direction and end up being a chauvinist and saying, “Well, this person is one of ours. So the things they made also are ours.” I don’t think it’s as simple as that.

I mean, Stan’s a perfect example. Here’s this guy who was Jewish, came from a very Jewish background, and a lot of that informed how his career went. But then when he’s sitting down to actually make comics, it’s unclear how much of the comics are really being made [by him], period. But you can look for “Jewish themes” in those comics and come up with stuff that I guess is Jewish, but it’s also pretty universal. You see people saying, “Marvel was Jewish because it has Spider-Man who’s very neurotic and lives in Queens.” And it’s like, a lot of neurotic people lived in Queens of any number of ethnicities, it’s a very diverse borough, that does not necessarily narrow it down to Spider-Man being Jewish. I love that they had a Jewish Spider-Man in Into the Spider-Verse, I thought that was a delightful little touch. But I don’t think you can say, “Well, you go back to the original comics and this is a fundamentally Jewish character, a fundamentally Jewish story.” It’s a story about an outsider and a nerd, who ends up having a lot of power and responsibility, etc. That can be universal, that can really apply to any ethnic category.

I’d apply that more broadly: It’s hard to identify exactly what is Jewish in a comic book and what isn’t. I get nervous when people try to claim superhero fiction, and the comic book industry, for the Jews. I just don’t think it’s as simple as that.

What is really interesting is that in Jewish media, or among Jewish communities, we’re very quick to claim Stan as Jewish even though Stan probably wouldn’t have accepted that in the way that we understand Jewish celebrities today.

He really wouldn’t have. And that’s not a diss, necessarily, it’s just he had a different relationship to the concept of being Jewish then I do, or any number of other people do. But he has overlap with a lot of people who do come from a Jewish background. There are a lot of folks out there, there are more every day, who are aware that they come from two Jewish parents, with Jewish parents going back countless centuries before that, and they have decided this isn’t my thing. And they don’t want to be a part of it. There’s a lot of panic that happens in the Jewish community when people try to consider that — it sounds like we’re going extinct, and what do we do about it? I don’t like giving into panic.

As far as your career as a writer and journalist, how has your Jewish identity impacted your work? The answer could also be like, it hasn’t.

No, it really has. I had an idiosyncratic upbringing in some ways. I’m patrilineally Jewish, but I was raised Jewish in this suburban Illinois Reform Jewish context. I was not coming up in a world where I saw things primarily through a Jewish lens. I did not think too hard about my Jewishness, or wrestle with it in any big way, prior to the Trump presidency. Once Trump got elected, various things in the air clicked, and all of a sudden, I went, “Oh, I have to actually think about what it means to be Jewish. And what the responsibilities are for that.”

Being a journalist, the way I process things is usually, if I really like something, or I find something really interesting, I try to write about it, because that’s the easiest way for me to really formulate my thoughts in a meaningful way. Starting in late 2017, early 2018, I started actually writing about the Jewish world. And I’m very lucky that where I was working at the time, New York Magazine, was willing to take a chance and let me write about that stuff. Because it’s off their beaten path. It’s become something that I’m very lucky to say: I’m allowed to write about it a fair amount for various outlets. The questions of Jewish identity, Jewish responsibility, and Jewish history are things that really haunt and energize me at the same time. I can’t not think about that stuff at this point.

I was somewhat lucky that this book ended up having all these Jewish components to it. The initial article I wrote about Stan, which came out in 2016, didn’t really have anything Jewish in it, because I wasn’t really in that mindset at the time. But by the time the thread got picked up again, when Stan passed away in late 2018, I was like, there’s this whole aspect of his story that I know nothing about, that nobody even really talks about in any kind of way. His story is something I think about a lot in context of my own story — there’s a lot of differences, but one big thing is this question of, well, you know, that gets a little too grim, I don’t want to get into it.

It’s okay! This can get grim.

