In September 2021, we announced the cohort for the second year of the Hey Alma College Writing Fellows program. Over the last year, we’ve met to discuss the ins and outs of digital media while learning from them about Jewish life on campus and the meaning they find in their Jewish identities. As the school year winds down, we simply cannot let their fellowship end without bragging about their work and accomplishments. (We are Jewish, after all.)

Below is one article from each of our fellows who wrote for us this year (picking just one per fellow was truly a feat!). Though they range widely in subject, from pop culture commentary to essays on inclusivity, all of these pieces are written with tact, poise and journalistic integrity.

You can click on any name to see the author’s page and all of the fantastic pieces they’ve worked on all year. And if you’ll be in college next year, stay tuned for information on next year’s Hey Alma College Writing Fellows Program.

* * *

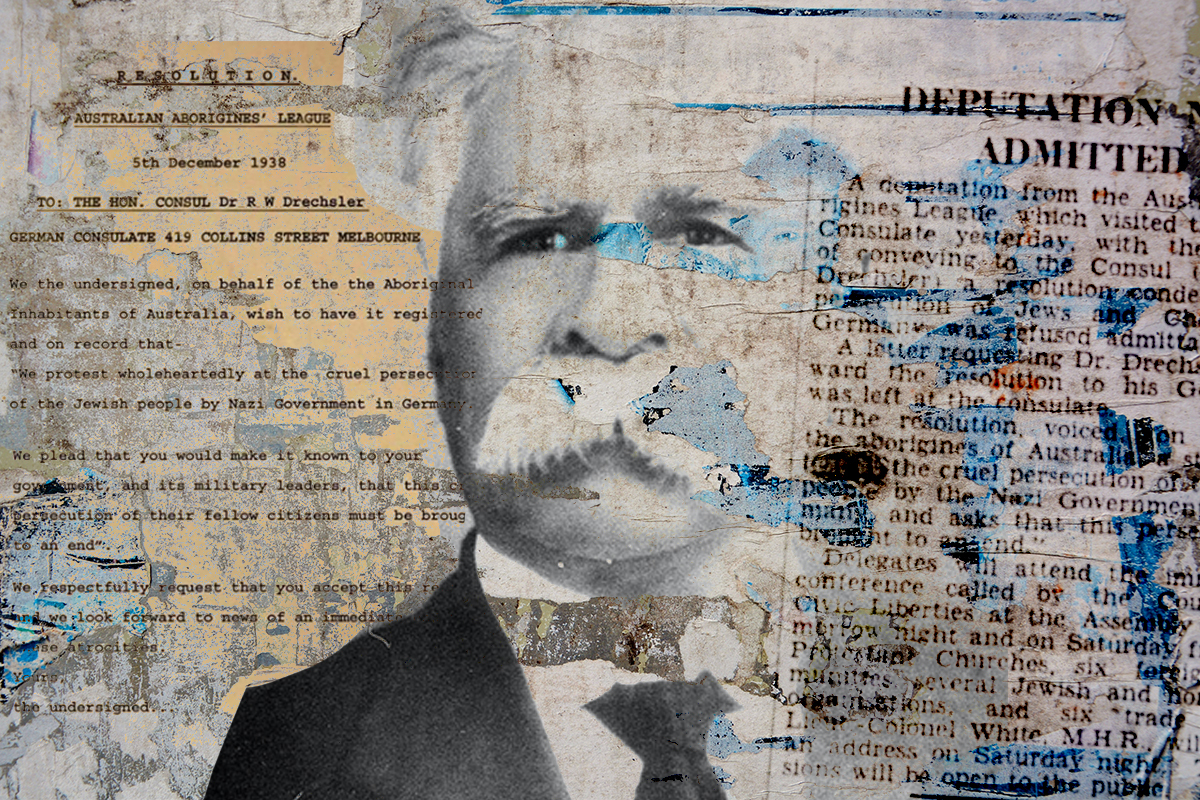

Tahlia Bowen on why Jews everywhere must stand up for the rights of Indigenous Australians.

