For as long as there have been Jewish people, there have been questions about what it means to be a part of the Jewish people. Our oldest and most sacred texts feature heroes of the Jewish people struggling with, doubting, and even rejecting what it means to be a Jew.

Today, this reckoning continues. Jews of Color, queer, gender expansive, and disabled Jews ask, “Do we belong?” As we see progressive social movements shift our society ever closer to justice, some ask, what does this ancient tradition offer me today?

I know that I am not alone in admitting I have these questions, but I was surprised to learn that these enormous questions about the very nature of Jewish existence were being asked head-on at my Washington, D.C. synagogue.

Through the lens of Jewish artistry, the “Authenticity and Identity” exhibit at Adas Israel Congregation features almost 70 artworks from over 40 artists across the globe. Half of the artists are D.C. locals. The exhibit grew out of a call put out in 2018 for any Jewish artist to submit pieces that wrestle with themes of authenticity and identity. Yet no boundaries were put in place. There was no fine print to qualify which people counted as Jews and which didn’t; Jews of color, converts, patrilineal Jews, queer and trans Jews, Israeli secular Jews, assimilated Jews, and Jews of all denominations were encouraged to submit their work. What resulted is a breathtaking exhibition of doubt, uncertainty, pride, and affirmation. (Full disclosure: I was previously employed by Adas and now work as a volunteer guide at their mikveh.)

As I walked through my beloved synagogue for the first time in over a year, I couldn’t help but notice how chaotic the art seemed. The gallery begins immediately upon entering the building, with sculptures and hanging tallises and paintings taking up three parts of the lobby. Then, it continues down hallways. Paintings, kippahs, and shoes curve around the Beit Midrash. In front of the sanctuary stand room dividers covered with tzitzit, tallits, and photographs. Art hangs from the ceilings and the walls, decorating the heart of Jewish life with the questions, “Am I a Jew? Am I Jewish enough?”

