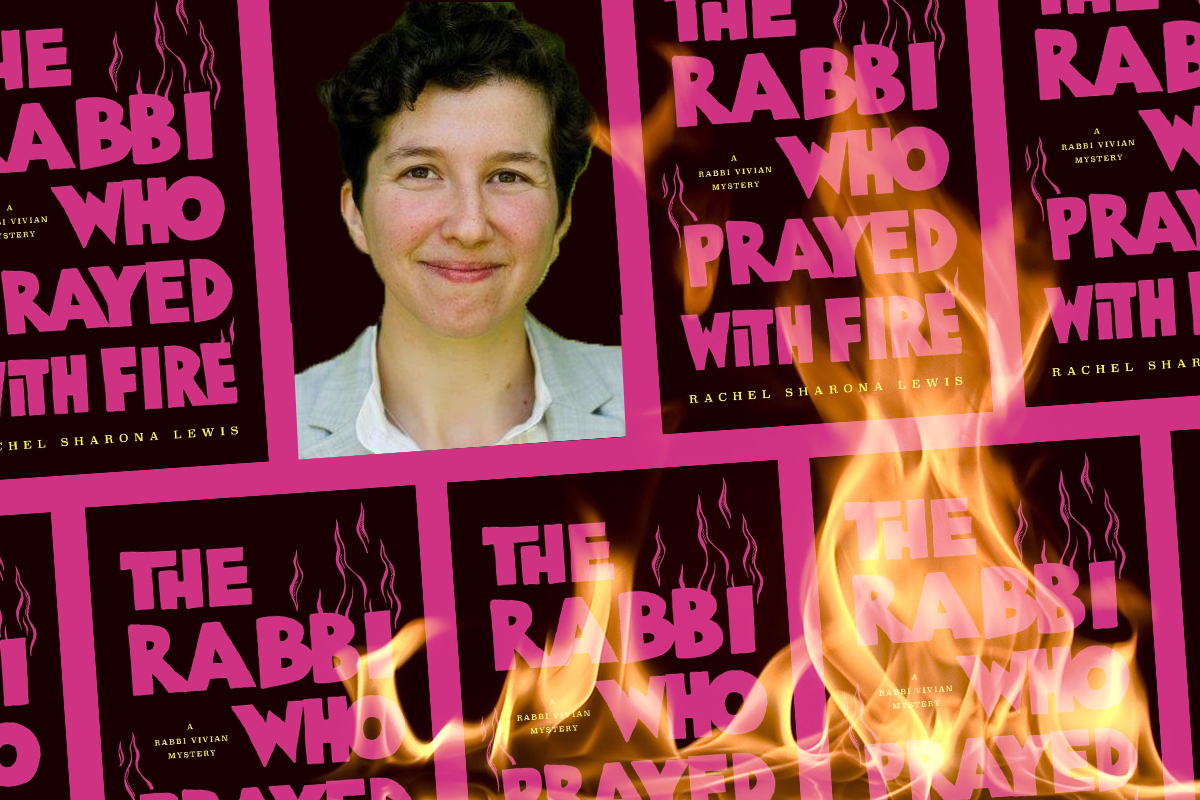

As a queer “wannabe rabbi” living in Providence, Rhode Island, I really feel as though Rachel Sharona Lewis wrote her debut novel, “The Rabbi Who Prayed with Fire,” just for me. The mystery tells the tale of gay Providence rabbi Vivian, whose synagogue catches on fire. Its pages are rife with commentary on things from synagogues’ bureaucratic structures, to police brutality, to the difficulties that come with dating as a queer female rabbi.

I stayed up all night reading this book. I could not get enough of it, laughing at the relatable and cringey moments, absorbed in both the mystery of Congregation Beth Abraham’s fire and what would happen with Rabbi Vivian’s love life.

Recently, Rachel Sharona Lewis sat down with me virtually to talk Jewish communal politics, social justice, and rabbinic dating lives.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

In your bio, you refer to yourself as an “accidental mystery writer.” How did this accident come to be?

I never planned to write fiction. In summer 2017 I stumbled upon a library sale at a small beach town. They dumped thousands and thousands of their books onto the lawn. Very soon into browsing, I discovered a set of Harry Kemelman’s “Rabbi Small” series, which was written in the 1960s, ‘70s and ‘80s. It centers a Conservative rabbi in a fictionalized beach town on the north shore of Massachusetts. He used Talmudic logic to solve murders. It felt like the backdrop was the mystery, and what the author was trying to comment on was the working dynamics of the Jewish community at the time.

As I read, I was struck by how familiar it felt even though it was so long ago, and was excited at the prospect of using the genre of mystery through the lens of a rabbi to comment on today’s Jewish communal dynamics. Scenes started coming to mind that felt really reflective of my own life — I work with synagogues doing social justice organizing and know a lot of rabbis, shul presidents, and young Unitarian Universalist ministers, and have been part of various political campaigns. So I decided to start writing this book. Fiction started pouring out of me. In the past four years when I was writing, there was so much going on in our world that felt really hard. Writing felt like a way to engage my imagination and process, thinking through the kind of world that I was living in and also want to live in.

It means a lot to me for the protagonist to be a queer activist rabbi. What do you think about the kind of representation you created?

The primary tool Rabbi David Small uses to solve murders is pilpul, Talmudic argumentation and discernment. The tools that I wanted Rabbi Vivian to solve the mystery of the shul fire with were pretty different, such as being able to build deep relationships, listen to people, and get to the bottom of things when they feel unjust. That feels very feminist and queer to me.

The book opens with someone dropping the Torah, a very big deal in Jewish law — some traditions require those who witness it to fast for 40 days. This starts the novel off with suspense and sets the synagogue’s political stage as they debate over how to respond. How did you get the idea?

