“Jews in Old Postcards and Prints” is a brand-new collection of vintage postcards and antique prints annotated by Lars Fischer. The book sheds a thoughtful light on the history of Jews in Europe and around the Mediterranean, mainly in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and invites readers to reflect on the ways in which both Jews and non-Jews used postcards and prints to portray Jews, their communities, culture and institutions.

Above all, the book celebrates the vibrancy and diversity of Jewish life and culture in the “golden age” of the postcard, a world largely extinguished by the Holocaust and the expulsion of Jews from Northern Africa.

As Fischer writes in the introduction, “While some readers may be familiar with many of the images and many will recognize some, I am hopeful that everyone will come across something new in this book. Above all, I hope that readers will find it both informative and entertaining, our knowledge of the shadow of destruction hanging over so many of the images notwithstanding.”

Here are some highlights:

Middlesex Street – Jews’ Free School, London

The view shows the juncture of Sandys Row and Middlesex Street close to the northern end of Middlesex Street (near Liverpool Street Station) with one of the entrances to the Jews’ Free School on the left. Some of the young men at the center of the image were presumably pupils of the school.

Located on the border between the City and Whitechapel, Petticoat Lane — where the Huguenots of Spitalfields had established a textiles market — was renamed Middlesex Street in the mid-19th century, but the Petticoat Lane Market, which in fact takes place on Middlesex Street and Wentworth Street, has retained its name. From the late 19th century until the middle of the 20th century, most of the tradesmen and women and many of the customers were Jewish. The area was frequently referred to simply as “the Lane.”

