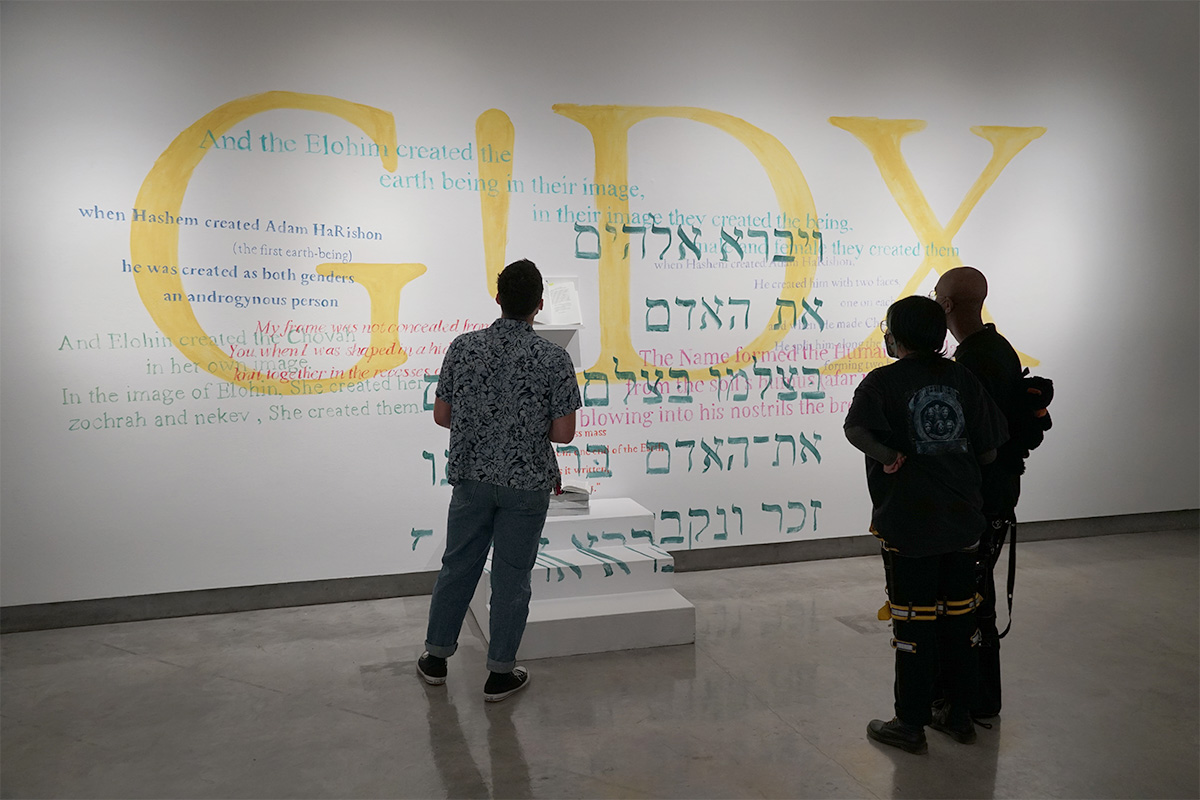

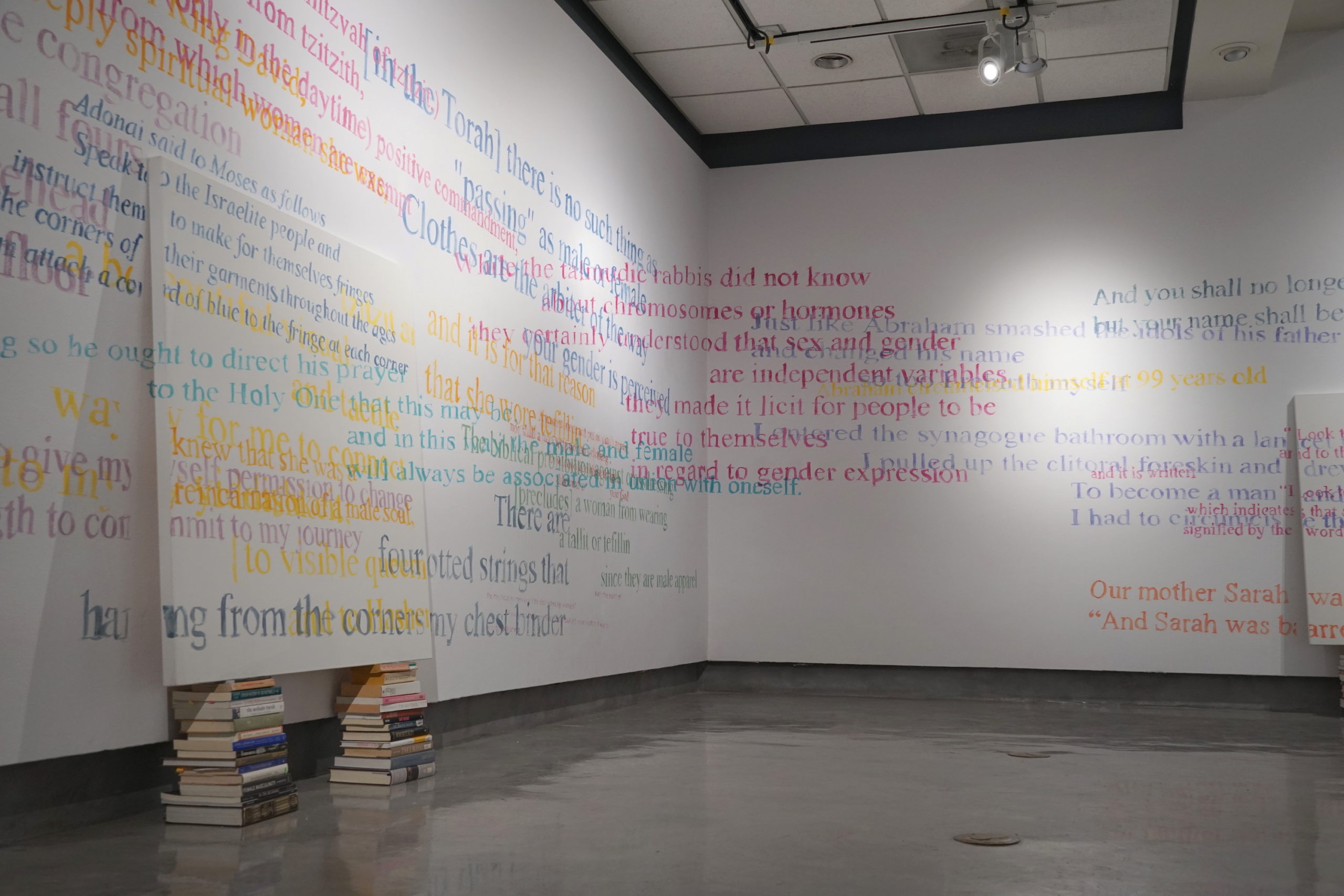

The work of Las Vegas-based artist Laurence Myers Reese always seems to catch me by surprise — in part because he works across so many mediums. One moment, clicking through his portfolio, I’m admiring an artificial intelligence-inspired oil painting; the next, I’m exploring an installation that fills a room, pastel Hebrew and English lettering jumping out from the walls. His work is sometimes ceramic, sometimes textile, sometimes the documentation of an audition for “RuPaul’s Drag Race.” Some of his creations could be tchotchkes perfect for a punk rock, sex-positive bubbe’s china cabinet.

All of it is unapologetically Jewish.

Laurence’s work spans kabbalistic thought, gender euphoria, queer liberation and Talmudic reimaginings, all with eye-catching flair.

I spoke with Laurence about growing up on the outskirts of Judaism, finding an artistic Jewish community, and the outdated notion of the “bad Jew.”

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Can you introduce yourself to me as an artist? Give me an elevator pitch.

So as an artist, I’m interdisciplinary and my background is primarily in painting, printmaking and performance. My current work is mostly painterly and installation-based, using text and geometric images to create an environment that evokes mystical Judaism and questioning gender identity. So I draw a lot on Jewish texts, on queer abstraction and queer formalisms.

How long have you been an artist?

