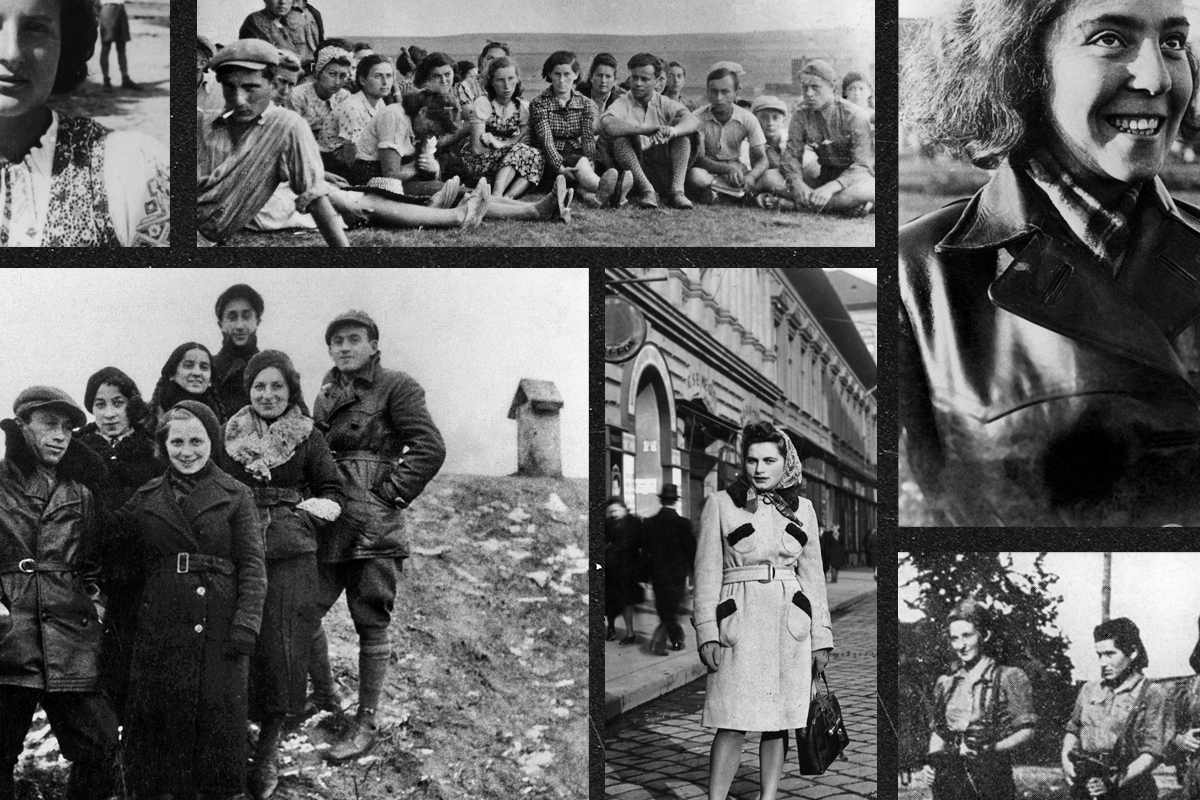

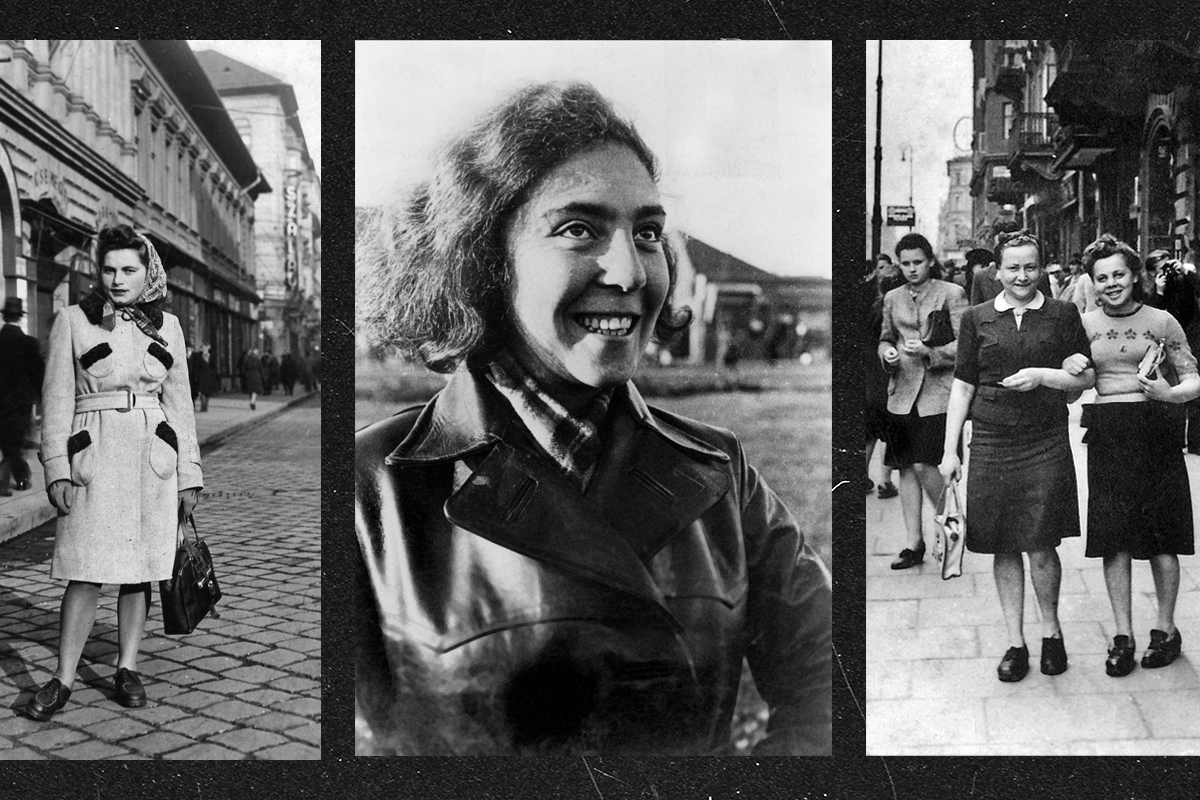

During World War II, armed resistance leader Zivia Lubetkin attacked German soldiers as they attempted to round up residents of the Warsaw Ghetto. Then she led fellow Jews to safety through the city’s sewer system.