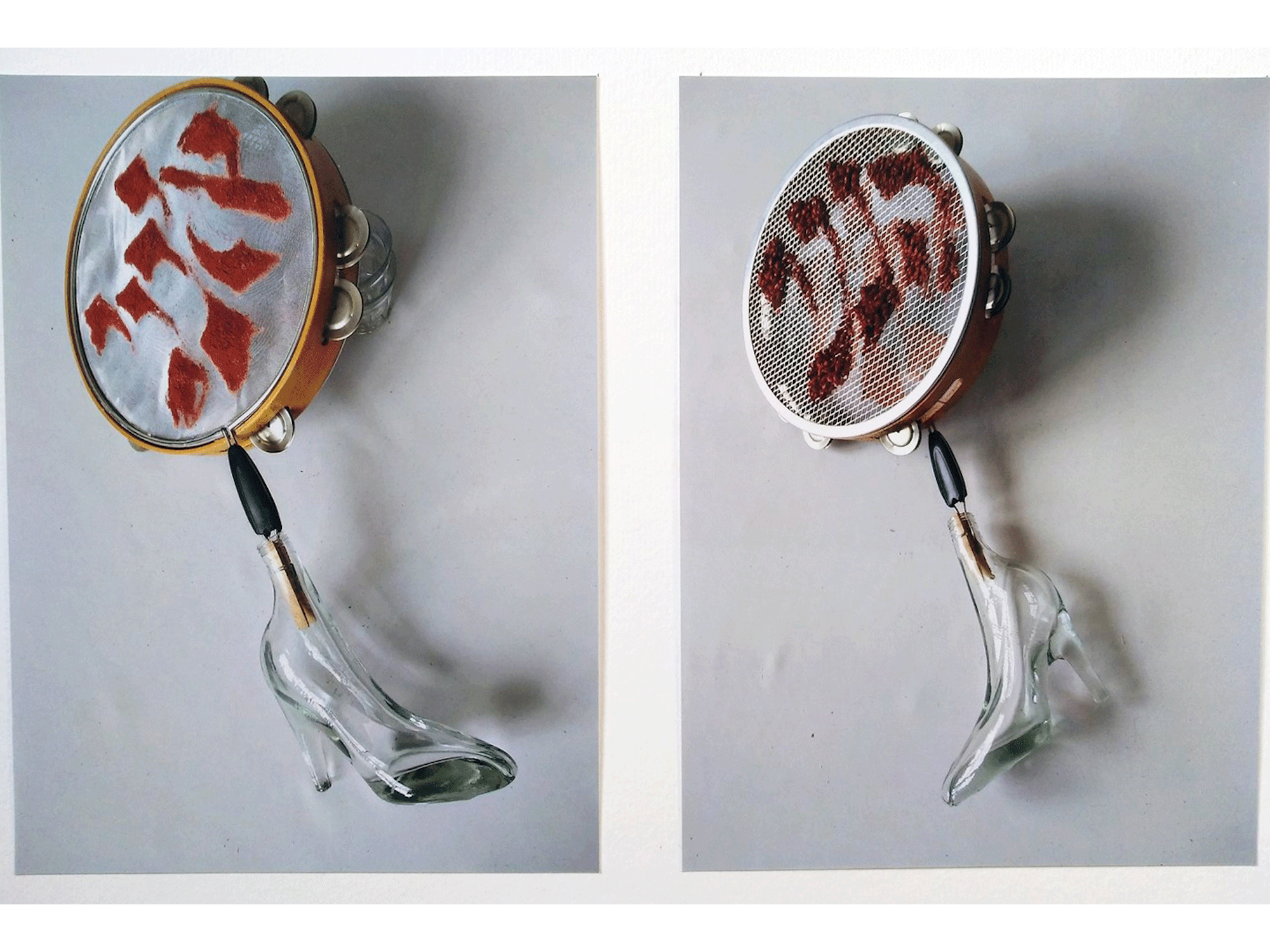

One such piece is “Hineni, Eineni” by Billha Zussman. Zussman, a Netherlands-based artist, embroidered the Hebrew word hineni, “here I am,” on one side of a timbrel of Miriam. Instead of the reverse of the word on the other side, we find the word eineni: “I am not.” The timbrel rests in a literal glass slipper, alluding both to the ways in which women are allowed to show up in the Jewish traditions and to the ways in which a glass ceiling still holds us back.

