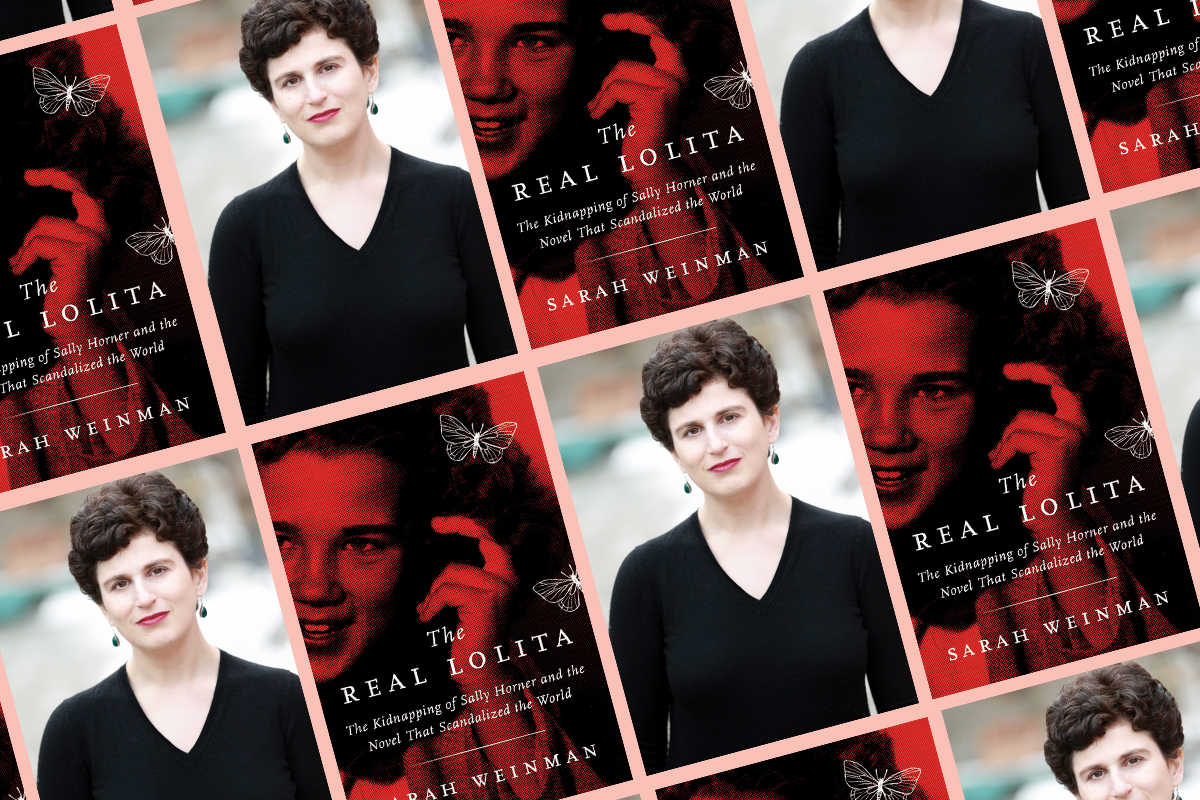

Sarah Weinman’s new book, The Real Lolita: The Kidnapping of Sally Horner and the Novel that Scandalized the World, tells the true story behind Vladimir Nabokov’s famous Lolita.

If you didn’t know Lolita was based on a true story, join the party. Weinman deftly tells the tale of Sally Horner, who has been forgotten to history. The outlines of Horner’s story, abducted at age 11 in 1948, fits the outlines of Lolita.

But Nabokov did not want anyone thinking he based his famous Lolita on a real case. As Weinman writes, “To admit he pilfered from a true story would be, in Nabokov’s mind, to take away from the power of his narrative. To diminish the authority of his own art.”

We had the chance to chat with Wienman about her book and what it’s like being a Jewish female crime writer today.

You write in the introduction how crime stories “ignite within me the twinned sense of obsession and compulsion. If these feelings persist, I know the story is mine to tell.” When did you realize Sally Horner’s story was one you just had to tell?