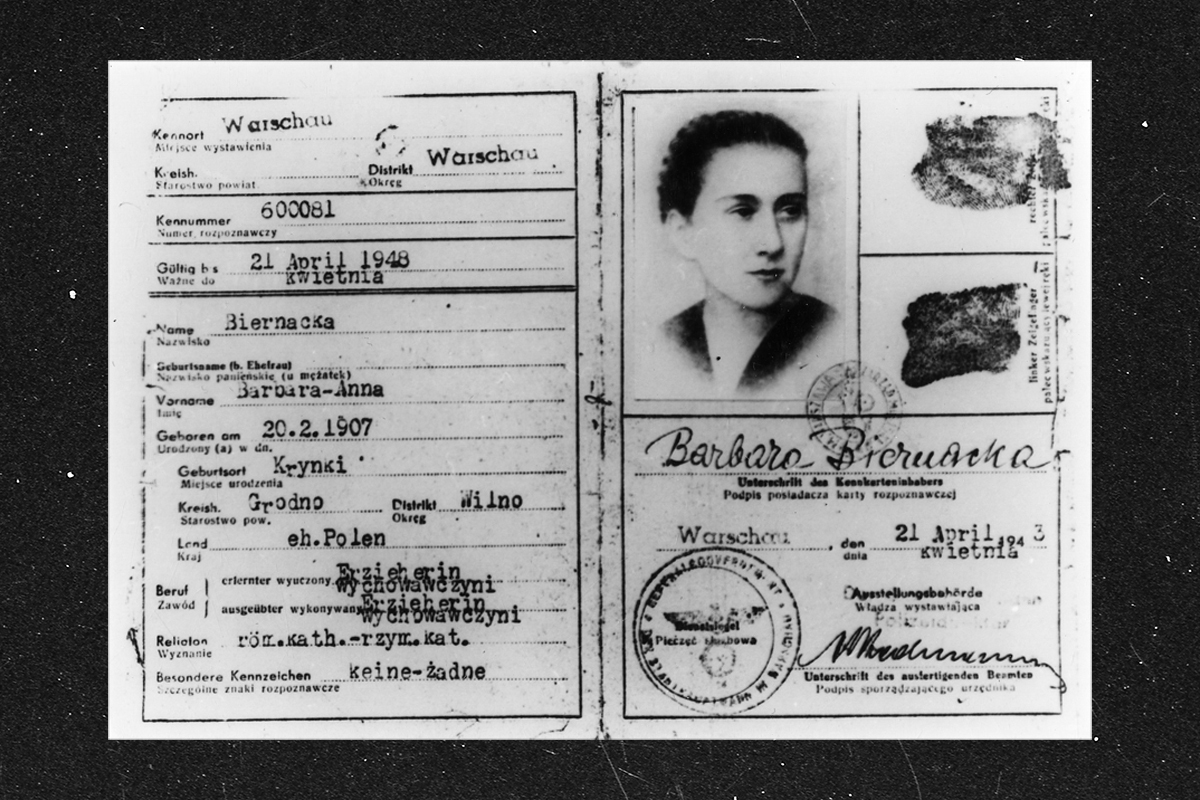

Using forged papers, teenaged courier Renia Kulkielka bought and smuggled stolen weapons, strapping them to her body and hiding them under piles of potatoes. She carried messages, withstood torture, and escaped from prison.

Twenty-three-year-old partisan Vitka Kempner sneaked out of the Jewish ghetto in Nazi-occupied Vilna (Vilnus) to bomb a train full of German soldiers and supplies. Later, she sabotaged the city’s electrical transformers, knocking out the lights.

These missions sound like they were dreamed up by a screenwriter, but they’re all true. Zivia, Renia, and Vitka — and many other women — regularly risked their lives to help fellow Jews in Nazi-occupied Poland. They performed open-air surgery in forests, infiltrated the Gestapo in Grodno, smuggled guns in teddy bears, and assassinated Nazis. Their awe-inspiring and occasionally absurd efforts are chronicled by Judy Batalion in her new book, The Light of Days: The Untold Story of Women Resistance Fighters in Hitler’s Ghettos.

Batalion first encountered these women in 2007. She explained, “I was living in London, and my Jewish identity stood out there in a way it hadn’t on the east coast of North America,” where she was raised.

In her work as both an art historian and a comic, Batalion found herself on the receiving end of comments like, “‘Oh, you should really marry a non-Jew, your children will be better looking’ — this was from a [female] producer I was working for,” Batalion told me. At a work dinner, fellow women academics agreed that Jewish doctors only cared about money. The comments upset, confused, and angered Batalion, and she didn’t know how to respond to them: “I come from a family of Holocaust survivors — was I supposed to run? Face it head on? Joke back?”

Batalion decided she needed a role model, a Jewish woman whose bravery might help her “understand how to handle remarks about my Jewishness and my Jewish looks.” She chose Chana (Hannah) Senesh, the Hungarian-born Jewish paratrooper who was captured and executed during a 1944 British mission to gather intelligence and rescue Hungarian Jews.

She soon headed to the British Library and ordered all the books that mentioned Senesh. (Spoiler alert: There weren’t many. Still, Batalion’s research did inspire Totally Chana Senesh, the one-woman show she’d later perform at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival.)

One of the books Batalion requested “was unusual,” she recalled. “It had a worn, blue cover, and it was musty. It was in Yiddish, in tiny script, about 200 pages.” This was Freuen in di Ghettos, a 1946 compilation of newspaper excerpts, articles, and memorial essays by and about the women of Poland’s Jewish resistance.

To Batalion’s surprise, “it was not a vague Talmudic hagiography, it was a Yiddish thriller. I was blown away.” And so she began researching the women of Freuen in di Ghettos, and writing what would become The Light of Days.

