Intersectionality

Intersectionality and the Israeli-Palestinian debate

Part of: Hey Alma’s Guide to the Israeli-Palestinian ConflictIntersectionality, which leaped from academia to the mainstream in the past decade or so, is the theory that no form of discrimination (such as racism, sexism, and classism) can be separated from any other, and that all marginalized individuals or groups must be allies in each other’s struggles.

Intersectionality has also become a sticking point in the debate over the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, especially in spaces where some activists insist that support for Zionism, or just support for Israel’s current government, cannot coexist with the struggle for social justice, and particularly, feminism.

That’s a lot. Let’s unpack it.

What exactly is intersectional feminism again?

Intersectional feminism, coined by scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989, posits that each layer of an individual’s identity can help us better understand how and when they experience power and oppression.

American activist Ai-jen Poo explains it this way: “When you are a black woman or a queer, immigrant woman, your experience of violence isn’t ‘gender inequality plus racial inequality,’ but it’s all of those things at once.”

According to Crenshaw, “Feminism investigates and challenges the forces that cause injustice or inequality. However, those forces are not the same for all women, because forces of oppression (sexism, racism, classism etc.) intersect.”

In other words, if you’re a black woman, or a queer woman, you’ll experience blackness, queerness, and womanhood — as well as racism, homophobia, and sexism — differently than someone who doesn’t share your multiple identities.

So where does the Israeli-Palestinian conflict come in?

To some intersectional feminists tuned into the Middle East conflict, they see a serious power imbalance between the Israelis — who have a state, a functional democracy, an active military, and abundant social services — and Palestinians, who live under occupation.

As long as Israel continues this occupation, some argue you cannot be a feminist and a Zionist: To do so would be to actively oppress Palestinian women, which cannot be a feminist cause.

Wait, so can you support Israel and still be an intersectional feminist?

It depends on who you ask.

Linda Sarsour, a prominent Palestinian-American activist and co-chair of the Women’s March, has stated, “Is there room for people who support the state of Israel and do not criticize it in the movement? There can’t be in feminism. You either stand up for the rights of all women, including Palestinians, or none. There’s just no way around it.” Note: While some took this to mean that Sarsour believes you can’t be a feminist and a Zionist (which is how the Nation phrased it in their headline), others argued that she is differentiating between unflinching Zionism and critical Zionism, meaning you can be a Zionist but still critical of the occupation and other Israeli policies, and therefore a feminist as well.

After that statement from Sarsour, many self-proclaimed Zionists and feminists wrote op-eds explaining why they believe the two identities are not incompatible. In the Forward, Brad Lander wrote an article titled “I’m a Zionist and a Feminist. I Stand With Linda Sarsour.” The Anti-Defamation League ran a letter by Carol Nuriel, concluding with, “As an Israeli committed to fostering a more equal and tolerant society — one in which Arab, Druze, Bedouin, LGBT, secular and religious, and Jewish and Palestinian women have an equal place — I am proud to say that I am both a Zionist and a feminist.” Even actress Mayim Bialik chimed in.

Let’s switch gears.

Okay!

What’s the deal with Israel and white supremacy?

Because many of the Jews they encounter are from Western and Eastern European backgrounds — and many early Zionist leaders were themselves European — some activists characterize Israel as an imperialist white supremacist state, and therefore, say that resistance to white supremacy must include resistance to Israel. Many black power leaders, like Stokely Carmichael (later known as Kwame Ture), emphasized anti-Zionism in solidarity with the anti-colonial struggles of the world.

Israel’s supporters tend to refute this categorically, noting that the majority of Israelis have roots in North Africa, Ethiopia, the Caucasus, and nearly every Middle Eastern country that surrounds Israel. Israel is itself a haven, they note, for Jews expelled from countries for racial and religious reasons.

Iranian-born American academic Sharon Nazarian explains why she thinks this de-contextualization of the conflict is not great, arguing it presents the conflict as “unilateral aggression on the part of Zionism, when in fact the Palestinian narrative includes a deep-rooted delegitimization of Israel and Zionism… It’s false and unfair to cast Israel as the sole aggressor.”

In this view, both sides are at fault — and so simply equating Israel with white supremacy doesn’t quite add up.

What about Black Lives Matter and “From Gaza to Ferguson”?

The 2014 Israel-Gaza conflict occurred around the same time as the eruption of the protests against police brutality in Ferguson, Missouri after the death of unarmed 18-year-old Michael Brown.

Brown’s death added fuel to the Black Lives Matter movement, which had begun in July 2013 after the acquittal of George Zimmerman in the shooting death of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin.

In one article from 2014, “From Gaza to Ferguson: Exposing the Toolbox of Racist Repression,” two pro-Palestinian activists linked the movement against police brutality with the Palestinian cause. “As in Palestine, resistance in the streets of Ferguson has been met with violence, leading several shocked Ferguson protesters to compare the local police to Israeli occupation forces.”

In 2016, the Movement for Black Lives (which is affiliated with Black Lives Matter) published their 40,000+ word platform, which supported boycotts against Israel, called Israel an apartheid state, and included the incendiary line, “The US justifies and advances the global war on terror via its alliance with Israel and is complicit in the genocide taking place against the Palestinian people.”

For many, calling Israel’s military occupation “genocide” was one step too far.