I think a lot about Stan’s status as “the last Jew of his line.” He had a child, who is still around, who is totally non-Jewish, it’s just not part of her identity in the slightest. And Stan was the last Jew of those streams that all culminated in him, the same way that I am if I don’t have kids, which is sort of a big question mark for everybody in the world, and especially in the United States, right now. If I don’t have kids, maybe I’m the last Jew in my line. And that’s something that’s very sad to think about. The way I frame it in my head is: The last chapter of a story is oftentimes just as important as any other chapter, if not somewhat more so because you have to stick the landing. And just because you’re the last chapter doesn’t mean you’re not part of the story. I try to foster Jewish identity and thought and community in every way I can, but if I don’t end up having a big den of Jewish kids, am I doing something wrong? Have I screwed up? Is this me forsaking my ancestors? This is something that I think about a fair amount.

And it’s something I thought about a lot in the context of Stan, because he did not really care about being a Jew, but he was a Jew. And I do care about it. The stories of our families have gone on for millennia, and then we have to decide what we do with that responsibility.

I was really interested to learn about how Stan’s cameos in the Marvel films — which was honestly my only knowledge of Stan Lee before reading this book — reshaped his image and gave him this legacy, whereas you sort of argue that shouldn’t necessarily be our lasting image of Stan.

It’s complicated. I’m not trying to say Stan was more saint or more sinner, or have final judgment on him. There are a few morals of the book, I would hope, and one of them is: There are no superheroes. It sounds so simple but humans, especially Americans, have to be reminded over and over and over again that celebrities are not different. Celebrities are not another species. Celebrities have not been granted superpowers. Celebrities are people, they’re people who happen to have become famous. Sure, there are things that people do or say, or aspects of people’s personalities, that can be deeply inspiring and that can advance humanity. But we really start to run the risk of losing our grip — well, we’ve already all lost our grasp on reality — but we run the risk of further losing our grasp on reality if we continue to indulge in this celebrity culture that makes the people we like out to be something they aren’t. That only leads to disappointment and backlash and misunderstanding and misrepresentation.

The other moral the book is that you have to sit with ambiguity — moral ambiguity, factual ambiguity, narrative ambiguity. We want to believe that there are definitive answers to everything. And I’m sure on some objective level, there are answers to everything, but we don’t live with that objective level. We’re not Hashem, we’re not looking at the world from the outside, we’re in it.

When it comes to the cameos, they really did create this very sanitized version of a human being that is Stan Lee. That’s not a crime! It’s been done with plenty of people. It’s dangerous to turn your love of those movies and your love of his cameos into a gross misunderstanding of who he was, and the nuances of what he did and said.

The cameos are massively consequential for his career. You really have these two bursts of fame for him: One in the ’60s, when the comics initially become popular, and then one in the new millennium, when he starts doing the cameos. The cameos would have been impossible without the comic stuff. But the cameos, I would argue, are a bigger deal for his brand and legacy. There are plenty of people who were important in the ’60s who are never really on our radars, but Stan’s stock was bumped up again and became more valuable than it ever had been. I would caution people to not assume that the Stan who appears for a couple of minutes in every one of these movies is the Stan Lee, the Stanley Martin Lieber, the person who actually walked this earth. You’re watching a character, and it’s a character that he created and created very deftly, and a character that has had a lot of staying power and has meant a lot to a lot of people — which is something I really respect. But it’s still a character. It’s not who he was.

My last question is, in your research and in your time spent with Stan Lee over the course of this book, what was the most surprising thing you learned?

Honestly, and I’m not just saying this cause I’m talking to you at a Jewish outlet now, the thing I most remember being shaken by was learning from Stan’s brother Larry Lieber about the letters that Jack Lieber used to send both of them, but especially Stan, in Jack’s later years. For reasons I can’t quite articulate, that really resonated with me. I was really surprised at how much I could relate to Stan’s struggle with Jewishness, which was something no one had even talked about. It was surprising to not only find out that that struggle, and those questions, were there, but that there were struggles and questions that I could see a lot of myself in.