It was around late 2013, if I had to date it back. I’ve always been interested in stories where crime intersects with culture. Stories where I see a broader input into American society, in particular, really fascinate me. So, I was looking around for my next story, as is my want, and I went on essentially a late night internet rabbit hole — which had served me well in finding previous story ideas.

I had read this Times Literary supplement piece, which had connected Sally Horner’s kidnapping with Lolita in a pretty concrete way. But somehow when I found it again, on this late night, something really stuck with me. And I started asking myself, had anybody actually reported out Sally’s story and what happened to her? Were there people still alive? Could I find documents? Could I find court cases? I started to dig, and it just became this incredible, heartbreaking, tragic story.

It felt like there was this amazing story that had not been fully reckoned with, especially in the context of what Nabokov knew about Sally’s life, kidnapping, rescue, and death, and when he knew it, and what influence it had on Lolita.

Do you think Nabokov thought no one would make the connection to Sally’s story?

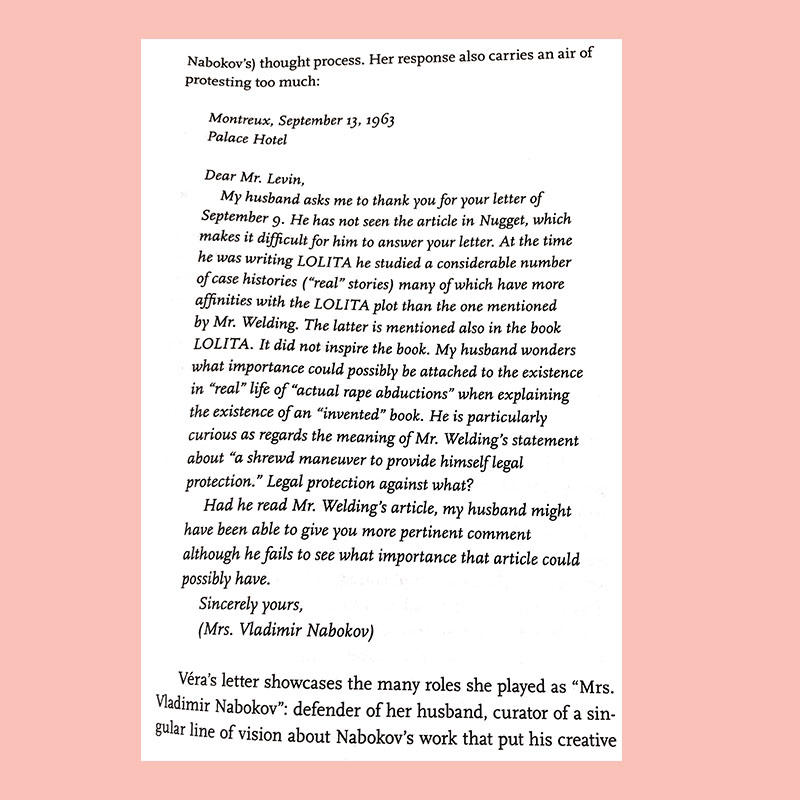

A few years after Lolita published, someone did make the connection. There’s the chapter about Peter Welding, a burgeoning freelance writer [from] Philly, who learned about the case from the Enquirer, and thought this was a very interesting story to pursue. And he pursued it in a way that was a little bit surface, but it did attract the attention of this guy Al Levin, who was a New York Post reporter, who wrote the Nabokovs asking what was up. And they slapped it down pretty definitively. Like, [Nabokov’s wife] Véra —

She wrote that letter!

That letter is a remarkable document.

Amazing.

It’s such a window into how VN — which is, of course, their shared initials — operated and how they really tried to fashion their particular narrative about how Nabokov’s books were made. I think [they thought] if people started paying attention to Sally’s story as influence, it might make Lolita more facile, especially since he was somebody who really decried mapping real life influence to art.

Why do you think it’s so important for us to know Sally’s story?