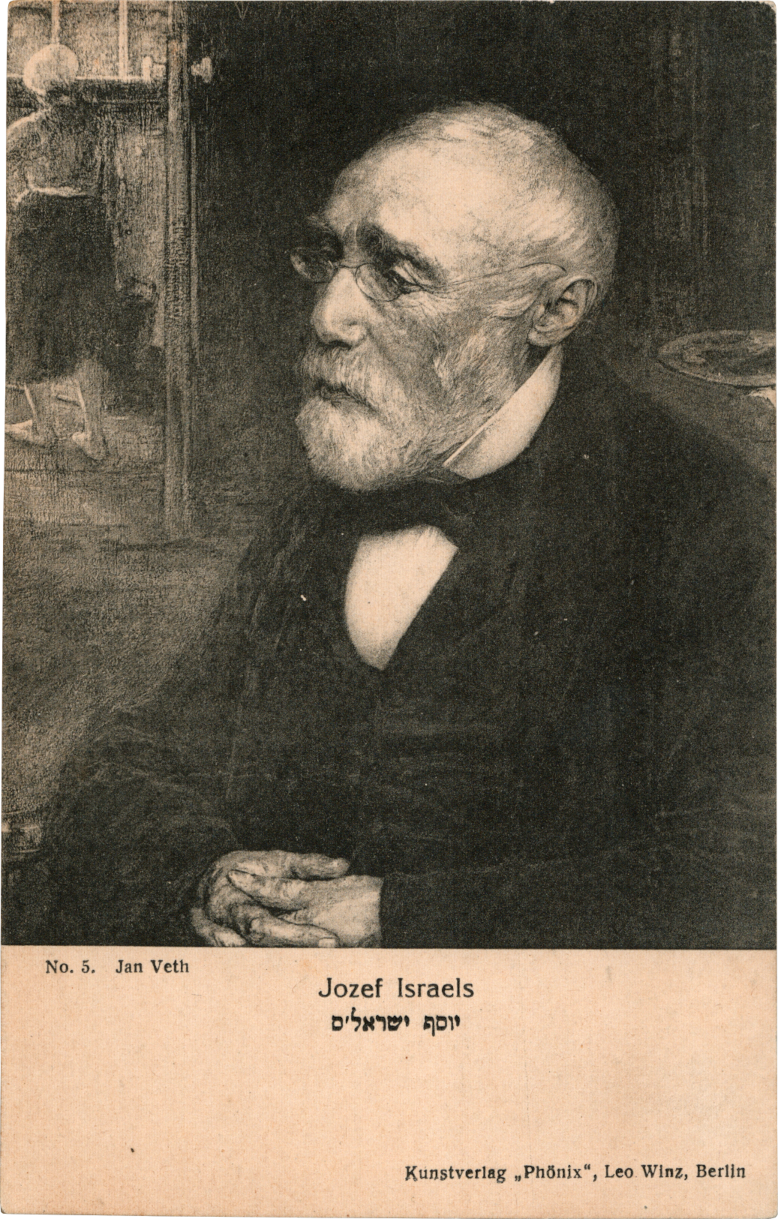

Jozef Israëls

Jozef Israëls (1824–1911) was born into a Jewish family of modest means and enjoyed a traditional Jewish education. He is generally considered the greatest Dutch painter of the 19th century. He was particularly well-known for his portrayals of the dire circumstances of many North Sea fishermen and their families, as well as a number of paintings with Jewish motifs, notably “Son of the Ancient People.” Isaac Israëls (1865–1934) trained with his father and became a leading Dutch impressionist.

Draguignan – The Jewry

Jews lived in Draguignan, a village roughly 50 kilometers north of Saint-Tropez, from at least the 13th century. In the mid-14th century, the self-governing Jewish community in Draguignan numbered between 200 and 250 members, and in the early 15th century the Jewish quarter was no longer able to hold them all. Jewish life in the village ended with the expulsion of 1501.

View of the Muidergracht, Across the Academy Garden, Towards the Jewish Church and Other Noteworthy Buildings

The print shows just how striking an addition the new Portuguese (Sephardi) Synagogue (Esnoga), inaugurated in 1675, was to Amsterdam’s cityscape. Designed by Elias Bouman (1635–1686), one of the city’s leading (non-Jewish) master masons who had previously worked for a number of other Jewish clients, the Esnoga reflects the style of various prominent Dutch buildings at the time.

