Warning: Minor spoilers ahead for Promising Young Woman.

Promising Young Woman is here to take on the nice guys. The film, which premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in January 2020 and was released on demand in January 2021, tells the story of Cassie (Carey Mulligan), a 30-year-old woman who lives with her parents and likes to spend her free time in clubs attracting potential date-rapists, only to teach them a very memorable lesson. As the story unfolds, we learn that Cassie has been doing this because of what happened to her best friend Nina while in med school, who was publicly raped, and, unable to get the school to take action, eventually died by suicide. It’s a rape-revenge story, yes, but it’s so much more than that: Promising Young Woman is a reminder of the dangers of the ever ubiquitous “nice guys” who refuse to accept when they’re not acting, well, nice.

There’s much to discuss about Emerald Fennell’s dark revenge tale — that ending! The music! Director/screenwriter/actress Emerald Fennell herself! — but I found myself fascinated with the casting of those “nice guys,” and how those choices add to the ultimate message of the film.

In an interview with Vulture, Fennell explains, “There’s a huge amount of pleasure in seeing people you’ve loved for a long time doing something that you’re not expecting, and so there is that. But also the stuff, the very specific thing, I think, that Promising Young Woman is talking about is people who don’t know they’re bad. It’s about the guys you are friends with, the guys who are cute and you might go home with. It’s about apartments that we have all ended up in, by hook or by crook.”

She continues, “Promising Young Woman, for me, was always about allegiances and who you trust and to whom you’re willing to give the benefit of the doubt.”

