A few weeks ago, I was listening to an episode of “Jews Talk Racial Justice with April and Tracie” in which hosts April Baskin and Tracy Guy-Decker were unpacking the pain that the recent incident at Colleyville and other synagogue attacks have unearthed in the Jewish community, particularly the White Ashkenazi Jewish population. April notes how an ingrained sense of “Jewish terror” built up over centuries often creates a barrier to seeing and showing up for other oppressed groups. They talked about how “many Jews have not had adequate libertatory trauma healing to support and synthesize this in a way that it works through their system and doesn’t trigger deep terror that locks down part of their heart, including their courage center and their capacity to do effective racial justice work.”

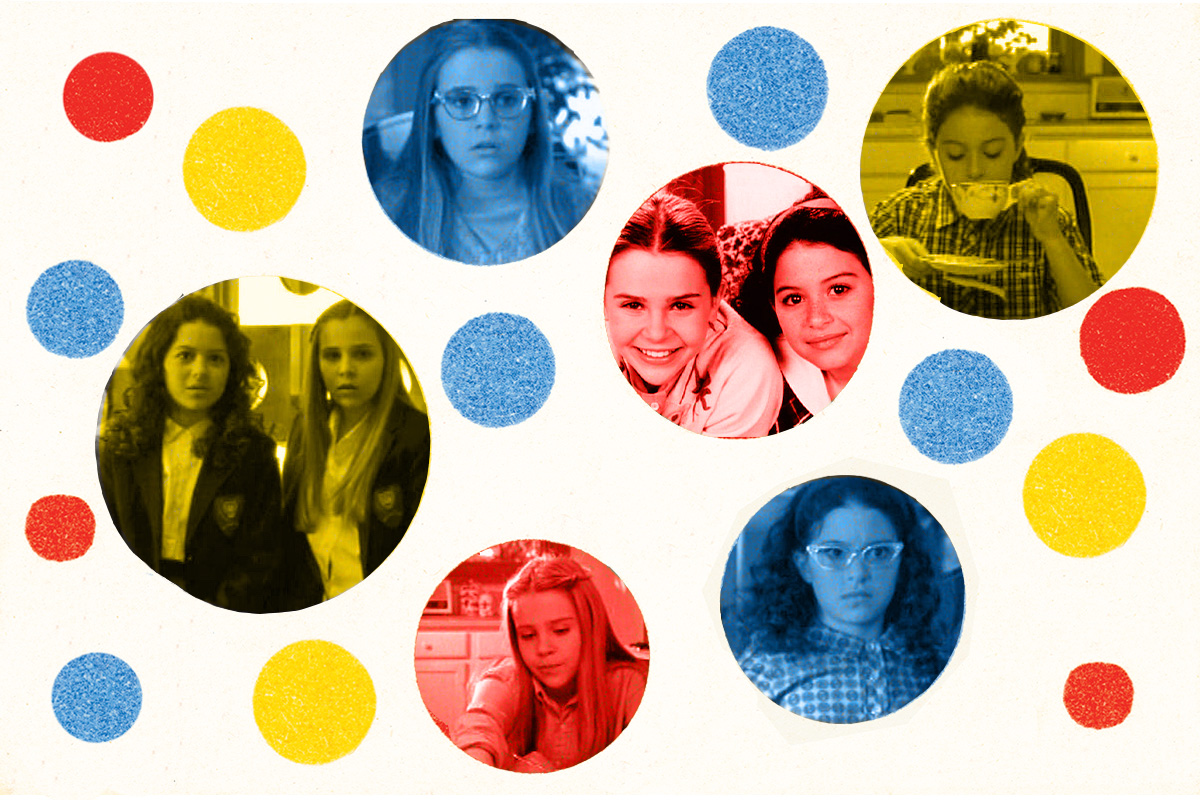

In searching my brain for what that healing could look like, my mind turned, as it occasionally does, to a little TV show I remembered from the early 2000s called “State of Grace,” created by Brenda Lilly. A female version of the “Wonder Years,” it features a little Jewish girl named Hannah Rayburn (Alia Shawkat), who moves with her family from Chicago to North Carolina in the 1960s and bonds with Grace McKee (Mae Whitman), an iconoclastic blonde rich girl at her local Catholic School. In addition to cult TV icons Whitman and Shawkat in their earliest roles, the show also boasts Oscar winner Frances McDormand as the voice of adult Hannah. I remember being vaguely aware at the time that neither of the actors playing Hannah were Jewish, but also feeling that their performances were effective enough that the issue never bothered me.

I didn’t remember much about the show – it only ran for two seasons and isn’t streaming anywhere legally. What I did remember was an adorable sapphic bond between Hannah and Grace that sparked queer feelings I didn’t know I had and a really great scene where Hannah’s father is revealed to be a Holocaust survivor that, at the time, I found really poignant. A parent of one of my middle-school Hebrew school students had also asked me for recommendations about age-appropriate resources to introduce them to the horrors of WWII, so I thought I would seek it out.

I ended up finding the episode in question on Youtube. Rewatching, I was nervous about how an older show about two white girls in the South would handle race. Fortunately, while it’s safe to say it wouldn’t pass the DuVernay test, overall the show’s treatment of the Civil Rights Movement is sanitized, but respectful, on par with late 90s early 2000s liberalism. A more whimsical time warp experience was that clearly someone had originally taped on VHS, complete with commercials for 1-800-COLLECT and Ben Affleck’s “Daredevil.”

