One of my favorite papers by Angela Davis is “The Legacy of Herbert Marcuse,” which she originally gave as a talk at a 1998 conference held at UC Berkeley. In it, she explores the emancipatory power of utopian thought and the relationship between historical memory, philosophy, and radical social movements, particularly as they relate to Marcuse’s work as a critical theorist.

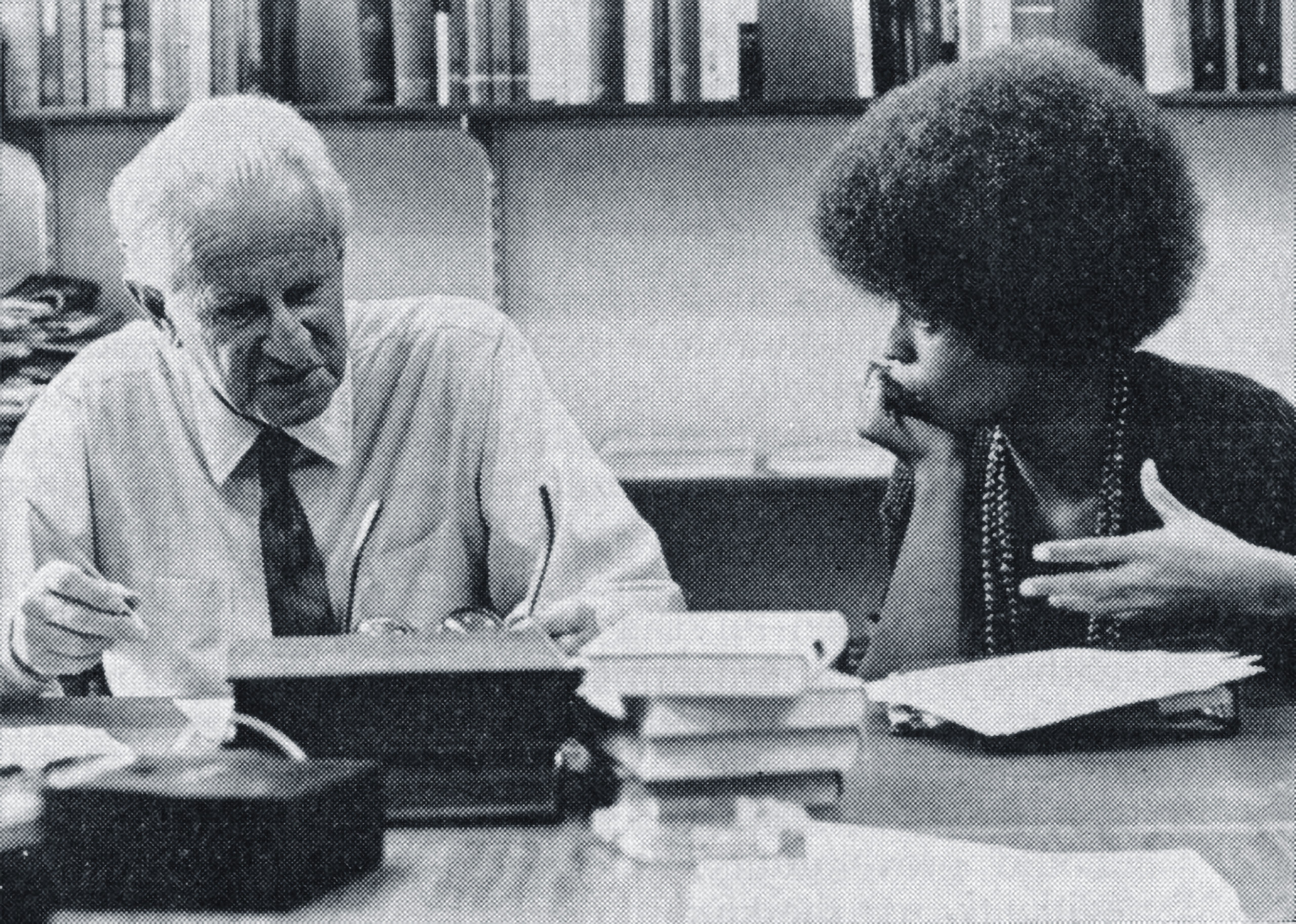

Herbert Marcuse, a German Jewish academic whose career was temporarily spent in exile during Hitler’s rise to power, was Davis’s mentor when she was a graduate student at UC San Diego in the late 1960s.