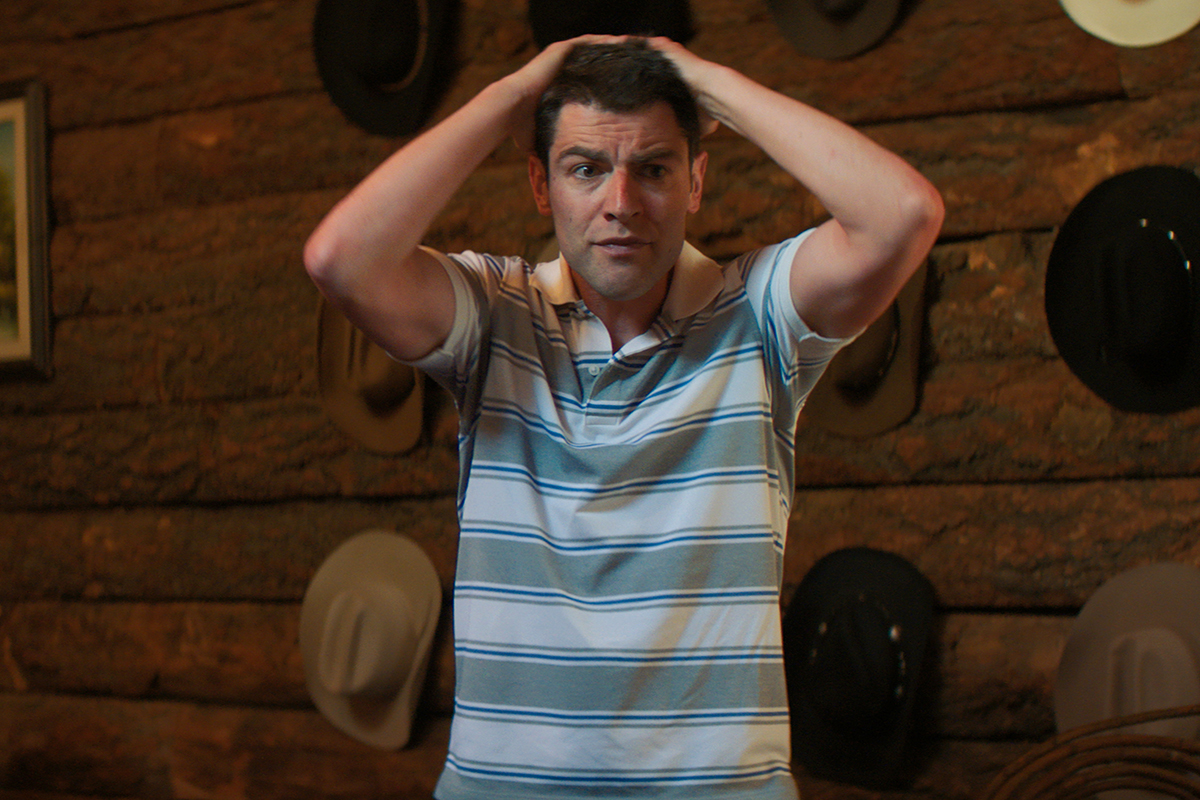

There is no clearer example of this thesis than in the very intentional casting of real-life Hollywood “nice guys,” like Adam Brody and Max Greenfield, as two of the men who take advantage of, and harm, Cassie. Brody is best known for playing dorky heartthrob Seth Cohen on The O.C., and Greenfield stole our hearts as Schmidt on New Girl. Both of them were in roles that could be defined as the Nice Jewish Boy (er, for Seth, perhaps the “Nice Interfaith Boy,” as he famously celebrates Chrismukkah). In Promising Young Women, their characters bookend the film: Brody’s Jerry takes Cassie home when she appears to be black-out drunk, and Greenfield’s frat-boy-man Joe helps another “nice guy” — Nina’s rapist — cover up a horrific crime while telling him “it’s not your fault” and that everything will be okay. Reader: It was his fault, and everything most certainly will not be okay.

As Carrie Wittmer writes in The Ringer, “These lovable, approachable, low-key internet boyfriends are famous enough that we’re familiar with them but not so famous that they can’t go to Trader Joe’s in peace; they’re not Brad Pitt or Timothée Chalamet. And in Promising Young Woman, they’ve been cast intentionally by casting directors Lindsay Graham and Mary Vernieu, and writer/director Emerald Fennell … What all these actors have in common is their wholesome roots. Their previous roles make you feel at ease with their presence, even though in Promising Young Woman, you know that they’re bad or that they’re about to do something bad. Their performances in the film, which emulate their previous roles but with a sinister twist, perfectly capture the film’s message that anyone could be a predator, and anyone could be complicit.”

That anyone could be complicit in rape culture is undeniably the main theme of Promising Young Woman — and that doesn’t just go for men. Madison (Alison Brie), a former med school friend who blamed Nina’s rape on Nina herself for getting drunk, is another victim of Cassie’s plot for revenge, as well as the dean of the school played by Connie Britton.

Yet, watching the film as a Jewish woman, I was struck by the “Nice Jewish Boy” of it all — especially with regard to Brody’s Jerry and Greenfield’s Joe. The term has become ubiquitous in describing pretty much anyone who identifies as Jewish and male, implying that there is an inherent safety with Jewish men that leaves them incapable of doing wrong. But time and again, we can see that’s just not true. In an essay published on Alma in May 2019, Nylah Burton spoke of the dangers of calling a Jewish man a “Nice Jewish Boy,” writing of her own experiences with NJBs who were anything but nice.

“The idea of the ‘Nice Jewish Boy’ endangers Jewish women by anchoring a communal narrative in which only ‘other’ men harass and harm women. It turns communal discussions away from critical appraisal of behaviors within the community by assuming that threats and hazards lurk outside communal boundaries rather than menace women inside Jewish spaces,” Professor Ronit Stahl explained to Nylah. She continues, “The ‘Nice Jewish Boy’ trope exonerates Jewish men before women have even uttered a word and stops hard conversations about consent, harassment, and assault before they begin.”

Indeed, the idea that rapists are strangers has been proven false time and time again; according to RAINN (Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network), eight out of 10 rapes are committed by someone known to the victim. Though that means 20% of rapes are committed by strangers, it is much more likely a person will be a victim of assault by someone they know.

When it comes down to it, anybody can call himself a “nice guy,” but actions will always speak much louder than words. And that’s the power of the casting in Promising Young Woman: We know these actors. We’ve liked these men. They’ve played the crushes, the good guys, the protagonists on our screens. They are the Nice Jewish Boys we joke about on Instagram. But, as the film shows us, that doesn’t mean people like them are by default incapable of harm, whether that harm is physical violence or simply remaining silent while watching others do wrong. The only way to be a nice guy is to be an actual, decent human being, one who doesn’t take advantage of others, one who doesn’t sweep inconvenient truths under the rug, one who always — always — speaks out on behalf of those more vulnerable and owns up to their own shortcomings whenever they can.

“Nice guy” is not a moniker you can simply add to your dating bio. It’s a way of life, a moral code, and nobody is just born that way.