There’s a new refugee crisis in Europe. One month into Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, a staggering 10 million Ukrainians have fled their homes, with 3.8 million people escaping to neighboring countries. One site of these border crossings is Siret, Romania, where thousands of Ukrainians seek shelter, aid and solutions for their futures.

Across Europe, Jews are looking for the best way to support Ukrainian refugees. To better understand these efforts, I sat down with 26-year-old Avital Grinberg of the European Union of Jewish Students. Born in Berlin but raised in a Russian-speaking household, Avital, who is now based in Brussels, recently spent five days working in Siret. She shares her insights on what it’s like on the ground, how she engages in the crisis as a Jew and a feminist and what comes next in the largest European displacement since World War Two.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Tell us a little bit about what you were doing last week.

I went to Siret, which is a Romanian town on the border of Ukraine, to volunteer. My tasks varied widely — everything from welcoming the refugees to making sure they had a ride to their first accommodation. Especially as a Russian speaker, my main task was translation. I was talking to refugees in Russian, translating our conversation into English for my Romanian friend, and then she would translate to the Romanian authorities.

How were you able to go to Siret?

I went because of the organization I work for, the European Union of Jewish Students, which is the umbrella organization of national representation of young Jewish adults across Europe. When the war broke out, we investigated ways to engage and learned that translation is the main need, especially in countries like Romania. I’m the Russian speaker in the organization, so I went to help and to bring back information on what more EUJS can do as the war continues.

What were your first impressions of the border like?

The border of Siret is such a balagan (Hebrew/Yiddish for chaos or mess). People are coming in and they don’t know whom to address or where to go, even though there are a lot of humanitarian organizations present — as opposed to the Polish border, where everyone is given a QR code that links to a map and a list of services.

