“You know,” shouted a group of men at me from across a darkened parking lot, “we still like girls with short hair.” It was late out and there were barely any lights on, so I could only just make out their faces. I was exhausted from working an eight-hour retail shift, during the holidays, in the middle of a pandemic, so I wasn’t sure if they were the same men I had rung up at the cash register earlier. But I couldn’t help but think that they were.

Had they been waiting for me to leave work?

Earlier that day I had been cornered and solicitously asked what time my shift ended. Eventually when I ran out of plausible non-answers and it became clear that I wasn’t going to tell them my schedule, my manager had to intervene. While sitting in the musty, dimly lit break room, as the store’s muffled playlist droned in the background, I shrugged off the interaction and decided to just get through the next hour of work.

So, the group of men clustered by the entrance to the mall parking lot felt a little too coincidental.

I wish I told them to fuck off. I wish I had stopped walking and asked them why they thought I cared that they liked “girls with short hair.” I wish I told them just how pathetic they were to follow me. I wish I had said something, anything, in response.

Instead, I said nothing and lengthened my strides until I was practically jogging by the time I reached the safety of my car.

It was only after I pulled out of the parking lot onto a familiar street that I began to feel anything other than all-consuming fear. My shaking hands were no longer wholly a symptom of the sharp sudden panic that had gripped me from that first shouted word, but were now from a new feeling entirely: anger.

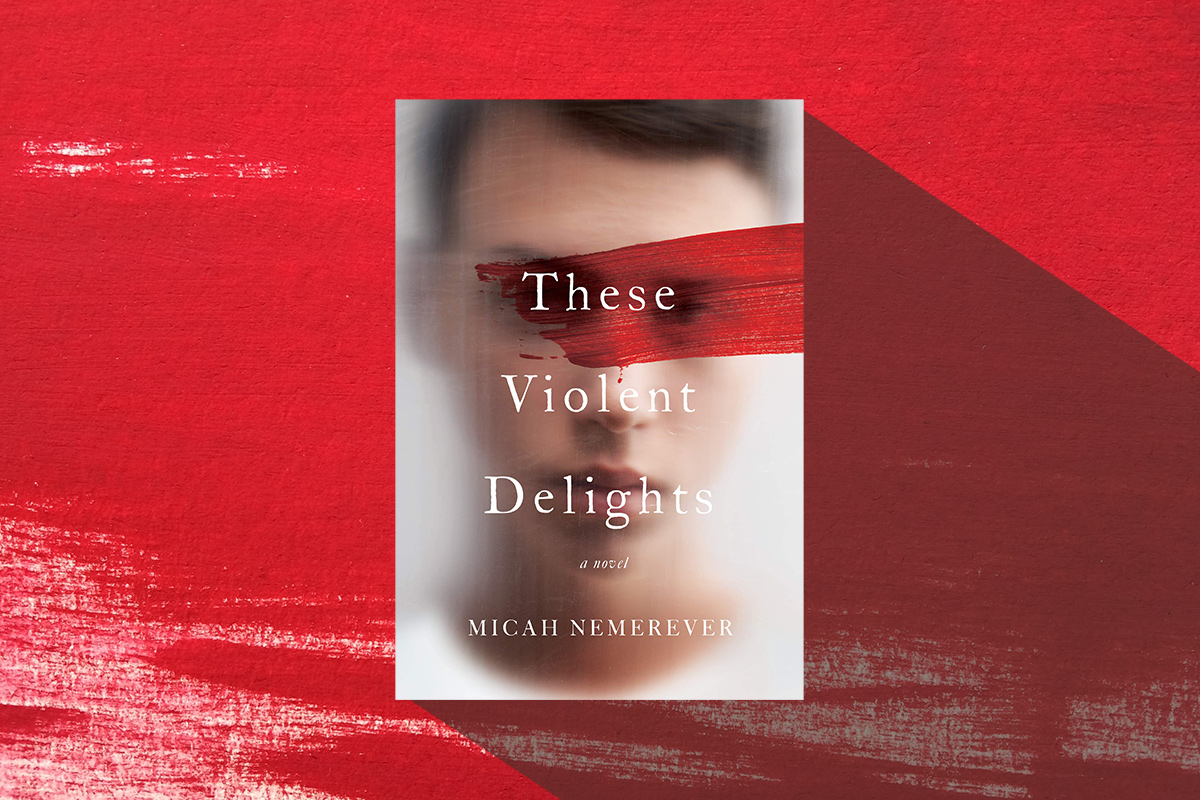

The surge of emotions that accompanied this experience reminded me of how I felt while reading Micah Nemerever’s debut novel, “The Violent Delights.” When I initially began reading it back in October, I almost immediately had to take a break, so strong were the feelings evoked by reading about characters whose internal emotional landscapes were all I feared I might become.