I was present for a “Torah drop” when I was a teenager. It was in the early morning service after Shavuot, where you learn all night. Everybody was very groggy; this was in an Orthodox shul so I was on the women’s side of the mechitza (divider) and didn’t see everything, but there was a huge thud as the Torah was brought to the men’s side. It was so intense; people were silent and didn’t know what to do. That feeling really stuck with me as a very heavy and consequential thing, a very powerful moment. I wanted the beginning of the book to have this feeling of knowing there was suspense but not knowing exactly what was going to come.

It was hilarious reading Rabbi Vivian socially navigate being a rabbi, from her and her clergy friends doing a “swivel check” to look for congregants at the diner, to accidentally introducing herself as “Rabbi Vivian” when asking a crush out. What inspired these moments?

One inspiration is that my wife, who is a Jewish chaplain, lived in Poughkeepsie and had a friend group of ministers and rabbis who all hung out together and had similar experiences. The “swivel” is straight out of their experiences of consistently being in public places and trying to make sure congregants weren’t around so they could let go a little bit. I have also consistently been around rabbis and rabbinic students. Everybody is trying to figure out their lives and dating, what it means to be a leader and member of a community all at once — it’s hard and pretty hilarious at times.

Rabbi Vivian and her clergy friends face misogyny from congregants and colleagues. Do you see this problem in faith communities, despite more communities now ordaining women?

A lot of the misogyny is somewhat subtle. Whenever the president of the congregation, Harry, says “Rabbi,” Vivian knows he is referring to their senior rabbi, Rabbi Joseph. These smaller moments of sexism feel rampant in any part of society regardless of how far we have come. For anyone who is not a cisgender white male, it will consistently feel true. Synagogues are institutions in the same way political bodies are institutions in the same way universities are institutions — they are places where power is wielded. That is often a realm in which there is sexism, and it felt important to demonstrate that.

This novel hit a hot-button issue head on: police brutality harming people of color, while rising antisemitism results in white Jews’ strengthening their relationships with police. How did you feel writing about such a timely topic?

It really evolved. I wrote the first draft in 2018, and shortly later the Tree of Life shooting happened in Pittsburgh. At the time, the storyline about the threat of antisemitic violence was less potent and serious. I knew, as I was rewriting, I needed to take that more seriously. This was happening in my mind and heart — I didn’t think that kind of violence was possible in a shul where I myself might go to for Shabbat.

A similar thing happened in the police brutality storyline. I was close to finished with the book at the beginning of 2020. There’s a storyline where the synagogue custodian, Raymond, and his son, Mac, are dealing with the aftermath of intense police brutality in Providence. I had originally written the end of that storyline as a meeting between Mac and collaborators with the police chief to get seats on a committee that would put together an oversight committee for the police. I realized that was totally not the right ending for that story; things were far worse, and if Mac and Raymond were real people, they would not pursue justice through a meeting to get seats on a council to oversee a committee. I changed that entirely to be a city council hearing on the budget, and the ask was around reallocating funds away from the police to other more important investments in communities of color in the city. There were a lot of twists and turns in response to what was happening around me, and writing this was a way for me to digest what was happening.

How do you suggest Jewish communities begin having these hard conversations?

Where I landed after writing this is that there are no easy answers, but the questions we have to be asking are, “What is the cost of my decision? How does that cost stand up to the values that we claim to have?” It felt important to locate these conversations within the context of individual relationships — choices being made by the synagogue looking towards police for protection and how they were in conflict with the well-being of an important community member, Raymond, and his son. That happens in all our communities; we make decisions impacting people who may not yet be there, and people who are there whom we are not centering.

It was interesting seeing Rabbi Vivian sometimes miss the mark in her relationships with folks of color, despite seeing herself as superior to the white Jews around her. Why did you write her this way?

When I was editing, I had some really helpful feedback from friends who asked why Vivian should have a particular analysis if she hasn’t encountered these situations before, that she needed to do more work. This is true for all of us. I am constantly learning; writing this book was a process of learning for me. I hope this book is an invitation to bring our grappling and mistakes into the conversation.

Beth Abraham, like many synagogues, is struggling with membership and reaching young people. Senior Rabbi Joseph is mourning “the loss of the Jewish tradition,” while Rabbi Vivian complains that Beth Abraham is “out of touch” by not taking action on social justice. What is your advice to Jewish institutions that are trying to reach the next generation?

Most liberal and progressive young Jews I know who want to be part of institutions want both spiritual nourishment and for the community to leverage its resources for good. If you’re an institution in a city that is being gentrified, where there is police brutality against people of color, Black folks in particular, where poor parts of town have higher rates of asthma because that is where the dump is, our institutions can play a role in the goings-on in the city. On the other hand, there is something to be gained in being part of intergenerational community. Being able to swallow some parts of institutional life is also a challenge that younger Jews could take on.

What has the response to your book been like from your Jewish community?

Younger queer Jews love it! You nailed it when you said you feel this book is “for you.” In a lot of cases, Vivian’s specific experiences are really particular to young Jews, queer Jews, and young queer Jews in progressive circles. It makes me really happy that I can mirror people’s experiences. It is also heartening that older people who read the “Rabbi Small” series have reached out and said they love this — that it feels different from the original series, but because of the emotional connections they had to the original books, they had entry into this. That was surprising and lovely, showing an intergenerational dialogue that can happen. Someone reached out to me to do a book club with this book and one of the “Rabbi Small” books. I love that idea.

Can we read more of Rabbi Vivian’s adventures in the future?

Yes! It will probably be a year or two. It has something to do with climate change and robots.