Growing up, I always looked forward to Passover. Something about a festival dedicated to the celebration of physical and spiritual redemption from suffering struck a chord with my childhood self. Of course, it’s also a joyful remembrance of journeys and paths toward freedom.

Somewhere along the way, though, I stopped eagerly anticipating the holiday. Instead, I reserved that enthusiasm for spring break, which was usually scheduled around the same time of year. I longed for a respite from school and the constant discomfort those locker-lined hallways represented. At the time, I mostly associated my queerness and Jewishness with hastily drawn swastikas on peer-graded assignments and muttered homophobic taunts.

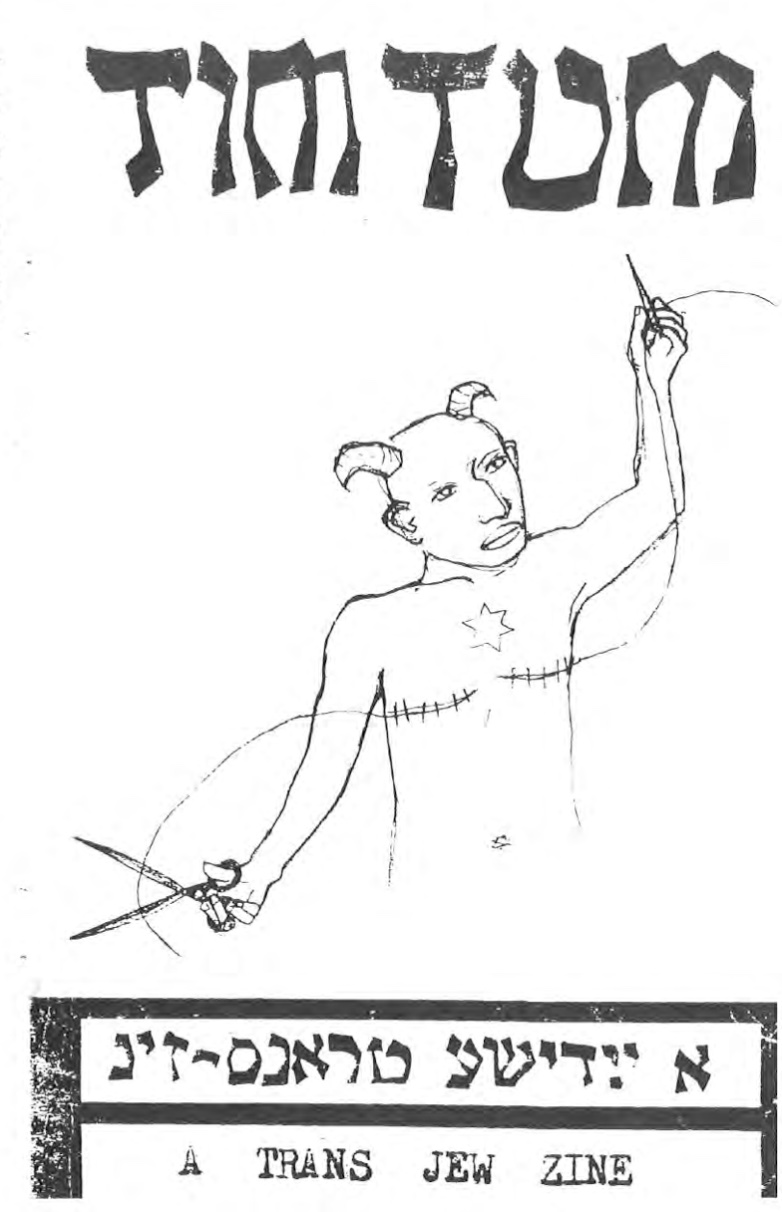

When I encountered a zine written by Micah Bazant, I began to think differently about what it meant to be queer and Jewish. Not far into their 1999 zine, “TimTum: A Trans Jew,” Bazant makes a subversive assertion. “I feel like Judaism is a secret package delivered to me through time, disguised and concealed, hidden from the enemy,” they write. “I feel a responsibility to the generations who sustained this, who died and lived as Jews. Who am I to throw away this most precious of gifts — now, when I am finally free to fully unwrap it.”

I paused over this. I went back and reread the entire page from the beginning. Then I skimmed ahead for further discussion of Bazant’s relationship with Judaism. I was enthralled. Across a series of essays, drawings, emails and prayers, Bazant provides a vital narrative of resistance. And until I read Bazant’s zine, I had never seen myself so clearly represented.

The first time I read “TimTum,” I couldn’t help but think about the tradition of reading the haggadah to guide my family’s seder during Passover. Much like haggadot tell a story of resiliency and freedom, so too does “TimTum.”

At the heart of Bazant’s zine is the assertion that suffering and oppression are not the only defining experiences tied to their queer and Jewish identities. Instead, Bazant suggests that Judaism is a way of demanding a rich, embodied existence, not just survival.