Early on in the novel, one protagonist’s mother acknowledges her repressed anger. “’You might not believe me, but I get angry, I do, I get terribly angry that people can’t understand. But there are limits,’ she desperately warns her son, ‘to what you can expect people to understand without living it, and that’s not something they’re doing to you. You can’t fight everybody all the time, you still have to live with them—’”

“‘Hell if I do.’ His voice nearly broke, but he didn’t dare let himself fall silent lest the weakness reach his face. ‘I’m done trying. Dad tried, he spent his whole life trying, and I refuse to end up the way he did.’”

Nemerever’s novel depicts the developing romance between Paul and Julian, whose mutual obsession and self-delusion eventually results in a shocking act of violence and ensuing moral crisis. Resting at the intersection of gay desire, dark academia and ethical dilemmas, “These Violent Delights” evokes a particular sense of Jewish queerness I have never before read.

Set in 1973 Pittsburgh, one generation removed from the Holocaust, this novel is profoundly Jewish. The novel’s time period and location are no coincidence: 1970s Pittsburgh was a time of uncomfortable in-between moments for Jewish American identity, with the collapse of the steel industry signaling a decline in Pittsburgh’s working-class Jewish association.

The protagonists meet in a psychology class as first years in college, when Paul impassionately argues about the ethical issues embedded within the Milgram experiment, a series of controversial experiments interested in explaining the role of authority in shaping obedience, to the mocking entertainment of his classmates. Only Julian, whose turbulent bitterness compliments Paul’s ever-simmering rage, sees something in Julian’s moral argument. After all, the experiment’s preoccupation with the role of power and obedience to authority would stand out to Paul, whose father was a refugee from the Holocaust, and Julian, whose family continuously tries to pass as WASPs rather than acknowledge their Jewish identity.

From there, Paul and Julian grow increasingly enmeshed and together they channel their self-conscious intellect and vulnerability into a commitment to enact planned violence together.

Throughout “These Violent Delights,” Nemerever skillfully uses historical fiction as a lens through which he processes the present. Drifting out of the idealism of the ‘60s, Watergate and the sudden influx of political assassinations produced a generation shaped by cynicism. This is an experience not unlike coming of age during the mid-aughts, a decade defined by a similar sense of disillusionment spawned by senseless violence and political corruption.

Like many who grew up in an era of school shootings, both myself and Nemerever learned to be terrified of the capabilities of adolescent anger. The alienation and loneliness many queer teens experience rarely result in violence, yet, as Nemerever reflects in his author’s note on the particular love queer teens so often experience, “these relationships felt like another latent threat I carried inside me, one that fed off my alienation from the outside world by confirming it.”

Julian and Paul’s violence functions as an exorcism of the seeming boundless possibilities of otherwise unexpressed anger. In pushing their rage at the outside world to the extreme, Nemerever captures a particular internal experience of growing up queer and Jewish in a world hostile to all that those identities represent.

I also took an Intro to Psychology class during college, but unlike Paul and Julian I waited until my sophomore year to enroll. My senior year of high school I had taken Advanced Placement Psychology, with the vague idea that it would guide my eminent college applications — maybe I would apply as a psychology major? And while I’m sure that the Milgram experiment was mentioned at some point, what I can more vividly recall was my teacher calling me a “feminazi” to the muffled giggles of my classmates.

I was shocked, even though it was hardly the first time someone had said something like this to me. You never get used to it. I remember asking, with faux humor injected into my voice, if he realized that he had just called the only Jewish kid in class a feminazi? He neither seemed to care, nor fully comprehend the implications of the word. But by saying it he inscribed the word on me permanently, and as I walked through the school hallways to other classes it followed me. Distinguishing me as other, someone unlike the rest of their community.

This otherness is one embodied within both Julian and Paul: their queerness, their Judaism, their disinterest in performing the stilted dance of the status quo they are thrust into. An otherness that inherently challenges something deep within those that would have unquestionably read about the Milgram experiment, those who would interpret anger as only ever a negative emotion.

Anger is both a necessary and a cathartic expression in responding to the forces that would deny my humanity. It was not anger that pushed those men to harass me and it was not out of anger that my high school teacher called me a feminazi, but rather hatred and the urge to destroy something transgressive.

Paul and Julian’s mistake was not in feeling rage or passion, but rather in their transference and in their expression of those feelings. Still, “These Violent Delights” gives artistic expression to and a forum for queer rage that would otherwise never be safely available.

As I drove home from work that night in December, I felt seized briefly by the boundless possibilities of my own anger. I was furious, but it was too late to do anything — besides live vicariously through these characters who reached the tipping point that so many of us approach, but never cross.