“On December 6, 1938, the Australian Aboriginal League embarked on a 10-kilometer march across the streets of Melbourne, Australia. Formed two years earlier by Yorta Yorta Elder William Cooper to advocate for Indigenous rights, the League had an abundance of reasons to protest. Despite inhabiting the continent for over 60,000 years, in 1938, Indigenous Australians were yet to have citizenship rights extended to them, were denied the right to vote in federal elections, and faced the omnipresent threat of paternalistic, state-initiated attempts to displace their children. Yet on this summer evening, the League took to the streets to protest the persecution of a different marginalized group, a community they had never met: German Jews.”

* * *

Sophia Chanin‘s investigation into what, if any, historical connection Jews have to weed.

“This is a thought experiment. Writing a Jewish history of weed, I have realized, is really about imagining a Jewish history, period. There is so much we do not know about our origins. In this gray area of self-knowledge, perhaps weed presents an avenue for us to connect with the sensations our ancestors felt. Did they delight in dates and pomegranates? Did the seeds burst unrelenting sweetness in their mouths as they spoke the ancient languages we will never speak? Did they have extraordinary, weed-enhanced orgasms as they created the children who would become our ancestors, too?

How did our ancestors experience God? How did they reach for transcendence? If they smoked weed, why didn’t they tell us about it?”

* * *

Jane Godiner on Monica Lewinsky’s unmistakably Jewish redemption story in “Impeachment.”

“As the series has progressed, I have also noticed that its recurring themes have a great deal of overlap with Jewish cultural values. From as soon as Lewinsky’s character receives her subpoena, her anxiety is remarkably counterbalanced with courage. As much as neuroticism has taken the form of an ugly and pervasive stereotype of the Jewish community, so has the idea that Jewish people are motivated — both historically and culturally — to trudge forward in the face of adversity.”

* * *

Jamie Guterman on how the anxious Jews of “Survivor” make her feel seen.

“While watching the Jewish personalities play out on “Survivor” is always fun, relating to the players had a deeper meaning for me. Ultimately, Fishbach, Klein, and Shapiros’ clumsy and anxiety-inducing personalities helped me, an incredibly neurotic Jew, come to terms with my own anxiety. I’ve often viewed my anxiety as a tremendous roadblock. Type A and nervous, I’m always thinking two steps ahead, overthinking to the point of mental exhaustion and inertia; I feel like a klutz packaged with some strange combination of worrier and goofball. Ultimately, my constant unease has kept me from taking risks and enjoying daily social interactions with friends. However, the Shapiros and Kleins of “Survivor” embraced their anxiety. They used what seemed like weaknesses (insecurities and overthinking) as strengths (self-deprecating humor and crafty gameplay) to make allies and go far in the game. In addition to being neurotic, they were also unapologetically emotional and goofy. Rather than letting those traits stop them from excelling, they capitalized on them and succeeded.”