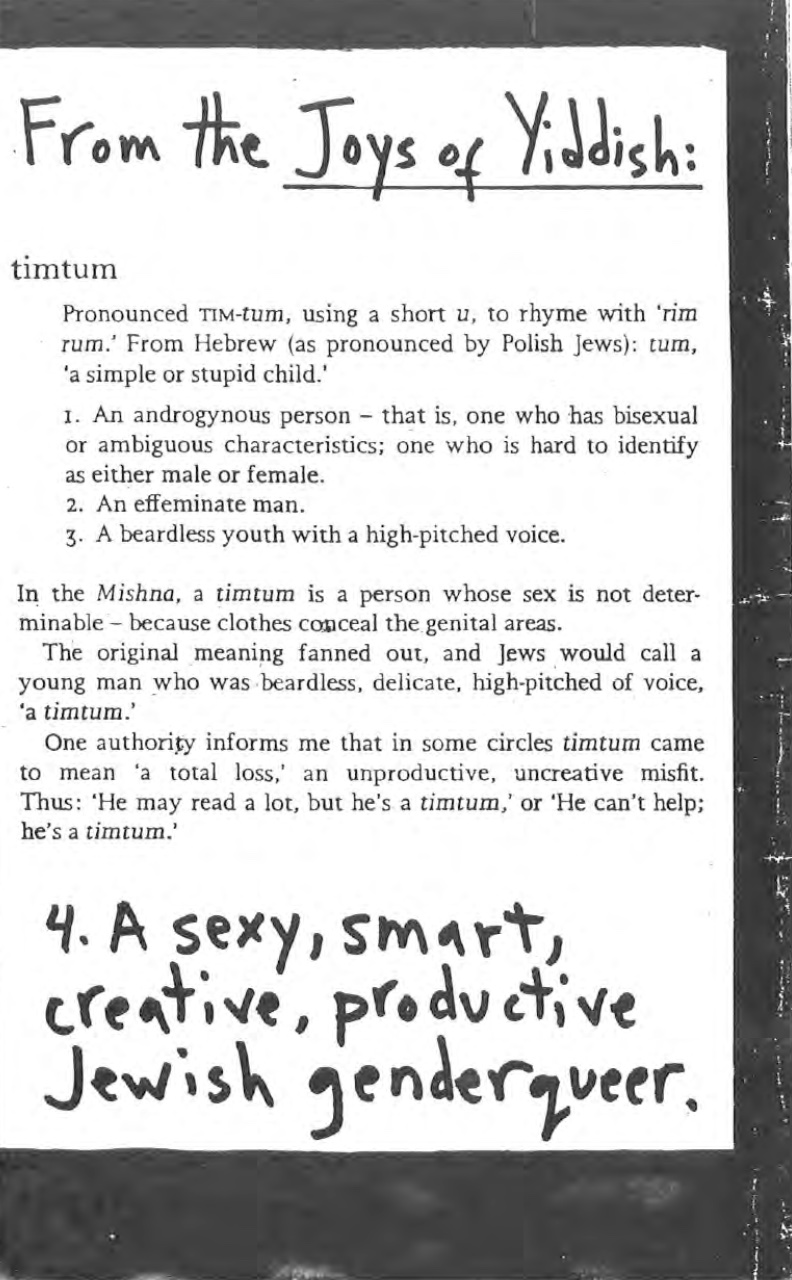

Timtum is a Yiddish word that defies simple definition and was initially derived from the Hebrew word tumtum.

Rabbi Elliot Kukla, the first trans person ordained by Hebrew Union College in Los Angeles, introduced the concept of the tumtum to the general public in 2006. He encountered it at the age of twenty while studying at an orthodox yeshiva. His teacher defined a tumtum as a “mythical beast” invented by the Sages to test the limits of the law. In practice, the term tumtum was primarily used by the rabbis of the Mishnah to identify those who were neither male nor female.

Timtum usually has a negative connotation when referring to an androgynous person whose gender is not immediately obvious at first glance. But, in Micah Bazant’s reimagining, a timtum can also be “a sexy, smart, creative, productive Jewish genderqueer.”

Bazant’s timtum is visually arresting, with their self-performed needle and thread top surgery and a chest emblazoned with a tattooed Star of David. Gone is the hyper-medicalization of top surgery; gone is any undercurrent of guilt for prominently displaying a tattoo. Tattoos historically have been weaponized to dehumanize Jewish people — what could be a stronger declaration of agency than choosing to permanently display a Star of David?

But what really struck me the first time I read “TimTum” was the realization that queer, trans Jews have always existed — that the story of Passover is also a story of queer freedom. There must have been queer people among the liberated Israelites who crossed the Red Sea: These narratives are fundamentally entangled.

I realized nothing was stopping me from incorporating this information into my celebration of Passover. The word haggadah translates to telling, and this year, even after Passover ends, I’ll make sure to keep telling everyone I possibly can about the timtum.

By choosing to live fully, queer Jews resist societal norms through their continued existence. This Passover, as transphobic and homophobic legislation loom and antisemitic violence surges, “TimTum” provides a model of revolutionary survival.