The Palestinians

Who are the Palestinians?

Part of: Hey Alma’s Guide to the Israeli-Palestinian ConflictThe slogan “a land without a people for a people without a land” was popular among some early Zionists when referring to what would become the State of Israel. However, in the 1920s, when the British were in control of what was then widely known as the “Holy Land” or “Palestine,” the population included 162,000 Jews and 790,000 Muslim and Christian Arabs. The clashing nationalist aspirations of the Jews and the Arabs in the land between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea, which had for the previous 400 years been under the rule of the Ottoman Turks, sits at the heart of this whole conflict.

Here, we’ll break down who the Palestinian people are and what most people mean today when they say “Palestine.” Ready?

Is Palestine mentioned in the Bible?

Sorta. Plištim (Aramaic) appears, mainly in 1 Samuel, referring to the Philistines. The Philistines — if you know your Hebrew Bible (it’s okay if you don’t!) — are a sea-going people in conflict with the Israelites. Today’s Palestinians — falastin in Arabic — took their name from the land named for the ancient people, although few claim to be directly descended from their biblical namesakes.

When did people start referring to the land as Palestine?

The name “Palestine” has appeared on countless maps and documents throughout history, starting all the way back with hieroglyphics on an Ancient Egyptian temple in 1150 BCE.

When Jews ruled under various configurations beginning circa 1000 BCE, the area was variously known as the Kingdom of Israel, Judea and Samaria. Under the Roman Empire, Jewish sovereignty ended in the Holy Land. By 70 CE, “Syria Palæstina” was a province that combined Roman Syria and Roman Judea. So, the name of this region changed from Judea to Palestine, possibly to minimize Jewish connection to the land.

Let’s fast forward a few hundred years…

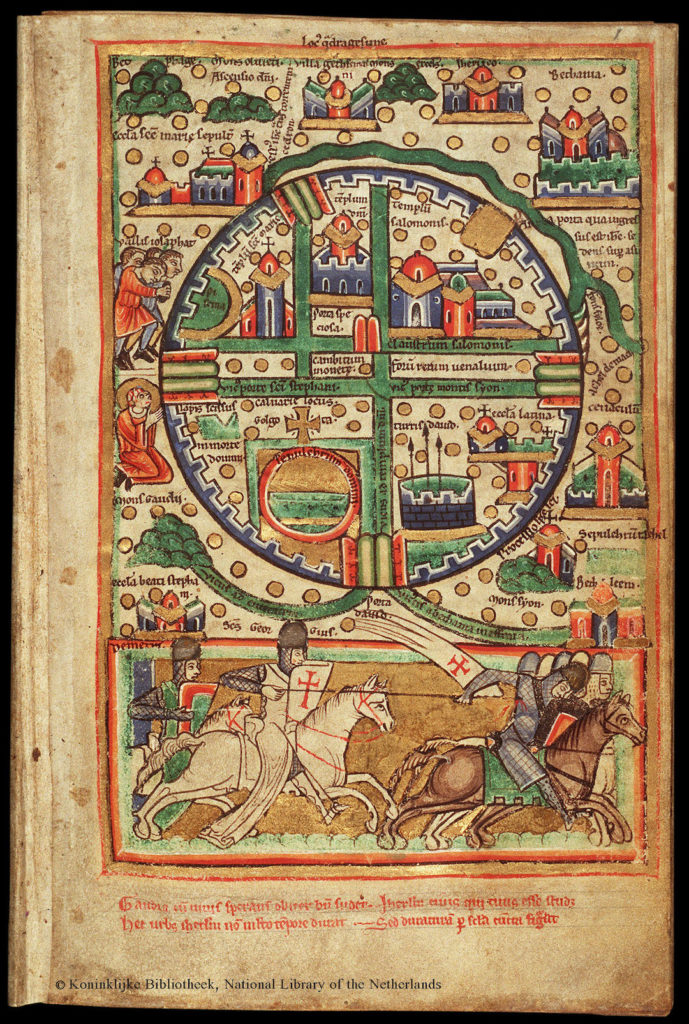

Palestine becomes a province of the Byzantine Christians circa 390 CE, then the Umayyad and Abbasid Muslim Caliphate. Then the Crusades happen (Christian warriors headed to the Holy Land to win it back from the Muslims) and many of their maps and descriptions refer to Jerusalem as situated in the land of Palestine (Judea and Samaria are called a “part” of Palestine).

