Anyone who speaks to me in the days before my trip to Poland knows I am not looking forward to it. It’s been on my bucket list for ages, yes, but now it’s November 2023 and the last month has simply depleted my patience for stories of Jewish suffering. A weekend of immersion in the most tragic, violent period of our history seems like the worst idea ever.

But the trip is booked. My grandma has flown to meet me in Europe, and the chance to do this together is unique. I know that. On this chilly Saturday morning at Warsaw East Station, as we decipher the Polish signs and board what I am utterly convinced is the wrong train, I try to leave my reservations behind.

One word I do recognize greets us on a wooden sign when we arrive two hours later: Sarnaki. A tiny village, barely a few blocks of houses surrounding a central square. My family’s home for generations, up until they were forced to flee in the wake of the Second World War.

Rafal waits for us at the small, deserted platform. Who exactly is Rafal is a complicated question to answer. He is forty-something years old. He lives in Warsaw. His parents and grandparents lived in Sarnaki, in a house he now uses on weekends. He is Polish. He is not Jewish. No one knows exactly how, but a few years ago he got my grandma’s email. He reached out and explained that one of his hobbies is collecting historical data about the village and helping preserve Sarnaki’s past through education, restorations and contact with the families of survivors. Meaning: us. We’ve been in sporadic contact ever since, exchanging stories, photographs and translations. Today, he and his twelve-year-old son, Yurek, have offered to show us around. We climb into their car and, at first, travel in silence. I can’t think of anything to say to them.

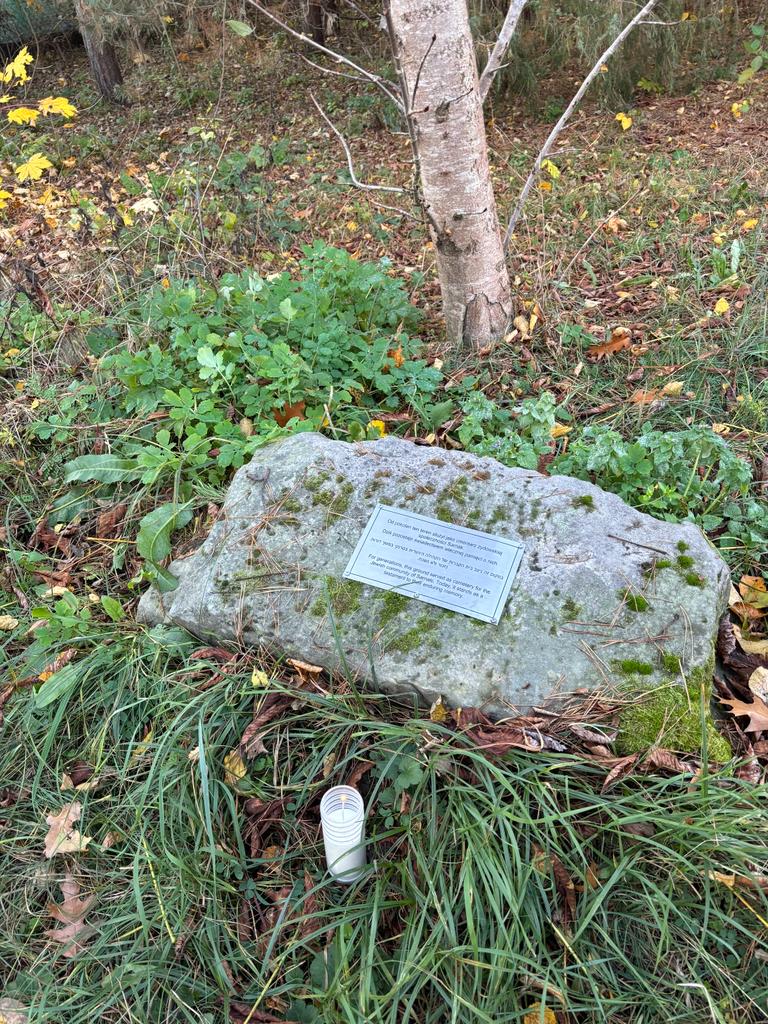

The first place we visit is the old Jewish cemetery. It’s nothing but a clearing now, since the gravestones were used by the Nazis for road-building, but Rafal explains he and a few other volunteers came together to clean it up a few years ago. They restored the two ancient matzevot they did find, and when my mom was here earlier this year, she brought a plaque to commemorate those buried there. Rafal has put it up by the entrance.

As we wander around the village, Rafal and my grandma each speak to me in a different language. Still, somehow, they complete each other’s sentences, like they’ve seen the same movie and know the same characters. Every time one begins a story and I start translating, the other interrupts me with the ending. Rafal even uses Hebrew and Yiddish words sometimes. We pass forests and barns, and he tells us about people who helped hide their Jewish neighbors there. I begin to ask questions. Yurek and Rafal also become more comfortable. They ask us about Argentina and other former Sarnaki residents that we know.

Our last stop is Rafal’s house. It’s a hundred-year-old farm house that belonged to his grandparents. It looks exactly like my great-grandparents’ houses looked, before one was bombed and the other demolished. Inside, Rafal’s wife, Monica, and his daughter, Olga, are waiting with a traditional Polish lunch that looks straight out of a storybook painting. A plate full of cheese and mushrooms they picked from the forest, just like my great-grandma used to. They timidly ask us if we are kosher, and when we say no, they bring a traditional sausage from the kitchen, which they add to the feast. We sit down, try the food (indescribably delicious) and begin to talk.

It’s strange. It is difficult to converse cheerfully about the trivialities of Jewish life in Sarnaki without banging your head against the fact that this life no longer exists. That many Polish people did nothing, or worse. That every story I’ve heard about this village ends in heartbreak. How can I explain this to these kind, lovely people, without seeming offensive? Our bond with them is built on a precarious balance. Being in Poland is like that, all of it. You can walk across all of Sarnaki, across the entire country, with your heart in your throat.

But next to me sits a man dedicated to protecting the history of families like mine in his town. And when I ask Monica how she and her husband know so many words in Hebrew, I discover that she is a guide and educator at the Jewish history museum in Warsaw. And we chat for almost two hours, about religion and food and immigration, and they understand everything. They tell us about the Jews currently living in Poland and how Polish people today learn about the Shoah. We talk about Argentina and laugh about our political problems because that is another thing we have in common. We make jokes, tell funny anecdotes, and my grandma laughs at what they say even before I get to translate, and they laugh at what she says in a language they’d never heard until today, and we don’t really know how, but we understand each other. They try Argentinian alfajores and we try a Polish sweet called ptasie mleczko. When we have to leave to catch our train, I don’t want to. There is no trace of the morning’s discomfort. We hug each other goodbye.

Before we go, Rafal and Yurek make a suggestion: It’s the weekend of the Day of the Dead, they explain, and the tradition is to light candles next to the graves. They know it’s not a Jewish tradition, but if it’s okay with us, they want to light a candle in the cemetery, next to the plaque. We say yes. We all return to the cemetery, light the candle and stay a while.

Of course, in the grand scheme of things, this changes nothing. This is not an entire country. Not even an entire village. Just one family. One candle. But in a place like Sarnaki, where my family encountered the worst kind of antisemitism, something like this can also happen. Something like the lunch we just had can happen. If my great-grandparents saw us sitting at that table, laughing with the Polish neighbors, perhaps they wouldn’t believe it. But these days, I am trying hard to believe that the world can be this, as much as it is everything else. That someday, even the darkest stories can end in dialogue, understanding, and, dare I say it, peace. Yes, it changes nothing. But it changes something in me.