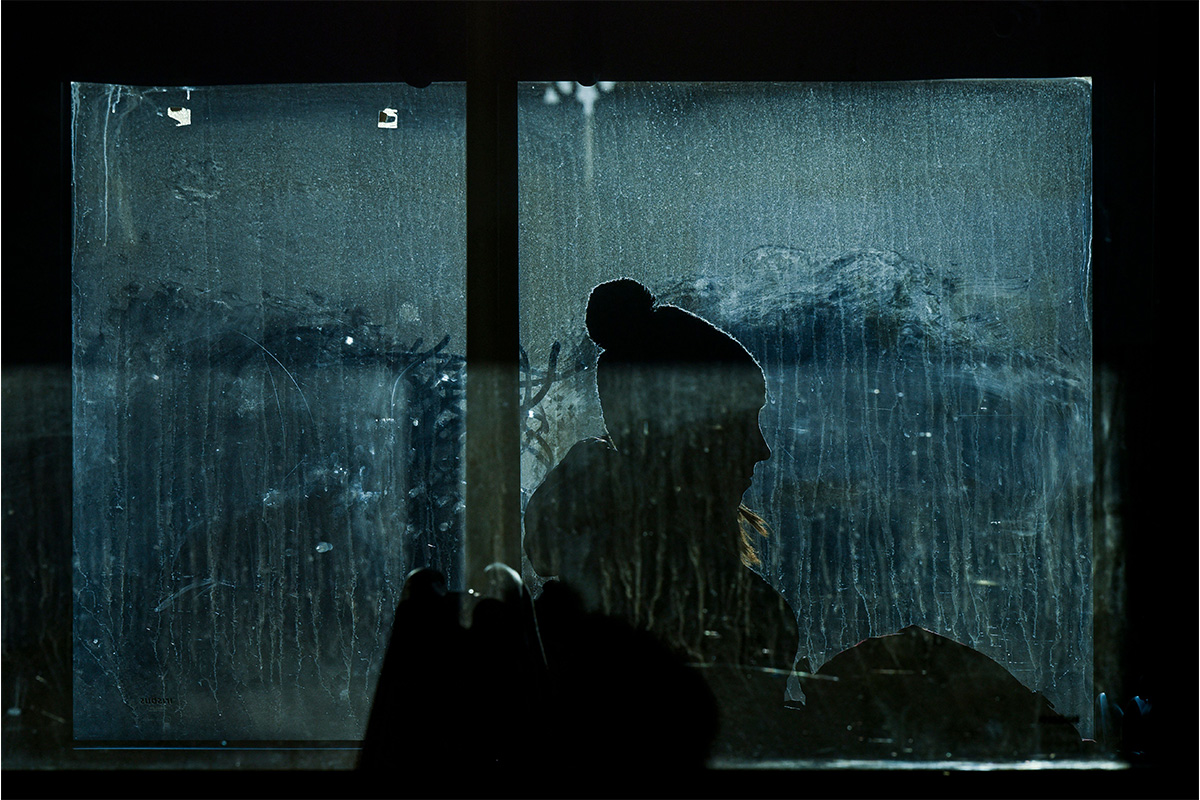

Emotionally, it felt special to be part of the moment when people finally left Ukraine — which is tragic and traumatic and sad, but I could see the relief on their faces. I was emotionally exhausted the first day. I grew up in a country of peace; my understanding of war is so minimal.

What is the Jewish presence like on the border, both in terms of Jewish refugees and the organizations on the ground?

The Jewish organizations are doing an impressive job. JDC, the Joint Distribution Committee, has a huge tent serving all the refugees. There’s a highway filled with humanitarian organizations’ tents, and the first one is the Jewish one. Which doesn’t matter practically, but it’s —

Symbolic?

Symbolic, yeah. They had everything a person might need, and I got to speak to so many people.

In terms of Jewish refugees, we helped Jews arrange travel to Israel or somewhere else in Europe. That was hard because I started thinking about the people who don’t have easy access to a new home, or to such personalized care. But it’s the idea of kol yisrael arevim zeh bazeh (all Jews are responsible for one another), right?

Plus, the majority of the people that I helped to find housing or transportation were not Jews. There were tons of opportunities outside of the Jewish tent, but they needed help finding them. And of course, whether they’re Jewish or not doesn’t matter in that moment.

Because of the law requiring all Ukrainian men age 18-60 to stay in the country, the majority of refugees crossing the border are women. How did that impact the type of help needed?

I’ve been thinking about this war through a feminist lens. This is a war executed by men, but I believe that women carry a burden that many don’t recognize. The refugee women I met weren’t part of any decision-making processes — not in the war and not really in the humanitarian organizational system. But they are the ones keeping themselves and their children alive, ensuring security and a future for their families and ultimately for Ukraine.

Western Europeans sometimes dismiss Eastern European women. They’re often viewed as submissive, dependent, and partnership-focused. But in this tragedy, we now see their resilience and bravery. This war might be a learning experience for them, but we’re the ones who need to learn from their strength.

And from a practical standpoint, the women crossing the border needed emotional support. They needed a hug. They needed assistance gathering supplies they may have left at home, especially hygiene products. We were able to give out flowers on 8th of March (International Women’s Day), and it meant a lot to give a moment of dignity, of feeling seen and appreciated. It’s easy to forget how important those basic human feelings are in times of crisis.

What are you hoping to do next in response to this crisis?

We’re looking into how we can ensure Ukrainian Jewish students have access to Jewish life in Europe, if they want it. A big step is also advocating for their easy access to European universities, because one of the biggest problems they will face is university bureaucracy, transfer credits, housing and so on. We know it’s going to be very important, and we hope to be a key player in that effort. We want them to be best equipped for their future, whether it’s in Europe or back in Ukraine.

How has your personal experience changed the way you see the world’s response to the war?

Protestors all over the world scream “Slava Ukrainy” — glory to Ukraine. Generally, I love seeing this solidarity and awareness: Not many war crimes are given this level of attention. But I wish people would also say “Slava Aliny,” a woman I met who gave her daughters the freedom to see their escape as an adventure. “Slava Tatjany,” who went back to Siret days after she herself escaped to help other refugees. “Slava Nastiy,” who is a model to her whole family of how education, intelligence and determination can help get you out of misery. We can, and need to, support Ukraine and celebrate the heroism of Ukrainians. But nationalism is not a good weapon against nationalism.