* * *

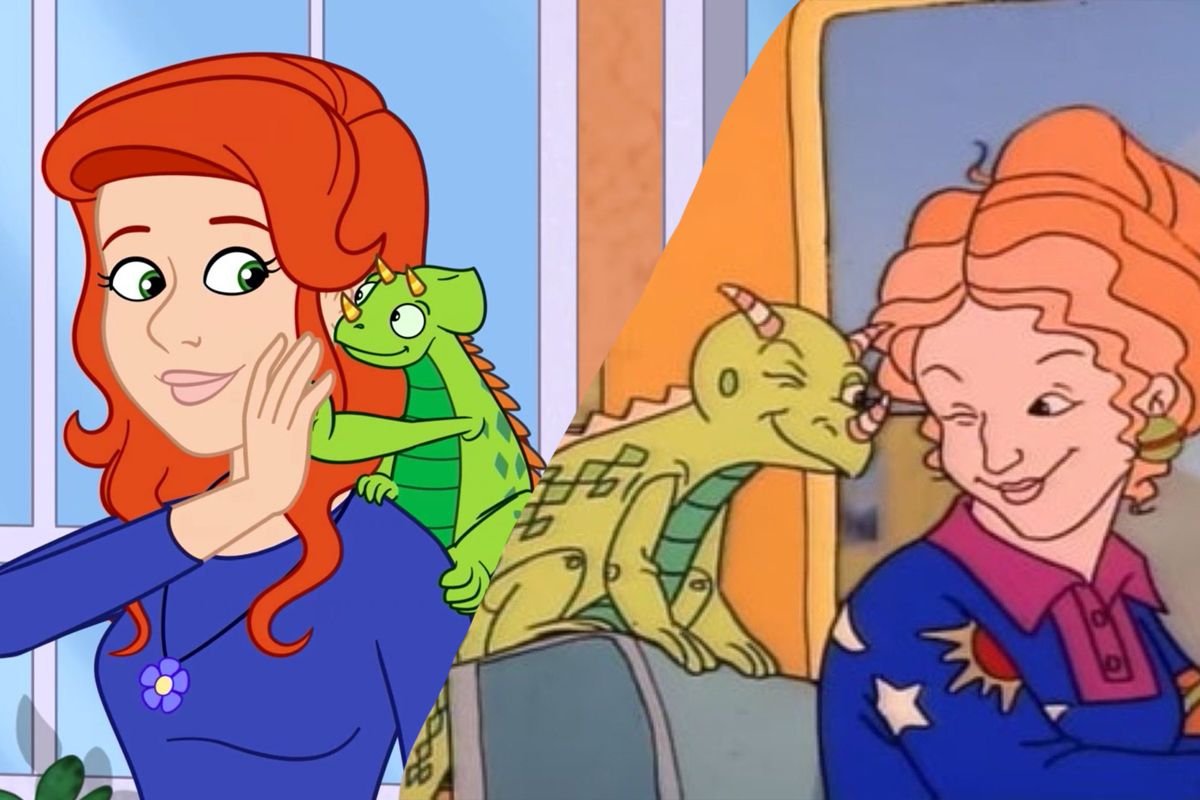

Rachel Hale‘s exploration of whether or not the “Magic School Bus” reboot made Ms. Frizzle less Jewish.

“While the reboot first came out under the name “The Magic School Bus Rides Again” in 2017 on Netflix, complete with modern animated characters and an electric theme song rendition by Lin-Manuel Miranda, the Ms. Frizzle controversy started gaining renewed traction this month, with many fans taking to the internet to express their outrage over the makeover-gone-wrong.

One user wrote on Twitter, ‘Netflix really was like ‘Ms. Frizzle but not Jewish,” with another reminiscing that ‘when i was your age, Ms. Frizzle was a Jewish lesbian.'”

* * *

Tal Israeli on being tired of feeling tokenized as a Mizrahi Jew.

“As Mizrahi Jews, we are happy to share our grandmothers’ recipes, our native tongues and invite you to dance to incredible music with us. It is crucial that non-Mizrahi Jews be made aware of these traditions and the rich diversity of culture within the Jewish community. However, events meant to cater to our needs by simply offering our foods and playing our music are not enough by themselves. We need you to do the work to invite us in every day of every month, on all occasions.

We need American Jewish organizations to go deeper into what Mizrahi history in America has been like, and we need you to actively work for a future in which we are not tokenized and exoticized. We need you to create space for Mizrahi and Sephardic Jews at the main table, not a separate one adorned with different food and a colorful woven tablecloth to be taken in with awe. Important work remains needed to be done to include diverse Jews from a variety of backgrounds, and Mizrahim must not be forgotten or their demands left unanswered.”

* * *

Ilana Jacobs on why Rosh Chodesh groups need to be more inclusive and go beyond cis-straight female narratives.