Fast forward again to… the Ottomans. The far-flung Turkish empire starts around 1300, and, whadya know, Palestine, or the “Mutasarrifate of Jerusalem,” becomes an Ottoman district by 1516 or so, including all the major place names we know today (Hebron, Jaffa, Jerusalem, Gaza, etc.).

When did the Palestinians enter the scene?

So when did Palestinian national consciousness — and Palestinians as we know them today — emerge? Lots of people have lots of different perspectives (like most things in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict!).

Starting in 1516, the area of Palestine was ruled by the Ottomans. Living there were longtime inhabitants, migrants from neighboring Syria, Lebanon, and what is now Jordan, and a small Jewish community. In 1834, there was something called the “Peasants’ Revolt,” which some scholars point to as the formative event of the Palestinian people.

Rashid Khalidi, a prominent Palestinian historian, argues Palestinian nationality/identity has never been exclusive, arguing that Arabism, Islam, and local loyalties all play critical roles. Other historians argue that Palestinian nationalism only emerged as a reaction to Zionism in the Mandatory (British) Palestine period. (Khalidi writes, “Although the Zionist challenge definitely helped to shape the specific form Palestinian national identification took, it is a serious mistake to suggest that Palestinian identity emerged mainly as a response to Zionism.”)

Some right-wing politicians in Israel question whether the Palestinians are “really” a people that need their own state, suggesting they can just live in Lebanon, Syria, or Egypt — or in Jordan, where there already is a majority Arab population with roots in the Holy Land. Obviously, Palestinians — and many others — would beg to differ. Arabs living in the West Bank and Gaza, and those descended from people who left or were expelled from present-day Israel during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, insist their identity is distinct from other Arab nationalities and intimately tied to this specific land.

Regardless of the past (which is a weird thing to write in an article all about the past!), Palestinians today consider themselves a distinct people with their own particular history and culture.

So what does Palestine refer to today?

When people talk about Palestine today, what do they mean? Typically they’re referring to the Palestinian territories — the West Bank and Gaza Strip — captured by Israel in 1967. But some also use “Palestine” to refer to the entire area between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River, including pre-1967 Israel. The Palestinian Authority, or PA, refers to the interim self-government body established in the 1994 Oslo Accords. (Read more about Palestinian politics here.) A majority of the United Nations member countries recognize a “State of Palestine,” although its borders have not been determined.

That’s why, when some people argue for the “liberation of Palestine,” it can be understood to mean either the destruction of the State of Israel, or just the end of the occupation in the West Bank and the creation there (and perhaps also Gaza) of a sovereign Palestinian state.

Many Palestinians hope for a state in all of historic Palestine. The common political slogan used by Palestinian activists, “From the river to the sea, all of Palestine will be free,” telegraphs this desire. Groups like Hamas still refer to Israel as the “Zionist entity” — they do not acknowledge the legitimacy of the State of Israel, or that Jews have any ties to the land.

But in general, it’s safe to say the international community understands Palestine as the land in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, which is where a Palestinian state would most likely be established.

Palestinian Authority

The Palestinian Authority is a Palestinian governing body established for the purposes of Palestinian self-government by the 1994 Oslo Accords.

1948 Arab-Israeli War

The 1948 war was a conflict fought between the newly established State of Israel and a coalition of Arab armies. Israel regards the conflict as its War of Independence while Palestinians refer to it as the Nakba, or “catastrophe.”

Hamas

Hamas is a militant Islamic organization that engages in both acts of terrorism against Israel and serves various social welfare functions. Founded as an offshoot of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood, Hamas became the governing authority in the Gaza Strip in 2007.

Oslo Accords

The Oslo Accords were a series of agreements signed by Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization aimed at achieving a peace treaty between the sides and a final resolution of the conflict.

West Bank

The West Bank is the territory captured from Jordan by Israel in 1967. It remains the core piece of disputed territory between Israelis and Palestinians.

Gaza

The Gaza Strip is a coastal territory bordered by Israel, Egypt and the Mediterranean Sea. The strip was occupied by Israel following the 1967 war and returned to Palestinian control in 2005.