A couple years ago, a young man approached me outside a Chelsea bar, getting a little too close for comfort.

“Are you really an Arab?” he asked, as if we had been mid-conversation.

I get asked this a lot, but never so abruptly, with so little prior interaction. He was clearly drunk, but also clearly excited at the notion of having spotted a fellow Arab in New York City.

“How did you know?” I said.

“The eyes,” he said. “Where are you from?”

“Israel,” I said.

“Israel,” he repeated, not quite asking a question. His brows knotted themselves in bewilderment; this was not the answer he’d expected.

“My family came from Yemen,” I added in an attempt to clarify.

It’s not the whole truth, but a watered-down version of it. My dad is a Yemeni and Bukhari Jew from Holon, Israel, and my mom is an Ashkenazi Jew from Los Angeles. My collective ancestors, in their long-standing exile, managed to cover an impressive portion of the Jewish diaspora — Yemen, Bukhara, Turkey, Morocco, and the majority of Eastern Europe. This lineage of mine — the slippery answer to the question “what are you?” — is a mouthful, so I simplified. He thought he’d found an Arab. I wanted to let him know he was right, but it’s a little more complicated than that.

Turned out, he was from Egypt. He called his friends over and told them he’d found an Arab Jew; they all cheered — the way people do after copious amounts of alcohol. For them, this was a novelty. I’ve come to love these kinds of moments — seeing the astonishment on people’s faces when they find out that such a paradoxical creature exists.

But Arab Jews aren’t a novelty at all. We fall under a term called Mizrahi in Hebrew, which literally means “Eastern,” and we’re not rare, nor endangered. Mizrahis make up over half of Israel’s population, rounding out at about five million globally, but somehow, we’ve gone largely under the radar in both Jewish and Middle Eastern narratives.

In North America and Europe, most Jews are of Ashkenazi descent. This may account for some of the lack of Mizrahi representation, but I suspect there’s more to it. The existence of the Arab Jew — the indigenous, brown-skinned Jew — has the power to crumble long-standing dogmas. For one, the idea that Jews and Arabs are inherently at odds, that one is the antithesis of the other, and that the so-called “gaps” between the peoples are so vast as to never be reconciled. These types of nuances can be uncomfortable for those who are quick to file away information into perfectly neat labels in their mind. The Arab Jew defies broad categorization.

Even many Mizrahis tend not to think of themselves as Arab. Many, including members of my own Mizrahi family, become indignant — offended, even — at the insinuation. They’ve been told the same story: Jews can never be Arabs. But in believing this, they deny themselves a part of their heritage — the thousands of years of shared history in the Levant, North Africa, and the Arabian Peninsula. The spices and foods, dances and folklore. Even the values — the hospitality and generosity of spirit, the piety and modesty of character, and of course, the hectic and often heated exchanges — all endemic to the Middle East, irrespective of faith.

When I was younger, I wasn’t interested in embracing my Mizrahi side. As the daughter of a diplomat, I’d spent my childhood split between the U.S. and Israel. But our home base was a small suburb outside of Jerusalem by the name of Mevaseret Tsion, which was originally founded as a transit camp for Jewish refugees from Iraq and Kurdistan. My classmates were a diverse bunch — Mizrahi, Ashkenazi, and many mixed, like myself. But the overtly Mizrahi kids, the ones who spoke with guttural “chets,” ate spicy sandwiches and kubeh for lunch, and blasted Mizrahi music out of their cell phones, were often branded as “arsim” and “frehot,” Hebrew terms which loosely mean dumb and trashy.

And so, for many years, I internalized this and denied my Mizrahi culture; it was easier to tuck it away, shove it in some faraway cabinet, and not risk, God forbid, being called a “freha.” I shied away from spicy condiments like zhug and amba, renounced Mizrahi music altogether, and often told those who’d questioned my ethnicity that I wasn’t “a real Mizrahi” — whatever that meant. I’d believed that in order to be taken seriously, I needed to shirk that part of my identity. I met no resistance within my own Mizrahi family, because sadly, most of them had done the same.

Five years ago, I moved to New York City. On the other side of the Atlantic, enshrouded in blissful anonymity, I began to change. Slowly, I found myself chipping away at the barriers, the prejudices that had allowed me to suppress entire facets of myself. I gave myself permission to wonder, ask questions, and reexamine the stories I’d been told.