Davis credited Marcuse, during the 1998 UC Berkeley conference, for teaching her that she “did not have to choose between a career as an academic and a political vocation that entailed making interventions around concrete social issues.” She spoke to his “willingness to engage so directly in [the] antifascist project in the aftermath of World War II,” a project that she said would help him to one day conduct influential research on political violence outside of pre- and post-war Germany. “Precisely because he was so concretely and immediately involved in opposing German fascism,” Davis began, “he was also able and willing to identify fascist tendencies in the U.S.”

Marcuse engaged in extensive research on German social stratification, public policy, and political party formation in the Weimar Republic and Nazi Germany, as well as other aspects of German political life that gave insight into the rise of Nazi ideology. As explained in Secret Reports on Nazi Germany: The Frankfurt School Contribution to the War Effort, the ultimate goal of Marcuse’s research was to develop “denazification” policies aimed at restoring liberties to Germans that are required for reconstructing their society in a democratic form.

Of course Davis herself was fluent in radical thinking. Davis, who has spent many decades in the public eye as an author, activist, organizer, educator, and vocal prison abolitionist, is a theorist whose work helped change narratives about crime and punishment under global capitalism. One of her most influential books, Are Prisons Obsolete?, encourages readers to reimagine a world without a need for jails and prisons, a world in which everyone actively works to eliminate the conditions of possibility for harm against others. Many of her other books critically analyze how socially constructed features of the world like race, class, and nations impact our daily lives and perpetuate cultures of domination.

Even though her work and research is heavily informed by her academic studies, her life experiences outside of the academy inform her work even more. From her 1970s incarceration and trial that marked a pivotal time in the Black liberation movement to her Vice Presidential run in the 1980s on the Communist Party ticket and beyond, Davis’s career cannot be summed up neatly, so I highly recommend that people interested in learning more read her autobiography and other published works.

In my own graduate research, I’m interested in drawing connections between Marcuse’s denazification work and Davis’s decarceration work in an effort to highlight the importance and power of utopian thought.

To me, utopian thought is what happens when imagination meets strategy. Utopian thought is world-building rooted in reality. Utopian thought is the act of mapping new visions of what could be by starting right where you are and allowing yourself to ask, “What if?” It’s not letting go of reality in the name of a possible future of fantasies made real. It’s embracing reality as it really and truly is and using it as a “How Not To Live” guide to building a better world.

Put simply, the ultimate aim of my research is to advocate for the act of radical thinking. It’s what Saidiya Hartman and Stephen Best describe as “embracing the limited scope of the possible in face of the irreparable.” To me, active opposition to violent systems — in both practice and theory — involves using our imagination to build new worlds. It involves creating resource guides that help us and other people navigate uncharted territory.

The idea of utopia is often shrugged off as wishful thinking. Fantasies. Dreamlands. Utopian thinking is often thought of as a waste of time and energy. An exercise in futility.

I wholeheartedly disagree.

Davis’s prison abolitionist theories and Marcuse’s denazification policy theories represent forms of radical utopian thought that serve as prime examples of what it looks like to think outside of the confines of violent, repressive systems. Their work radically imagines new ways of co-existing and navigating intersecting systems of oppression.

Consider, for instance, people around the world who are community-building and creating spaces for healing and power reclamation against all odds. Whether it’s participatory budgeting projects in chronically disenfranchised neighborhoods that address people’s needs on their own terms, food scrap “microhaulers” in New York City turning food waste into a resource to restore soil health while reducing emissions and revolutionizing local waste management, or people turning empty lots into tiny food gardens to combat hunger in their communities, there are sources of hope and inspiration to turn to in the midst of despair.

That’s not to say that constantly fighting for our lives and using what little energy and resources we have to survive is something to romanticize or celebrate. The point is that we can radically imagine new ways of co-existing. New ways of navigating violent systems together. New ways of actively opposing the forces that seek to extinguish our light and stunt our growth.

During this time of ongoing global crisis and catastrophe, sources of hope and inspiration are not completely out of reach — even if it seems that way. Communities around the world are working together to come up with tangible solutions to complex problems, often relying on their imaginations to get creative about dismantling systems designed to harm and silence us.

These acts of opposition may seem small compared to the broad, structural changes we need to create the conditions of possibility for global justice. But even a tiny seed can grow a forest.

Every time I reread the radical utopian thought of Marcuse and Davis, I’m reminded that new worlds are possible. Then I look to the countless people in my community working tirelessly to bring about change and I’m reminded that seeds are being planted all around me. I’m holding onto that vision of growth.

Image of woman in header by Lorena Scintu / EyeEm / Getty Images

How I Keep Calm is our series featuring different ways people manage anxiety. We’ve slightly reframed that to How I Have Hope, in light of, you know, everything. If you have a pitch for this column, please e-mail submissions@heyalma.com with “How I Keep Calm” or “How I Have Hope” in the subject line.