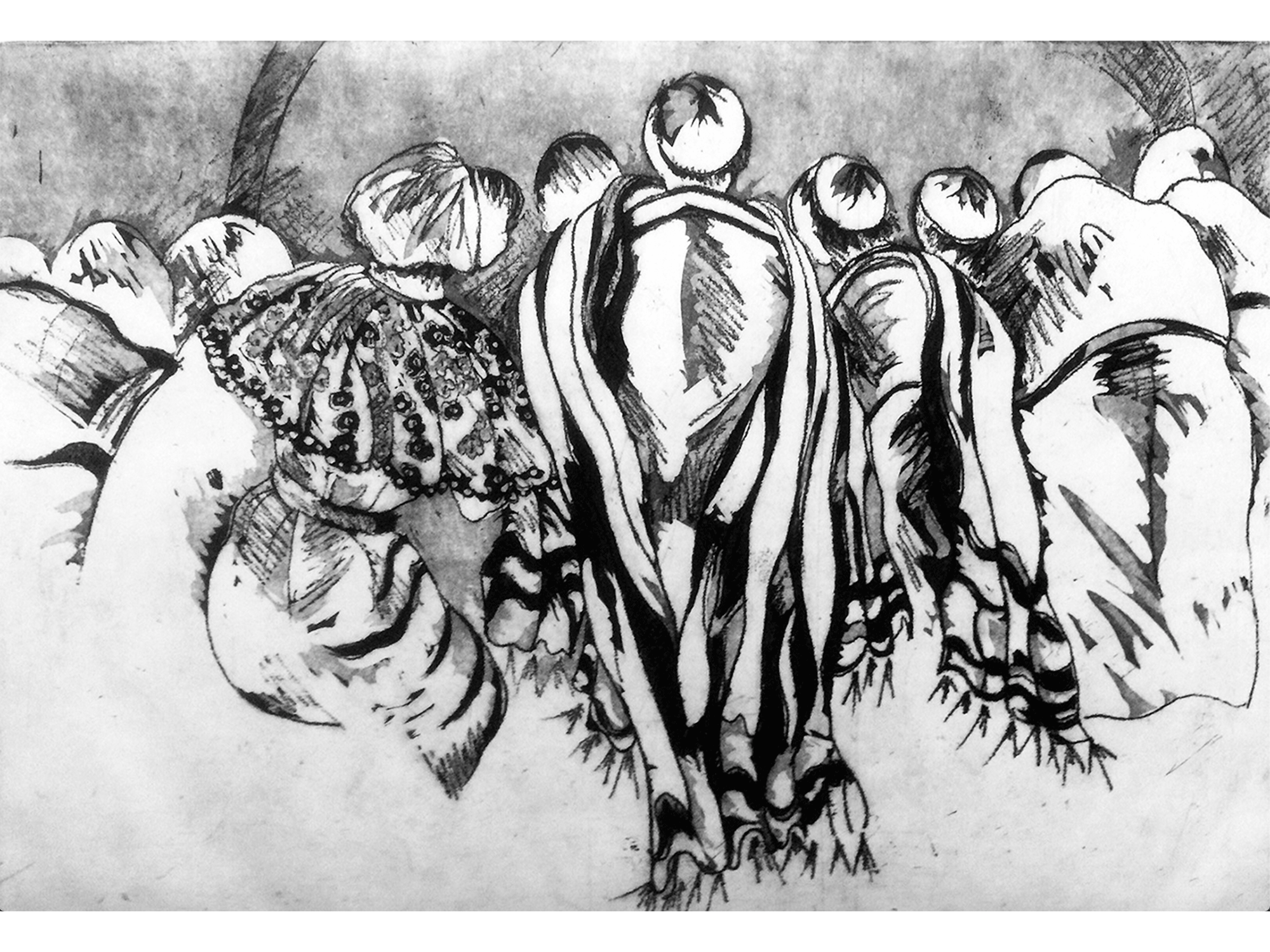

Another piece is “Kaddish After Pittsburgh” by Joyce Ellen Weinstein, an etching that depicts the backs of several figures, hunched away from the viewer, donning kippahs and tallits. The horrors of the synagogue shooting to which it refers are not shown. Instead, the piece focuses on the quiet, mournful response to the targeting of Jews who worked to welcome immigrants and refugees.

Elsewhere, a kippah by Jacob Rath stands in a display box, depicting a print of a cherubic Santa Claus. Does the addition of Santa make the yarmulke any less Jewish? Would wearing it with the addition of Santa nullify the holiness of the mitzvah? As the child of an interfaith marriage, as someone who proudly celebrates Christmas, as someone who has worked exceptionally hard at pulling myself out of the hole of assimilation that my family was forced to dig for generations in a Christian supremacist society, I find this tongue-in-cheek piece striking. What does it mean for me to hold these particular identities? Were I ever to wear this kippah, what would my fellow Jews think? Would it matter?