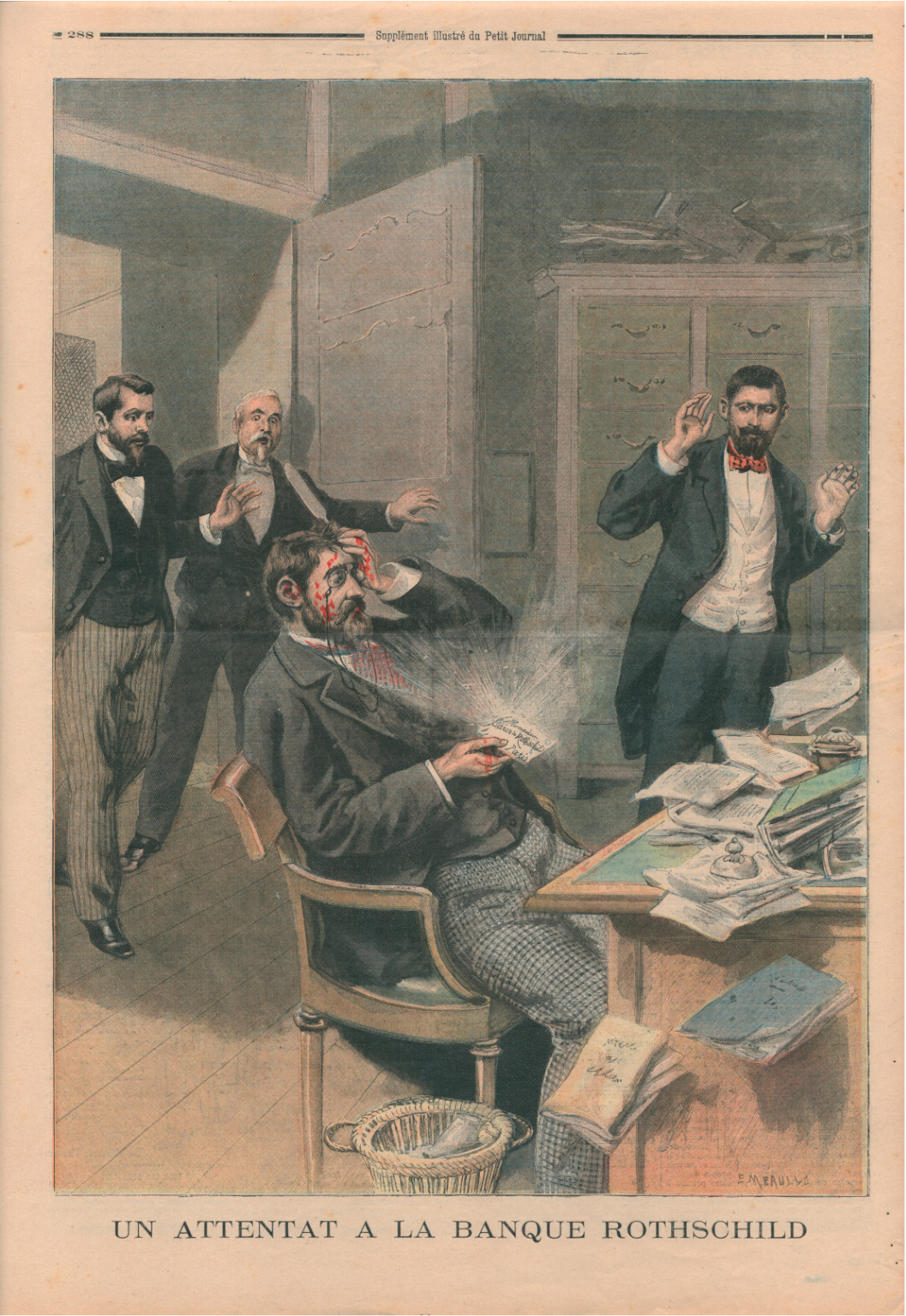

Assassination Attempt at the Rothschild Bank

In August and September 1895, the Rothschild Bank in Paris came under attack. First, a letter bomb sent to Alphonse Rothschild’s home and taken to his office injured his principal secretary, Bernard (Isaïe) Jodkowitz (1841–1921). On September 5, the anarchist Léon Bouteilhe walked into the bank with a bomb that failed to explode when he lit the fuse.

On August 31, 1895, The Graphic commented: “One of the fixed ideas of the Socialists of every variety of tint is that the Rothschilds are the supreme embodiment of the Capitalism and Individualism on which contemporary society is founded. Given this principle, given also the existence of Anarchists who believe in the Propaganda by Deed, given furthermore a continuous output of incendiary literature pointing to the Rothschilds as the chief source of every social ill, and, on the other hand, a not inconsiderable band of reckless exaltés ready at any moment to throw bombs in vindication of their delusion, and the only wonder is that the explosive letter sent to Baron Alphonse de Rothschild in Paris last Saturday, should have been the first attempt to execute Anarchist justice on the arch-millionaire. The probability is that it was not the first enterprise of its kind, for the Rothschilds are so obvious a quarry for the thunderbolts of the Catastrophists, that it is difficult to believe that no Anarchist has hitherto attempted to get at them. … The letter bomb used in the present case is a comparatively new device, and illustrates in a striking manner the readiness of the Anarchists to adapt themselves to the restricted scope forced upon them by police vigilance. The placing of infernal machines inside or outside of public buildings is no longer an easy matter, and hence the manufacture of the epistolary bomb and its transmission through the post.”

Jewish Builders

At first glance, readers may be reminded of Lewis Hine’s famous series of photographs of construction workers erecting the Empire State Building in New York. The development of the Yishuv entailed numerous substantial infrastructure projects, creating an enormous demand for construction workers. In addition, Zionists were keen to emphasize that, contrary to myth, Jews were no less capable of strenuous physical labor than anyone else.

Photographer Ya’akov (Jacob) Benor-Kalter (1897–1969) was a prominent member of the pioneering generation of photographers in the Yishuv who predominantly came from the Austrian part of Galicia that became part of Poland after the First World War. In 1927, he designed a series of postage stamps for Palestine. His photography became more experimental in the 1930s, and he subsequently worked primarily as an architectural designer. Samuel Adler apparently came to Palestine from Germany in 1933 and began to produce postcards, mainly with motifs by Benor-Kalter, the following year.