I think it’s incredibly important for us to know what influence Sally’s story had, and to some degree, other real life stories had, on Lolita. Because no work of art can be separated wholly from influence. Like, art for art’s sake is a really interesting concept; certainly, everything that helped produce Lolita could’ve produced something a lot more mediocre. The genius is still the genius, the language is still the language. Just because [Nabokov] may have need[ed], or alighted, on Sally’s story to help him on structural or plot things in Lolita, it doesn’t take away from its brilliance.

I had read earlier this summer Adrienne Celt’s Invitation to a Bonfire —

Isn’t that a wonderful novel?

Yes, and it got me thinking about the Nabokov marriage, and then I read your book, and I was like — oh my god, I need to know so much more about them! So, Véra really struck me as I was reading. How do you feel about Véra and the role she played as “Mrs. Vladimir Nabokov”?

She remains a little bit elusive to me, and I think that was by design. Understandably, to create my portrait of her, I drew very heavily from Stacey Schiff’s exemplary biography of her. I view that [biography], in a way, as a model because Schiff really needed to kind of plumb the absence to create her portrait — because Véra destroyed almost all of her letters to Nabokov.

Véra would lie to biographers’ faces about certain things. When they would ask her, oh did Nabokov have this mistress, Irina Guadanini, she would flat-out, to their face, say no. And then, [Nabokov biographer] Brian Boyd was like, “Well actually, I have some letters.” So she kind of backed down. I think it was just critically important for her [to be] Mrs. Vladimir Nabokov.

I kind of view her as one of the first literary brand managers, in all of its complexities. She wasn’t just his wife; she was essentially his agent, his manager, his letter writer. There’s one story — apocryphal or not — about her licking his stamps. I mean, she was a true partner.

How much did she sublimate her own creative desires and the like? That’s not for me to say. But I think in the choices she made, she felt like it was much more important to support his ability to make art then it was for her to have some independent identity. But I also get the sense that in making those decisions, she actually felt she could wield a lot more power. And so that was a conscious choice. And certainly, we remember her a lot more than a lot of literary spouses, who may not have made those choices.

What was the most difficult part of writing this book for you?

There were two things, with respect to Sally’s story. Because I was dealing with material — a story that started 70 years ago — it meant that there was a lot of documents that had gone missing, [and] there were people who I wanted to talk to who passed away before I could or they died just after I talked to them.

The thing about being a journalist is once you have a source, you want to feel like you can go back to them time and time again. So, on the lucky side, I feel very grateful I was able to find Sally’s best friend Carol before she passed away, and I got to talk to her. I had two telephone conversations with her that were absolutely invaluable because they really gave me some insight into what Sally was like after she came home.

And in terms of the Nabokov [part]? It’s like I say in the introduction, I’m essentially walking in his shadow. He’s a daunting figure. For me to kind of try to intuit what he was thinking and what he knew — that’s a really scary, and also thrilling prospect. So at first I was a little tentative, and it took a while in rewrites to get the confidence to be like, here’s what was going on. And here’s what I think. And here are the connections I can make.

So it was just a matter of overcoming an initial reticence and assert an authorial confidence that frankly Nabokov, if he didn’t have it, he certainly pretended like he did his whole career.

What’s your favorite crime story? Or one that has stuck with you?

[Laughs] That’s a tough one!

I’ll answer it this way: I have a mental checklist of cases that haunt me. Part of that is just going back to being a kid in Canada, growing up, and getting obsessed with crime as a way of trying to understand the world and wanting to know why bad people do bad things to other people.

A story I think about a lot, especially because I don’t think it has a satisfactory conclusion, is the disappearance of Etan Patz. I remember hearing about it when I was young; he disappeared in ’79, which is the year I was born. He disappeared [when] he was 6 years old, and he went out to the bus stop — it was the first time he walked from his house to the stop by himself — and he was never seen again. It’s a story that really cast a pall over NYC, and it really kind of predated the kind of “stranger danger” idea that has become incredibly prevalent in American, and also Canadian, society.