“For me, reinterpreting Rosh Chodesh means talking about gender dysphoria along with body dysmorphia. It means reading about the difficulties of marriage from trans rabbi Joy Ladin and the rewriting of Lilith beyond Adam from lesbian theologian Judith Plaskow. It means asking how mikvahs can be healing and affirming outside of Niddah, the traditional ritual after menstruation. It means acknowledging that trans and queer voices are not an addendum; they are central to the story.”

* * *

Mara Kleinberg on the Jewish coming-of-age story central to “Licorice Pizza.”

“It is rare to find representations of young Jewish women onscreen whose Judaism is not only acknowledged, but also essentially characterizes who they are. We recently had “Shiva Baby”; further back, there’s Barbra Streisand’s portrayal of Fanny Brice, Fran Drescher on “The Nanny”… and that might be it, unless you count cartoon portrayals. Sure, we have Cher Horowitz of “Clueless” and Gretchen Wieners of “Mean Girls” as pop culture examples of Jewish women — but their Jewishness feels less deep, and they are characterized as the stereotype of a “Jewish American Princess.” Alana in “Licorice Pizza” creates a character who breaks down stereotypes and prides herself on her Jewishness, as it sets her apart.”

* * *

Alexa Kupor on why Jewish youth groups need to look past the gender binary.

“I know we can retain the unique traditions and relationships that fill us with such pride and celebration for our shared spiritual identity without simultaneously upholding a systematic exclusion. We can elect leaders, serve as role models and craft the older-younger member bonds that make our Jewish youth groups so life-changing without gender and sexual experience serving as our sole bonding tactic.

In fact, not only can we maintain our beloved circles of empowerment, understanding and innovation while opening our hearts to the elimination of gender exclusion, but we must, or we risk becoming utterly obsolete.”

* * *

Caroline Levine‘s letter to non-Jewish Jewish parents.

“My family is a beautiful blend of Jewish parents and, as I like to call them, non-Jewish Jewish parents. In the modern age, families are no longer culturally, ethnically and religiously homogeneous, and that’s OK! I firmly believe that we do not have to make them homogeneous either. One Jewish parent and one non-Jewish parent can still raise a beautiful Jewish family and their level of conversion, ethnicity or religiosity should not need to be a public detail. Modern lives call for modern definitions and there is no wrong way to be Jewish, as long as you are dedicated to the Jewish people and to Jewish traditions — even traditions as simple as baking challah once a year and calling it a day.”

* * *

Adam Possener‘s profile of a queer yeshiva radicalizing the study of Talmud.

“The session I attended looked at a verse from Berachot 17a with one translation being: ‘May you see your world, may you benefit from all of the good in the world, in your lifetime, and may your end be to life in the World-to-Come, and may your hope be sustained for many generations.’

This gave rise to a discussion on community, role models and queer elders. There was a sense that in contrast to mainstream Judaism’s emphasis on the nuclear family, queer families are chosen and forged. In this discussion I saw a room full of people who were at once so different and yet so similar to each other express love, generosity and a sense of community. Every point of view was fresh and people were so willing to learn from one another that they would applaud when someone shed light on an interesting phrase. The spirit and energy of the room was so infectious that I left the session convinced that I’d witnessed something incredibly important.”

* * *

Rachel Rumstein on “Turning Red” and the similarities between its Chinese coming-of-age story and her Jewish American upbringing.

“Mei and her mother display a particular kind of partnership that I have witnessed across not only my family, but my Jewish friends and their mothers, and my friends of immigrant families. It’s a sort of unspoken routine that gets established between a mother and her daughter — one of expectations and duty to one another, but also of equally unspoken, abundant love and adoration. It’s a dynamic created not only by the maternal bond, but by the honor and duty of carrying the tradition forward.”

* * *

Tatum Schutt on Disney’s history of Jew-coding its villains.

“Disney produces media for young minds. There are real consequences to marinating youth in antisemitic imagery that trains us to unthinkingly identify any hint of darkness or Semitic origin with ugliness and evil. I, for one, grew up with a virulent burning hatred of my untamable curls, and by 6th grade I was secretly saving money for a nose job to address my barely perceptible bump.”