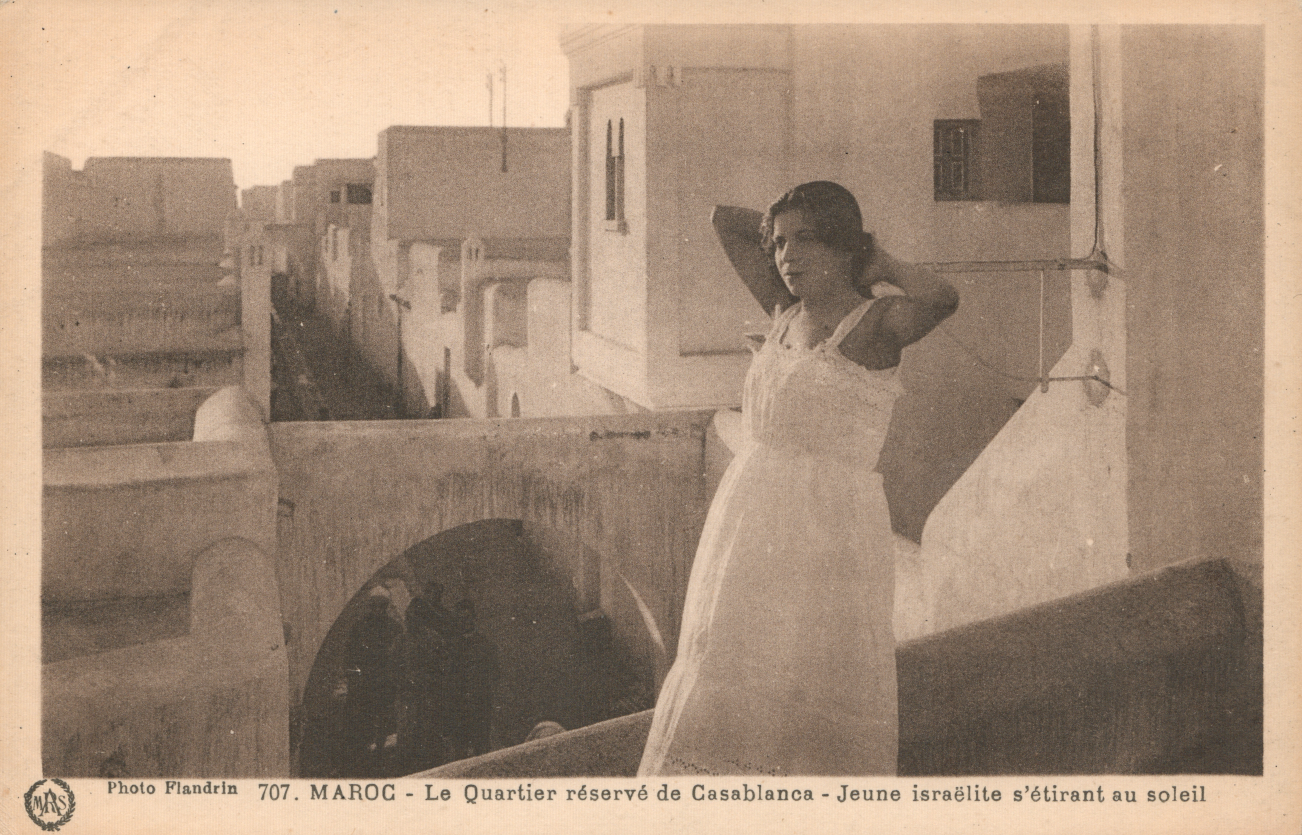

Morocco — The Red-Light District in Casablanca — A Young Israelite Woman Stretching Out in the Sun

Jews did not settle in Casablanca in significant numbers until the 19th century. On the eve of the First World War, roughly five thousand Jews lived in the city — making up a quarter of its population. Casablanca grew considerably in subsequent decades, and the number of Jews increased to 20,000 in 1926 and the best part of 40,000 10 years later. In this period, the wealthier Moroccan Jews increasingly moved out of the mellah, joining their Algerian and European brethren and the bulk of the non-Jewish European population in the ville nouvelle, the new neighborhood recently constructed alongside the Old City and mellah. At its height, the Jewish community maintained no fewer than 80 synagogues in the city. Casablanca hosted the Moroccan headquarter of the Alliance Israélite Universelle which, alongside various other charitable activities, ran the Jewish school system in the French Protectorate.