I once took an Uber ride with a Yemeni driver. He looked like he could have been one of my uncles. I told him of my Yemeni grandmother and his face lit up. I thought maybe his grandfather knew my great-grandfather — maybe they plowed the millet fields together or chewed ghat over nargilah. We talked about Yemen, and Zion Golan and Ofra Haza, two Israeli-Yemeni singers who are still wildly popular in Yemen. He told me about the war and the famine, and I felt his pain in my bones. We parted ways with a mutual blessing, but only after he told me where to find good, authentic Yemeni food. That weekend, I went and sampled my first ever aseed, a dish my grandma had once described as the finest delicacy of her childhood. It was heavenly.

Moments like these brought me closer to home. I spent hours on the phone with my Yemeni grandmother. We found solace in one another — her, in my listening ear, and me, in her vast well of stories and the opportunity to rediscover my own story through hers.

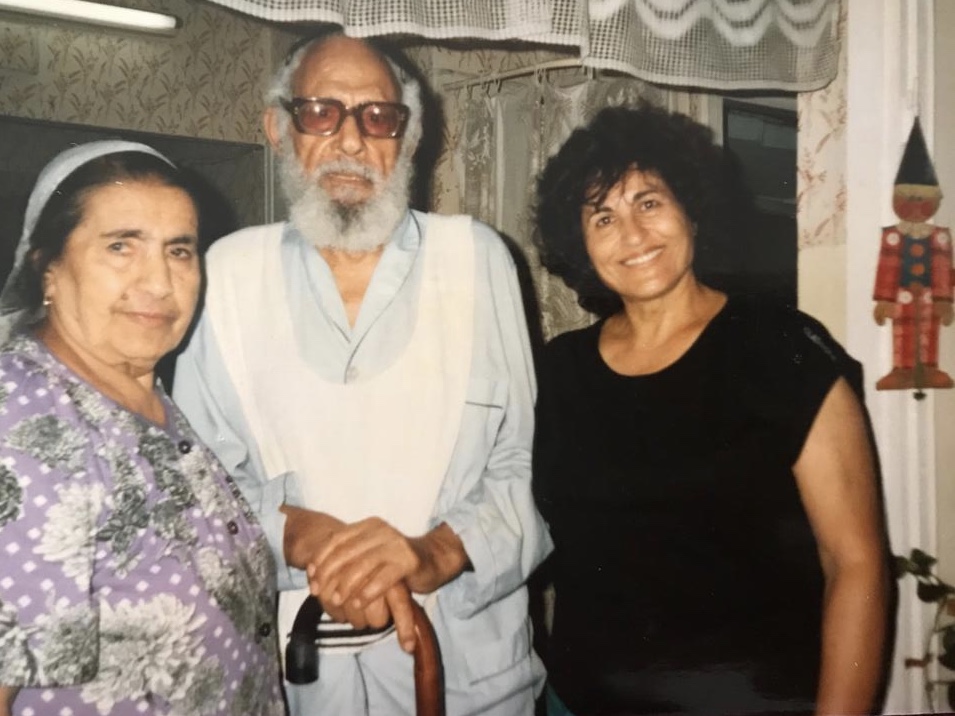

I asked her everything I could think of, and she, a magnificent storyteller, reveled in the retelling. I asked about her childhood, and about my great-grandparents, who passed away when I was young. I still remember them, how they looked so foreign to me. How their foreignness had frightened me.

My great-grandfather Yehuda had come from a small village of potters near Ibb, Yemen at the age of 14 with his two younger sisters and a donkey. He later paved roads, worked at a t-shirt factory, and then as a sanitation worker. My great-grandmother Sarah, on the other hand, had come from Sana’a, Yemen as a toddler, via Egypt. She was a deeply superstitious woman, who believed in spirits and amulets and ceremonies that could summon miracles. She worked, until her last days, as a cleaning woman.

My grandmother Ahuva grew up in the slums of Tel Aviv, in a neighborhood called HaTikvah, which was full of Yemeni refugees. Her childhood was marked by poverty, hunger, and strife, and a wealth of miracles. Everyone was poor, and everyone had faith.

During our phone calls, she’d recount the fantastical tales I’d first heard as a child. Stories of demons bearing mysterious gifts which were not to be touched. Stories of tiny women, light as feathers, who could speak with songbirds. One such woman fell off a roof and walked off without a scratch. She lived to be 100 years old, and then died in her sleep, curled up in a ball at her husband’s feet. As a child, these stories blew me away with their magic, and planted in me the earliest seeds of storytelling. As a writer, they inform what I choose to write about, and why.

When I enrolled in an MFA program in New York City, I knew these were the stories I needed to write. The stories of my ancestors, of the Arab Jews — in all their nuanced glory, with their beautiful folklore, and a richness that challenges my attempts at any kind of adequate portrayal. A part of me knows no portrayal will ever be adequate, and that’s okay. To me, all that matters is their stories be told.

Header image illustration by Grace Yagel.