Despite the graininess of the upload quality, my heart still swelled when the “Do You Believe in Magic?” theme song came on over the opening credits. Holy cow is the chemistry between Hannah and Grace queerer than I remembered. Grace has this breezy, Mae West fabulousness that infuses her every look and gesture, and Whitman devours the material with relish. Given that the most excitement Hannah tends to get in her life is testing cushions at her family furniture company, it makes complete sense why the well-behaved Hannah would allow Grace to sweep her off her feet. Grace also provides the gateway for Hannah to transgress from the “good girl” role that has been laid out for her. In this episode, Grace transforms her basement into the magical land of “Rayburnia,” where they strut about with mock french accents and paint brushes as prop cigarettes. Hannah becomes a dapper butch icon in this scene, sporting a bowler hat, trousers, and a fur coat. The sight of her next to Grace’s high femme dreamboat screams #relationshipgoals.

But there’s a darker side to Hannah’s attraction to Grace, which brings out Hannah’s internalized self-hatred. In preparation for Grace’s first sleepover at her house – which Hannah refers to as the first of many “bad first dates” – Hannah pushes her family to tone down their Jewishness so the WASP-y Grace won’t think they’re strange. In a later episode, Hannah gets invited to a fancy party at Grace’s house, but says her family can’t come because “they don’t go out at night.”

Hannah’s family is a fascinating constellation of 20th century Jewish American experiences. There’s Hannah’s father David, a Holocaust survivor from Poland who has built himself into a successful businessman. Grandma Ida fled the Cossacks in Ukraine and raised Hannah’s mother Evelyn and Uncle Hesche in the Great Depression. Evelyn has responded to the instability of her early life with anxiety over their family business and protectiveness over Hannah, while Hesche has fallen back on the age-old Jewish tradition of using humor to diffuse discomfort. All of Hannah’s family members contain oceans of history within them, but, in the 1960s, unpacking those feelings wasn’t exactly something you did with children, so Hannah just sees her family as weird, repressed and silent.

While Hannah is so busy making sure her family impresses Grace, she doesn’t consider the impact Grace’s brashness will have on her family. In that same scene where the girls are playing dress-up, they come across a box of photos filled with people Hannah doesn’t recognize. Hannah’s father, David, comes in and angrily snatches the photos away without explanation. Savvy viewers will deduce that these are pictures of family members who died in the Holocaust, but Hannah and Grace are left dumbfounded.

The discomfort continues at dinner. “So, Hannah says you all are Jewish,” She blurts out. “That is so neat! I’ve always wanted to be tortured for my faith.” Grace then goes on to detail the gruesome deaths of her favorite saints, to the stunned silence of the Rayburns – with the exception of Uncle Hesche. “Death is funny,” Grace remarks, “I’m not afraid of it at all.” She then offhandedly reveals that her own father died, but she looks forward to seeing him in heaven. Later, while washing dishes, Grace comments on the tattooed numbers on David Rayburn’s arm, and Hannah holds her breath. Rather than reprimand Grace, David calmly explains what happened when the Nazis invaded his home in Poland and killed most of his friends and family. David and Grace are both deeply wounded people who connect over a shared sense of loss.

Instead of being relieved that her friend ended up getting along with her family after all, it’s Hannah’s turn to get upset; jealous that her father was able to talk to Grace about his experiences as a Holocaust survivor in a way he never has with Hannah. Eventually, this experience motivates David to open up to Hannah about the family members in the photos – one of whom she is named after. It’s a meaningful step in helping David talk to his daughter about his trauma.

While Hannah and Grace come from wildly different worlds, it’s clear the girls are drawn to each other due to their desire to be held and seen. During the tense dinner scene, Hannah’s voice-over reveals that in her family, “emotional issues were a non-topic. If it couldn’t be yelled down the stairs, it simply wasn’t worth discussing.” In Grace’s case, her mother has basically left her to parent herself since her father’s death, preferring to escape her pain through parties, drink and travel. In Grace, Hannah finds a release valve from the culture of silence that has built up around her family’s traumas, and Grace finds, in the Rayburns, a source of family support and stability that she lacks (despite her vast wealth).

This sense of the Jewish family as a source of wholesome support is also what makes “State of Grace” powerful and stunning 20 years later. Though the Rayburns are all clearly recognizable Jewish types, they never fall into broad stereotypes or nastiness toward each other. While there have certainly been other times I saw Jewish families I recognized and connected with on screen, for instance the Pfeffermans in “Transparent” and the Maisel/Weisman clan of “Marvelous Mrs. Maisel,” the dysfunction on those shows can be overwhelming. While watching the Rayburns certainly prompts us to, as The Good Book “Crazy Ex-Girlfriend” says, “remember that we suffered,” the sweet manages to shine through the bitter. We don’t just get to witness or laugh at the Rayburns’ traumas, but watch them process, heal, and find new ways to support each other.

“State of Grace” is a tender way for someone like my fifth grader to start learning about painful Jewish history. It could also be a great gateway for Jewish adults to help them find wholeness.

In that same episode of “Jews Talk Racial Justice Podcast,” April and Tracie talk about the need for American Jews feeling isolated by centuries of grief and fear to allow themselves to be held, for their pain to move through their system. The tenderness with which the Rayburns are able to unclench and open up to each other about their grief can serve as a model for how American Jews can start to articulate the fears we have about our own sense of security. While many of us with white privilege have been able to find financial success and stability by assimilating into American culture, we still have unhealed generational traumas. It’s important to find ways in which we can articulate them – not only to be able to be there for those we love, but also those outside of our community. When we haven’t healed, we can fall into protectiveness and close ourselves off to other communities that are suffering from white supremacy. But when we do that healing work, “we can start,” as Tracie says, “to show up, to be the folks we wish we had had, so that we can then create the world where we show up for one another.”

Late Take is a series on Alma where we revisit Jewish pop culture of the past for no reason, other than the fact that we can’t stop thinking about it?? If you have a pitch for this column, please e-mail submissions@heyalma.com with “Late Take” in the subject line.