The overwhelming majority of Moroccan Jews now live in the city, making its Jewish community the largest in the country and, by extension, in the Arab world. Among the modernization measures the French implemented after the First World War was the creation, from scratch, of a purpose-built red-light district, Bousbir, which opened in 1924. Ironically, while entirely failing to fulfill its intended purposes — the monitoring and containment of prostitution and sexually transmitted diseases in the city — it became Casablanca’s principal tourist attraction. It was designed by the French-born architect Edmond Brion as an entirely self-contained, gated entity to match what Western tourists would expect an authentic “Oriental” quarter to look like. Alongside a number of brothels, it also housed a sauna, a cinema, restaurants and various other leisure facilities and, much like today’s red-light district in Amsterdam, it attracted not only actual customers but large numbers of tourists who came to gawp and enjoy the titillation — on the postcard one can see several men in the street below staring up at the woman.

Kindergarten in Ein Harod

Kibbutzim — their childcare facilities included — were organized as collectives. Nurturing the young invariably features prominently in nation-building efforts. Established in 1921, Ein Harod, located 25 km southeast of Nazareth, close to Mount Gilboa, was a pioneering kibbutz and for many years home to one of the largest kibbutz associations, Hakibbutz Hame’uhad (United Kibbutz, established in 1927). It sought to foster kibbutzim combining the advantages of rural and urban existence and offering an ambitious intellectual and cultural life. Ein Harod created one of the first art museums — and the first purpose-built museum — in the Yishuv. Overseen for many years by the painter Haim Atar (1902–1953), it focused on avant garde rather than folk art. Its purpose-built premises were erected during the War of Independence — indicating how doggedly the project was pursued even at times of crisis. It houses works — often rescued before the Germans could loot them — by Jozef Israëls, Szmul Hirszenberg, Max Lieberman, Leonid Pasternak, Hermann Struck and Ephraim Moshe Lilien. The museum, which has since been enlarged, exists to this day.

Albert Grant

When Abraham Gottheimer (who changed his name by deed poll to Albert Grant in 1863) was born in Dublin in 1831, his parents were so poor that the local Jewish community had to supply them with everything needed to take care of the newborn. His father was a recent immigrant from a part of Eastern Prussia that is now in Poland. From 1859 onwards, Gottheimer/Grant ran a succession of high-profile international investment companies, most of which were essentially pyramid schemes. He also served as MP for Kidderminster. In 1874, Grant, who had a sterling reputation as an extremely generous philanthropist, acquired Leicester Gardens, then a derelict and unsafe former public garden, completely redeveloped it at his own (considerable) expense and then gifted the redeveloped Leicester Square, which has been a well-known landmark ever since, to the Metropolitan Board of Works for public use. Yet, 1874 was also the year in which he was no longer able to bribe journalists into hushing up his fraudulent dealings and his career came to an abrupt end. Although Grant converted to Christianity, he was still identified as a Jew not only by many of his non-Jewish peers but also by the Jewish Chronicle.

Mme Ida Rubinstein, Saint Sebastian

Orphaned at a young age, Ida Rubinstein (1885–1960), who converted to Orthodox Christianity (and later to Roman Catholicism), used her Jewish family’s banking money to set herself in scene, through dance, as a mythical princess-like figure. The Italian poet (and subsequent fascist) Gabriele D’Annunzio provided the text for The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian, Debussy the music. Mikhail Fokine choreographed, and the set and costumes were designed by the Jewish painter Léon Bakst (Leib Haim Rosenberg, 1866–1924).

Generations of scholars, enthusiasts and journalists have passed down the claim that Léon-Adolphe Amette, the archbishop of Paris, banned Catholics from attending the performances specifically because Saint Sebastian was embodied by a bisexual Jewish woman in the production. It is entirely possible, likely even, that all this contributed to his misgivings, but Amette did not in fact give any specific reasons to explain why (proper) Catholics should stay away.