T’ruah, the rabbinic human rights organization, issued a statement that said, in part, “While we agree that the occupation violates the human rights of Palestinians… the Israeli government is not carrying out a plan intended to wipe out the Palestinians. There is no basis for comparing this situation to the genocides of the 20th century.”

Read more here on Black Lives Matter and BDS.

What about that whole Women’s March and anti-Semitism thing?

Ah yes, that.

Many Jews believe the Women’s March leadership has an anti-Semitism problem, saying they have consistently refused to denounce anti-Semitic remarks and, in doing so, have failed to include Jews in their movement. As Tablet reported, some Jewish women involved in the organization’s early days said they were told that intersectionality meant their experiences as white, empowered women made them suspect as allies.

Back in March of 2018, we chronicled the rising criticisms of the Women’s March, which included the fact that their “Unity Principles” mentioned protecting other marginalized groups but not Jews (after public outcry, they’ve since added Jews to this list), their failure to condemn anti-Semitism after the events of Charlottesville in August 2017 — you know, when Nazis marched the streets chanting “Jews will not replace us” and a white supremacist killed a protester named Heather Heyer — and the leaders’ connections to Louis Farrakhan.

Who?

Louis Farrakhan is the super anti-Semitic and anti-LGBTQ leader of the Nation of Islam.

And what does he have to do with the Women’s March?

Some leaders of the Women’s March seem to be quite cozy with Farrakhan, like Tamika Mallory, who posted a picture of herself with him, calling him the GOAT (“Greatest of All Time”), and Carmen Perez and Linda Sarsour, who have offered similar praise.

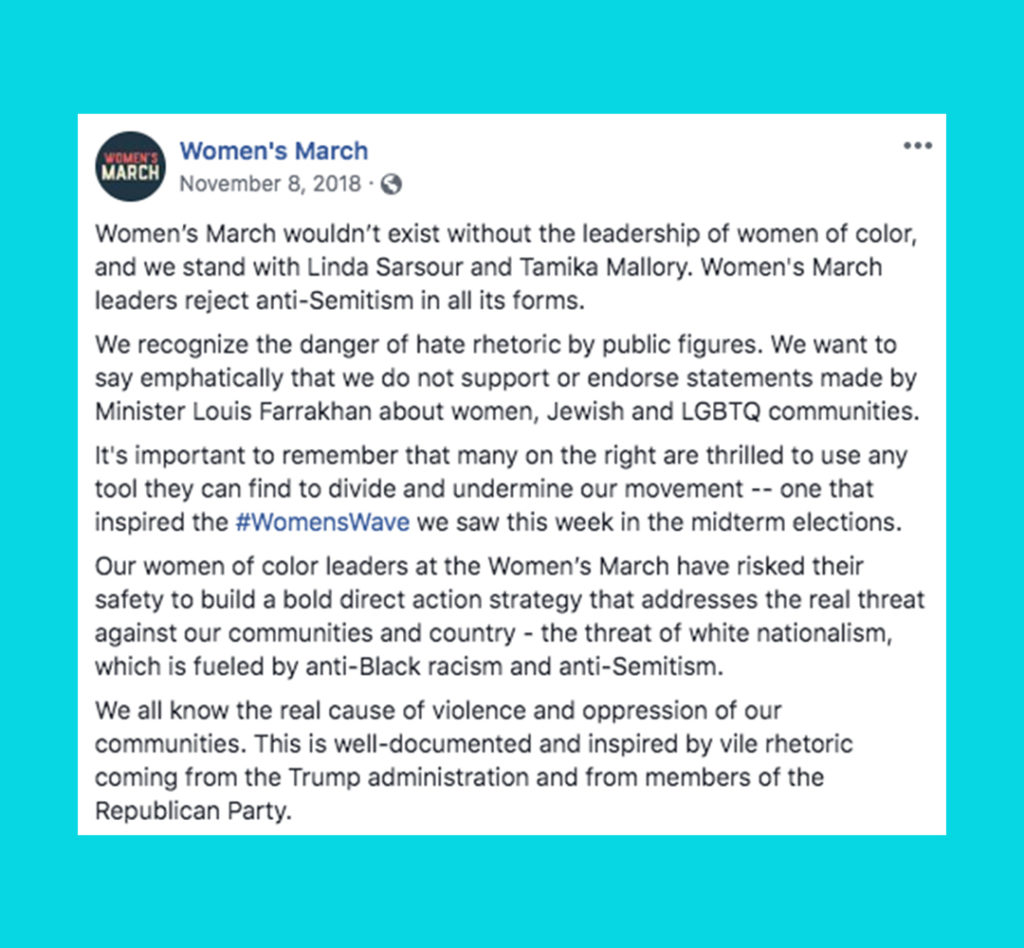

After public outcry, the Women’s March leadership refused to denounce him or break ties, until they (kinda) did, not long after actress Alyssa Milano spoke out:

But many Jews thought that was too little, too late.

It’s a really messy issue — surprise surprise — one that has no easy answers. Hey, kind of like this entire conflict!

2014 Israel-Gaza conflict

Known to Israelis as Operation Protective Edge, this was a military campaign launched by Israel in 2014 in response to the kidnapping and murder of three Jewish teenagers by Hamas.