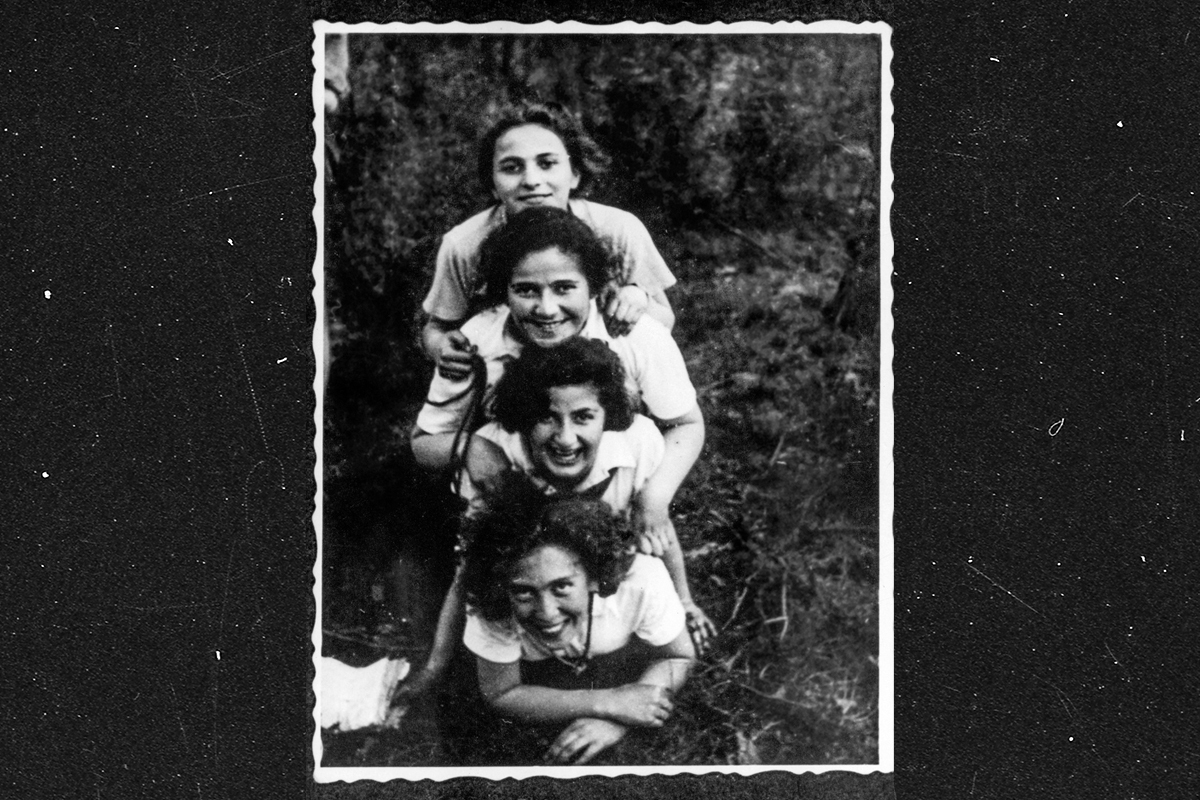

House Museum, Photo Archive

The Light of Days is amply documented; the book’s more than 500 pages are based on memoirs, Yad Vashem testimonies, and contemporary articles, as well as interviews with subjects’ families and scholars. But until now, the women Batalion profiles received scant attention.

Why aren’t these heroines better known? I certainly would have been inspired by Havka Folman and Tema Schneiderman, who smuggled grenades into the Warsaw ghetto via menstrual pads and underwear. Of course, my ignorance isn’t representative, since I’m a Hebrew school dropout with a limited Jewish education. But Batalion is the product of a Jewish day school, fluent in Yiddish and Hebrew (as well as English and French), and the granddaughter of Polish Holocaust survivors.

There are several reasons why the women’s efforts went unheralded for so long, Batalion explains. First of all, the majority of female resistance fighters died during the war, and inevitably some knowledge of their efforts died with them. And of course, “women are routinely dropped from stories in which they played key roles, their experiences blotted out of history,” she points out. In this case, “some women’s writings were censored to fit political motivations, some women faced blatant indifference, and others were treated with disbelief, accused of making it all up.”

Additionally, a number of fighters simply did not want to talk or write about their experiences. Former courier Chasia Bielicka was reluctant to share her story since, compared to survivors who’d been in concentration camps, she felt that she’d “had it easy.”

Finally, in the years following the war, some Israeli politicians portrayed European Jews as “physically weak, naïve, and passive,” in contrast to strong native-born Israelis. Drawing attention to European Jews’ wartime resistance efforts would undermine this stance, Batalion observes.

The narrative of Jewish passivity during the Holocaust is particularly enduring. The belief became firmly established in the early 1960s, according to Richard Middleton-Kaplan, PhD, in Jewish Resistance Against the Nazis. That’s when political theorist Hannah Arendt argued that it was cooperation from Judenrats (local Jewish councils deputized by the Nazis to carry out their orders) that enabled the mass deportation and extermination of Jews, and both Holocaust survivor/psychoanalyst Bruno Bettelheim and Holocaust historian Raul Hilberg claimed that Jews didn’t resist the Nazis. Despite plenty of evidence of Jewish resistance, the idea persists today.

Batalion’s new book could help put these inaccurate and destructive beliefs to rest. With their legacy of heroism, grit, and righteous mayhem, it seems like even after death, Zivia, Renia, Vitka, and their peers continue to fight for Jews.