Lausanne, Synagogue and Orthodox Church, Switzerland

Once Jews settled in Lausanne again in the 19th century, worship initially took place in private rooms and it would seem that only in 1900 was the community able to take up dedicated facilities in the newly erected Maison Mercier on Rue du Grand Chêne. When Daniel Osiris Iffla, whom we previously met as the patron who funded the construction of the Sephardi synagogue on Rue de Buffault in Paris, died, it transpired that among the various bequests he had made in his will — including, rather bizarrely, funds for a Wilhelm Tell monument in Lausanne — were 50,000 Francs for a purpose-built synagogue in the city. Back in 1874, he stipulated that the synagogue on Rue de Buffault should be built on the model of the house of worship that had burned down the previous year in his home town of Bordeaux. His bequest now was conditional on the prospective synagogue in Lausanne following the inspiration of the synagogue on Rue de Buffault. Located at what were at the time the outskirts of the city, it was inaugurated on 7 November 1910 with local, regional and state dignitaries in attendance. When the new Greek Orthodox church constructed adjacent to the synagogue was inaugurated 1922, it was not the first time that this community followed in the footsteps of its Jewish counterpart. On 27 September 1912, the Zürcherische Freitagszeitung reported that the former synagogue in Maison Mercier had been refurbished as a Greek Orthodox church.

Malmö. Synagogue, Y.M.C.A. and Bethania Chapel

The synagogue in the port city of Malmö, located in the south of Sweden (across the Øresund from Copenhagen), inaugurated in 1903, combines Art Nouveau and neo-Oriental elements. Fortunately, a bombing in July 2010 caused only minor damage.

Jews Hospital and Orphan Asylum, West Norwood

The new Jewish hospital and orphanage in what was then Lower Norwood (South London), designed in the style of a Jacobean mansion, opened in February 1863. Following the institution’s accreditation as a certified school in 1868, the Board of Guardians was able to place workhouse children there. In 1876, it merged with the Jews’ Orphan Asylum established in 1831 on Leman Street (Whitechapel). The facilities were subsequently extended several times. The children were evacuated during the Second World War. The orphanage then resumed its function but closed in 1961. The building was demolished in 1963.

Agricultural Workers’ Settlement in Petah Tikva

Contesting age-old stereotypes portraying Jews as incapable of interacting productively with nature, working the land held a particular symbolic significance for Zionists who envisaged that the Jews’ return to their homeland would restore them to a wholesome lifestyle from which the restrictive conditions in the diaspora had (supposedly) alienated them.

The agricultural settlement (in Hebrew, moshav) established by traditional religious Jews, in 1878, in Petah Tikva (Hebrew for “Opening of Hope”), often referred to as the mother of all moshavot, was located northeast of Jaffa. It initially failed but was reestablished in 1883 with funds provided by Edmond de Rothschild. Petah Tikva gradually evolved into a major Israeli city. The Keren Hayesod (Foundation Fund) was a fundraising organization established by the World Zionist Congress in 1920.

Rome, Tiber Island Synagogue

The (non-Jewish) architects Vincenzo Costa and Osvaldo Armanni designed the Great Synagogue, which was inaugurated in 1904 and survived the German occupation, on the understanding that classical Jewish architecture had merged Egyptian, Assyrian and Hellenistic traits.

Synagogue in Sélestat/Schlettstadt, France

The synagogue in Sélestat/Schlettstadt, designed by the municipal architect, Alexander Stamm, and inaugurated on September 3, 1890, caused some controversy because it was the first in the region with an organ. Destroyed by the Germans, the synagogue was reconstructed after the war (though without the dome).

