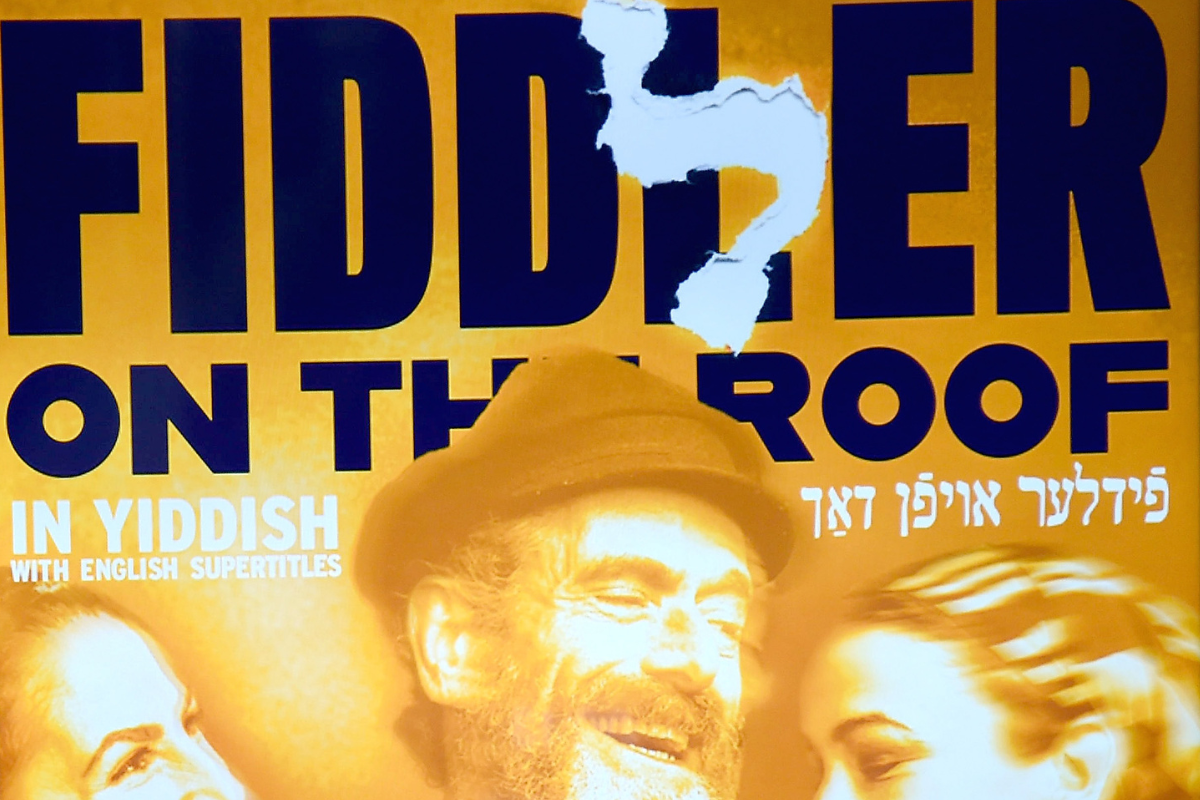

Before the pandemic, before all the theaters closed, I managed to snag a few tickets to the Yiddish performance of “Fiddler on the Roof” for my grandmother and myself. Though I had previously seen the earlier American Broadway revival, and had already watched the 1971 film adaption of the Sholem Aleichem story too many times to count, I was invested in seeing this particular version because of its linguistic connection to my grandmother.

I felt my grandmother, who had spoken Yiddish in the early period of her life, might get access to the show in ways that English productions would not have given her. Yet I was still astounded by the degree of her reaction after the performance, when she turned to me with tears in her eyes, saying in Russian that “this” (the performance) was just like how it was.

To provide some context: My paternal grandparents grew up in what is today known as Kyiv, Ukraine. While both my grandfather and grandmother spent some of their youth in urban pre-USSR city environments (with all the antisemitism that that entails), I learned that the former spent his early life in villages like Anatevka — as did their grandparents, my great-great grandparents.

So while others — particularly non-Jewish audiences — see the setting of “Fiddler” as some quaint nostalgic far-off land filled with matchmakers and overly dramatic dairymen, for my grandmother, the world portrayed in this show was closer to history than fiction. Closer to a life I could have lived, a life that members of my family had actually lived.

As a creative, I do not think it would be an exaggeration to say that a majority of Jewish art is based on memory. With each attack on our people, each attempt at physical and mental annihilation, each destruction of human lives and their art (books, hand-crafted Judaica, etc.), Jewish individuals past and present have made it their calling to preserve Jewish heritage — whether it’s historians and activists undergoing extensive efforts to recover Nazi-looted art, or Jewish artists attempting to recreate Jewish landscapes lost to the passages of time.

An clear example of this can be found in the work of Russian-Jewish artist, Marc Chagall. Influenced by his family’s roots in Hasidic Judaism as well as Russian-Jewish folk art, many of his paintings appear as both mirror and ode to the shtetl life that he grew up in: dream-like worlds populated by farmers, animals, flying rabbis — and, yes, a fiddler dancing on a roof.

“The Fiddler” (1912) is the visual embodiment of Tevye’s iconic words from the beginning of the 1971 film: “A fiddler on the roof. Sounds crazy, no? But here, in our little village of Anatevka, you might say every one of us is a fiddler on the roof trying to scratch out a pleasant, simple tune without breaking his neck.” The Fiddler character is the embodiment of tradition, a figure both tragic and comedic. He is quintessentially Jewish, for being Jewish was, and continues to be, an identity intertwined with danger; he exists in a liminal space, yet creates beauty and art all the same.

As my Russian-Jewish comparatives studies instructor, Lily Alexander, said to my class regarding Marc Chagall, he is a demiurge (a creator god) capturing lost worlds through his art. And that is essentially what “Fiddler on the Roof,” Anatevka, is. A lost world.

There will never be another world like the shtetls, either the one featured in Sholem Aleichem’s words, or Marc Chagall’s art, or even my grandmother’s memories. Part of that is due to the natural evolution of time, but primarily to the unnatural act of erasure through violence, of pogroms and wars wiping out so much of our past.

Even the 1971 film is a testament to the curious nature of fact becoming fiction, as part of the film had been filmed in what was then Yugoslavia, a territory that no longer exists. The film crew even had to re-create a wooden synagogue for one of the film’s settings based only on photographs and historian’s words, because no wooden synagogues existed in Eastern Europe after World War Two thanks to them being all burned down during the Holocaust.

Jewish art is memorial, both to the pasts that once existed and the pasts that could have been, the Jewish lives that could have happened, if they had been allowed to live.

Though the “Fiddler on the Roof” film is half a century old, having just celebrated its 50th anniversary (including a documentary commemorating the making of the 1971 production) it and the original story of Fiddler of the Roof continues to hold immense significance for generations of Jewish viewers, including those like myself and my babushka.

For a Ukrainian Jewish American like me, “Fiddler on the Roof” gives me a glimpse of my family’s past growing up in the shtetl, speaking Yiddish and being surrounded by Jewish customs in ways I can only imagine. While as a secular Jew, the majority of American Jewish media did not seem designed for people like me, “Fiddler on the Roof” offered me something valuable to help me feel valid in my Jewish identity as well as provide a window into a lost past.