The reason I say it was unsatisfactory is that there was a prime suspect for a long time, there was a civil suit where he was obliged to pay Etan’s parents, but of course, another suspect was discovered and is now, I believe, serving time in prison after a second trial. And I still feel like there are unanswered questions. It just doesn’t fully sit right. So I don’t know if that will ever be fully resolved. But mostly, I think about this poor little boy who just wanted to go to school.

As a female true crime writer, do you ever feel like true crime is a male-dominated genre?

What I’m finding interesting is how many women are getting into the field, and I sort of have a habit of trying to keep track of who are my colleagues in this dark endeavor.

There have been a spade of really great true crime memoirs by people like Leah Carroll and Sarah Perry and Carolyn Murnick. And obviously, Michelle MacNamara’s I’ll Be Gone in the Dark was understandably a spectacular but very bittersweet success. I was definitely an admirer of her work, I thought she was a beautiful writer. When I heard she was working on this book based off [her] LA Mag piece on the Golden State Killer, I [thought] if this works out the way it should, it’s going to be one of the best true crime books ever written. And what was published was truly a classic, but if she had lived, it would’ve just been such an incredible, polished, beautifully written book.

And I think of other younger writers who either have books under contract or are about to have books under contract. So people like Rachel Monroe and Emma Eisenberg and Sarah Marshall and Alice Bolin, whose essay collection Dead Girls is phenomenal. And although she doesn’t have a book out yet, Pamela Koloff is one of the greatest journalists there is right now – and she is an outstanding human being and great model for the kind of work that I do. Or like, Michelle Dean’s BuzzFeed piece and her true crime pieces. So I feel like there are a lot of really interesting and great women in this space.

Of course, what I’d like to see are, generally, more people of color. If anything, I think true crime is less about a gender issue; it’s a very white field. And you see that in terms of what kind of stories get highlighted. There’s a common trope, if it’s a missing beautiful white blonde girl — that case will get an incredible amount of media coverage. But if it’s an African American or Latinx person, not necessarily fitting that mold per say, their stories might get unnecessarily overlooked. And so, I feel like, I know the stories I’m best equipped to tell. But I want many, many more stories from different communities and those are the ones that I want to make a point of seeking out.

When you’re not reading crime stories, what’s your favorite thing to read?

I mean, just so we’re clear, I’m almost always reading crime stories. And of course, when I say crime stories, it’s not just true crime — I mean, crime fiction was my first and still best love. But, I read a lot of literary fiction. I read a lot, I try to read widely. I just feel like if I don’t read, then I’m not learning. I’ve been a bookish person my whole life, I will always be a bookish person. So, I just want to read stuff that I’m curious about. And it does happen that the vast majority of stuff that I’m curious about is crime stories.

I saw you tweeted that your voice is “super-obscure true crime, make it more Jewish, and throw in some terrible sex”— I love this as a description of your voice, it made me genuinely laugh out loud. Can you expand on this? How did you find your voice?

20something me: wow, what if I take this super-obscure true crime case, change a bunch of details, make it more Jewish, and throw in some terrible sex, maybe I'll be able to publish this story!!

current me: actually…that still works, congrats you had your voice all along

— Sarah Weinman (@sarahw) August 12, 2018

I mean, how does anyone find their voice? You just write, and I think all writers have to write from a place of compulsion. So even though you don’t necessarily think you’re going to repeat yourself, certain themes just keep cropping up over and over and over again. I’m a woman, I like to write about women. Especially if I’m writing in the first person, there’s a certain — a slightly sardonic, but also just a complicated person. Cause I’m a complicated sardonic person.

In terms of writing Jewish, I originally grew up Modern Orthodox, and I am not practicing that way, but it is a standard from which I deviate from. Judaism is very important to me; it’s a world I know, it’s a world I understand, it’s in my bones. I feel like there wasn’t enough crime short stories that reflected that particular world – and so it wasn’t something I consciously chose, but it was something that whenever I write it, it just felt more authentic. It just felt more me. And that’s why I would keep going back, and, as I said, write more Jewish.