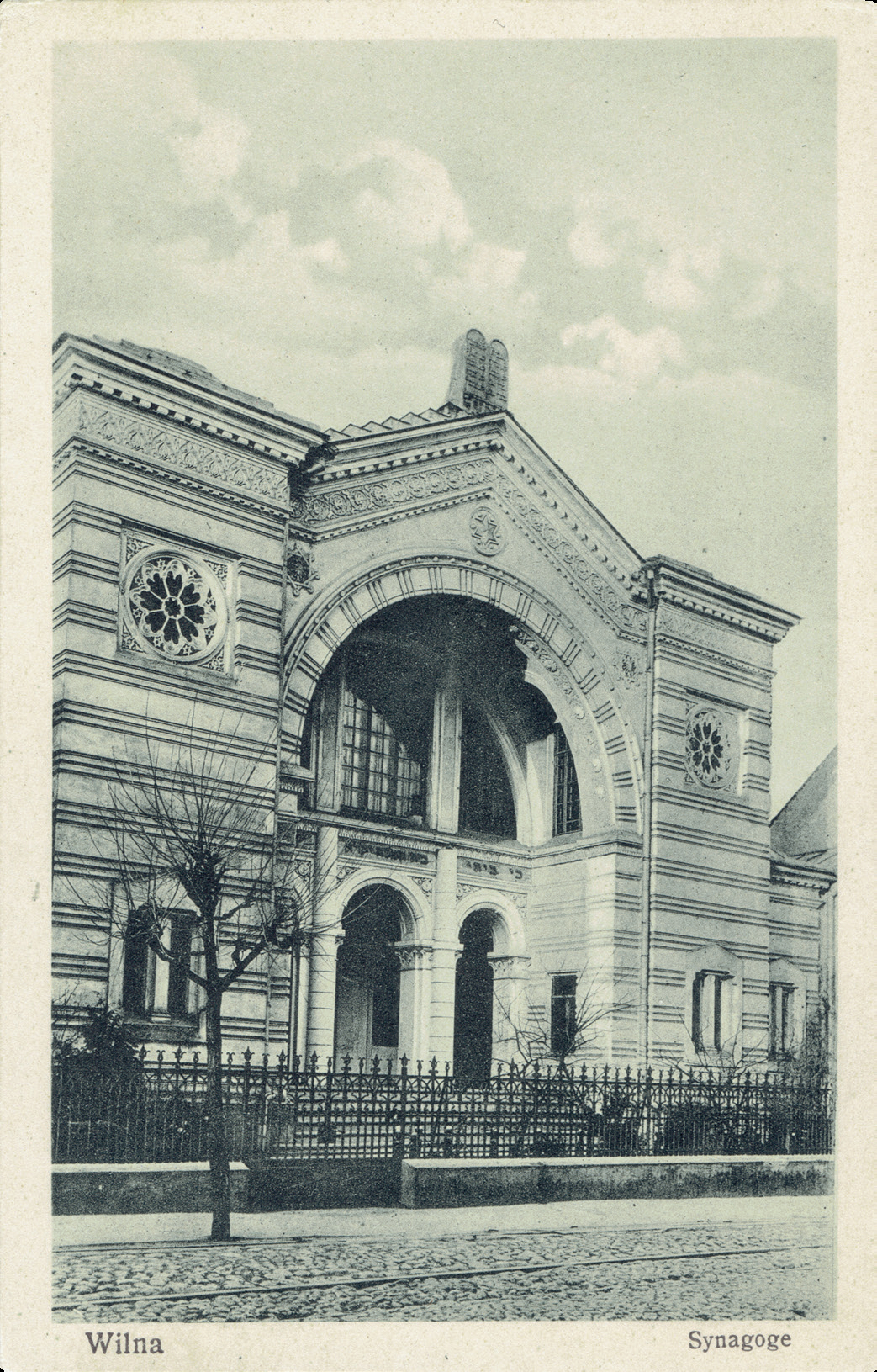

Vilna Synagogue

From the late 18th century until the Shoah, Vilna (now the Lithuanian capital Vilnius) was one of the most important centers of Jewish civilization. It was a bastion of both the so-called misnagdim, the rabbinic opponents of Hasidism, and the maskilim, the adherents of a distinct Jewish brand of Enlightenment. The Choral Synagogue, designed by Daniel Rozenhauz (1871–1941) and inaugurated in 1903, served the maskilic community. Restored in 2010, it has since been used by the Jewish community again. Rozenhauz was one of the 40,000 Jews massacred by Einsatzgruppe B on the outskirts of the city in the woods of Ponary. It was this massacre that opened the eyes of many Jewish activists who subsequently took up arms against the Germans.