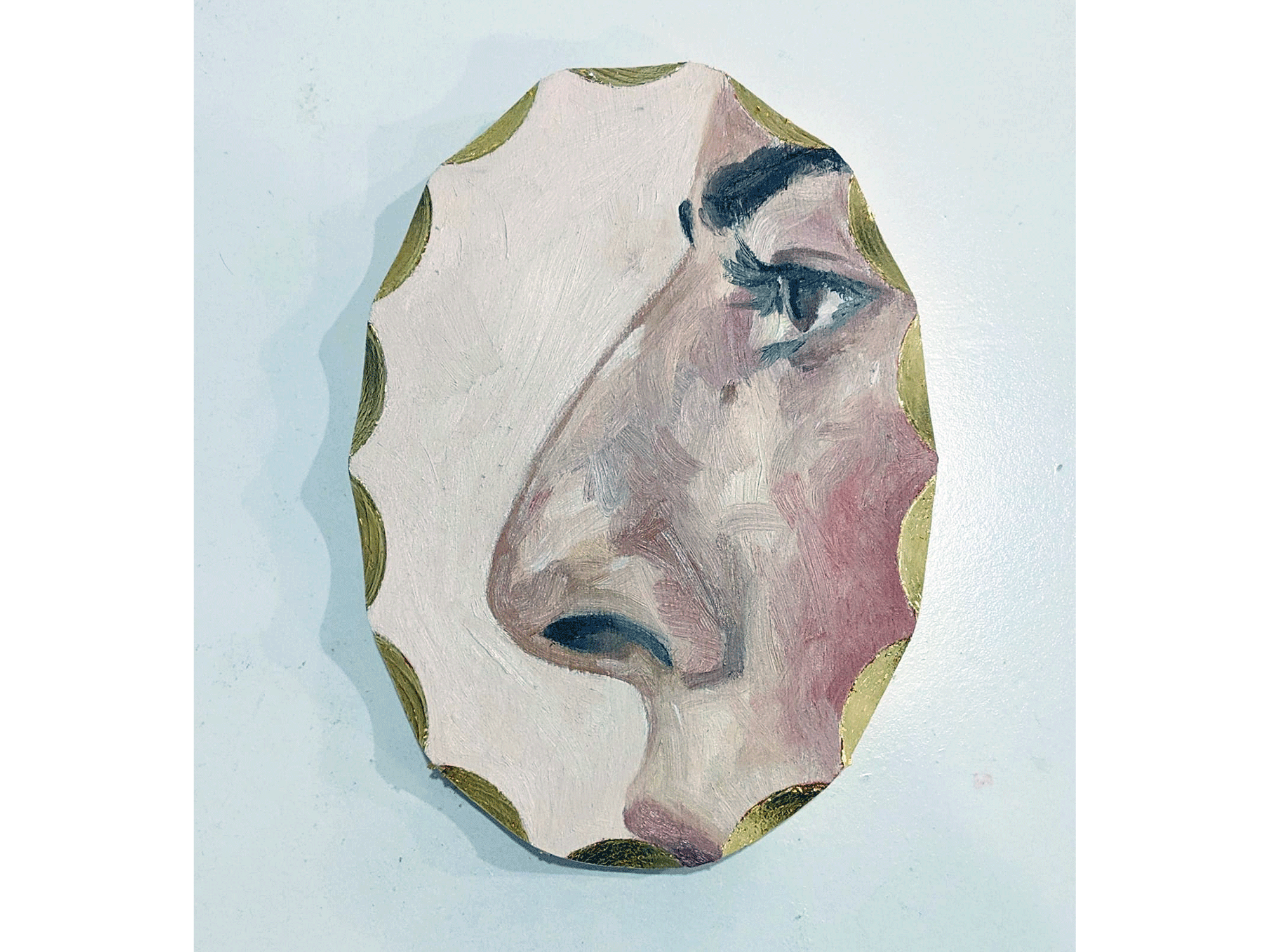

Another piece that asks questions about perceptions of Judaism is “My Jewish Nose” by Goldie Gross. Though one might think of a traditional silhouette portrait as featuring someone’s whole face, Gross hones in on just the nose, framed by a hint of cheek and eye. She seems to ask, what is a Jew supposed to look like? If Jews don’t look like this, are they less Jewish? I’m six feet tall and zaftig. I don’t have a larger nose and my hair is straight. When I walk into a synagogue, I generally don’t see myself physically reflected in the community. Often, neither do Black Jews or genderqueer Jews. Do these “Jewish” features define Judaism, or do they create an imposed boundary around who belongs within and who must stay outside?

Since walking through the gallery, I haven’t been able to shake the art from my mind. It’s deeply profound to curate an entire exhibit on the basis of uncertainty and expansiveness in the first place. But by housing these questions in a central place of worship and community, “Authenticity and Identity” has reminded me that questioning and exploring the very boundaries of Jewish identity is one of the most Jewish experiences of all.

Authenticity and Identity, curated by Ori Z Soltes, is on display at Adas Israel Congregation in Washington, DC. Timed tickets are available to the public until May 14th and a virtual gallery is accessible to anyone online.