“V’higgad’ta l’bincha” — “and you shall tell your children” — is the principle at the heart of Passover. It’s no wonder that, as a writer, my favorite Jewish holiday is one where we famously gather to read a story, when Jewish people of every generation are meant to look back at where they come from and walk a mile (or 40 years) in the shoes of their ancestors. Three years ago, around Passover in 2020, “V’higgad’ta l’bincha” took on a different meaning for my family. That year, the question of what was different that night from other nights seemed almost comical in its failure to convey how unrecognizable the world felt at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. To ask what wasn’t different would have felt more appropriate. But amidst the uncertainty and gloom of our virtual seder, another story of liberation was beginning its journey onto the page.

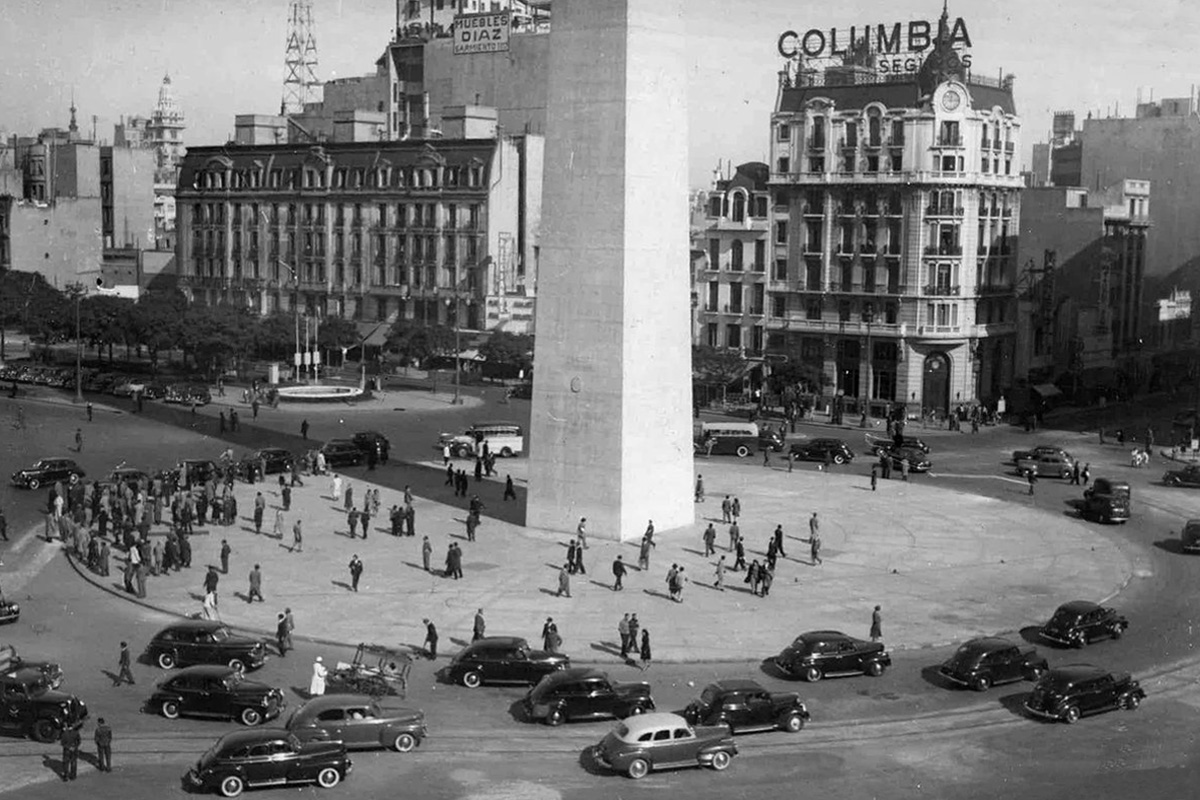

Three years later, my Bubbe Jane’s book, “Historias Tejidas” (“Knitted Histories”), has finally been completed, and an advance copy might just find its way onto our seder table alongside the haggadah. The book tells the story of her parents, Chaim and Rivkeh Karszenbaum, in the years leading up to, during and after the Shoah. It follows them in Sarnaki, the Polish shtetl where they were born and raised, and then out towards Siberia where they were deported by the Soviets in 1940. It also chronicles the family’s journey across Europe once the war ended, which took Chaim, Rivkeh and Jane, then a baby, through Russia, Poland, Germany and France before they landed on a ship to Argentina. Finally, it covers their first years of life as immigrants in Buenos Aires. This was a story that my grandmother had always dreamed of putting onto paper, but she’d always been busy or tired or, frankly, a little bit scared. But during the pandemic, she enlisted my help as an editor and finally set out to write.

Over the course of three years, my grandmother worked hard at capturing this story in all its complexity. We had meetings, beta readers and many, many revision rounds. This was the first literary work I ever got to edit on my own, after having been on the receiving end of feedback as a writer for most of my life. Editing taught me no small amount of lessons about writing, including how terrifying and rewarding it can be. It also encouraged me to learn about my family’s history in more depth than I ever had before. As we wrote about my relatives, their personal anecdotes and the details of their lives, they became fleshed out in my head as more than just names or black and white pictures.

The effect this process had on my grandmother was even more extraordinary. My Bubbe Jane is the coolest person I know. She is unflinchingly honest and sensitive, and she has a keen eye for detail — all of which makes her a superb narrator. She knows so much about Jewish history and traditions that even her rabbi has told her, repeatedly, to chill. She has a vast supply of wise quips and funny anecdotes that spans decades and carries not just her own history, but also her parents’ and grandparents’.

My whole life, she has been a channel for other people’s voices, always telling me stories about our family or sharing lessons from different thinkers and artists. In this book, however, she got to put her own voice and story in the spotlight.

I remember countless conversations during which I, along with our other collaborators, nudged her to highlight her own experiences, thoughts and feelings, rather than just narrating the facts of her family’s history. Thus the book, which began exclusively as an account of the Karszenbaums’ journey from Poland to Buenos Aires and was meant to finish with their arrival, ended up extending far beyond that: It includes my grandmother’s primary school anecdotes, her memories of Jewish holidays spent with her relatives, her time at the tnuah (Jewish youth movement), her teenage years and everything that came afterwards. This second portion of the book doesn’t just brilliantly portray the experiences of Jewish immigrants in Buenos Aires in the first person. It also serves as a way to humanize her as a character in her own story — to place her at the center of what she wrote and allow all her readers, especially those who are closest to her, to know her better.

In the book’s epilogue, my grandmother explains: “I wrote this book in order to leave behind a testimony for future generations about the life of my parents during the Shoah and their capacity for resilience. Let whoever reads it know how they overcame difficulties and raised a beautiful family, passing on moral values and Jewish traditions. This is their legacy… I feel blessed doing my Cheshbon Hanefesh, the balance of my life…. This is the Jane who wrote this book; who experienced the pain of her loved ones, carried their history, their tears and their silences, and saw them reborn from catastrophe with dignity, effort, will and melancholy. Who felt the need to be their voice and their memory.”

If I may, as an editor, make one last addition, I would also say that in bringing their voices to paper, my grandmother found her own.

By writing this book, my grandmother was able to confront her family’s past, gain closure and build a lasting tribute to her parents while showing the younger generation of our family, who did not get to meet them, a piece of where they come from. At this Passover and every Passover to come, I will be proud to have been a small part of getting this story told. It’s a kind of personal haggadah for my family which, much like the original, covers some dark chapters of our history along with our hope and our deliverance.