That’s kind of a hard thing to gauge, but, well, I graduated with my BFA in 2012, so I’ve been a professional artist for about a decade now. In my soul? My soul forever. I’m one of those people who’s spiritually of the mind where, you know, Judaism says we’re created in the image of a creator. So therefore, like if we are created in the image of someone who’s creating, we are all creators. So I think of “artist” as a natural state.

You think everyone’s an artist?

Definitely.

Me too. Can you tell me about the Jewishness of your work?

I’ll just say, as an introduction, that I did a thesis for my Master of Fine Arts that focused heavily on the Talmud and gender identity in Jewish text.

My thesis itself and the work around that has been very, very explicitly Jewish and draws on Jewish object making, Jewish illuminated manuscripts and those kinds of things. But before that and after that, I’ve always taken a kabbalistic thought process, a mystical thought process in terms of how I make things.

Text always informs my work. I’m a big reader. I’m a writer. And so sometimes the texts that I’m using or drawing on aren’t necessarily in the work; there are video works that I’ve done that, while the visual content doesn’t necessarily look Jewish, [have] an undercurrent of Jewish sounds that I’ve mixed in. I’ll be drawing from things like Shalom songs and cutting them up and slowing them down. Sometimes, the titles of my works will be referential to Jewish stuff, and it’s funny because I always think they’re Easter eggs and no one will notice them, but I’ll share them with different audiences and people will hear different things.

What is your Jewish background?

So I’m a convert, which is a complicated thing for some people to get, but easier for others to understand. I grew up in a multifaith household with multiple practices and grew up with Judaism as part of that, and formally converted in 2020 during the pandemic. It was a tricky way to live, being outside of Judaism but doing Jewish things, but I think it’s also hard as a convert to feel like I have the authority to speak on things — you know, to be an authority on Judaism in my work.

I’m from Tulsa, Oklahoma, which actually has a huge Jewish population, surprisingly. I think not a lot of people expect that. I grew up going to seders, going to temple. There’s a reform temple there, Temple Israel. We’d have Hanukkah at friends’ houses. I had lots of Jewish friends. I have Jewish family, so just kind of doing Jewish things and having close ties to Jewish friends was a lot of my growth.

That’s interesting. I’m not a convert, and it sounds like you grew up more Jewish than I did.

What’s funny is, I was in Israel on Birthright this year, and it was a LGBTQ+ trip.

So there’s 30, maybe 25 LGBTQ+ Jews, ages 26 to 32, there — I think I’m the only convert in the group proper. And of everyone, along with this other person who grew up ultra-Orthodox, oftentimes we were the two people telling the others, “oh, yeah, this is Shabbat and this is Havdalah” — you know, things that I now take for granted knowing, because I had to learn them.

There are a lot of people who don’t grow up with that and sort of take Judaism or being Jewish for granted and are reconnecting through that. A lot of my friends on the trip said I’d taught them a lot about Judaism — well, yeah, because I had to learn and read so much as part of the conversion process.

I feel like the intrinsic Jewish experience is imposter syndrome, feeling like you’re always playing catch up. Did your Birthright experience make you more confident in being in Jewish spaces?

Yes, definitely. Even before that, I think having had a roommate who also went on Birthright to connect to his Jewish experiences helped. He grew up multi-faith and came back from Birthright right before we moved in together. We put up a mezuzah in the house. We started celebrating Shabbat together, and he reconnected to his Judaism while I was learning about it. That relationship helped me realize, “Oh, right. Everybody’s kind of learning.”

I don’t know if you listen to “Judaism Unbound,” the podcast, but their most recent episode was on being a “bad Jew,” and this idea that so many people carry — you’re right, this imposter syndrome of “I’m a bad Jew, I don’t do this or that, I don’t eat kosher,” and so on. It’s like, sure, by that standard, there are millions of bad Jews out there.

Are you a bad Jew?

Hmm. I guess I’m no more a bad Jew than I am a bad person. I’m a person who does good things and a person who does bad things, but I try to stay away from that term. I think I try to ignore it, because I think that comes along with the same imposter syndrome of conversion or, more importantly, gender. There are definitely going to be people out there who invalidate my conversion, and then, more so, invalidate my gender identity because they see those as incompatible. Not that there’s a ton of people out there who would necessarily do that, but I’m not gonna feed them, you know? I’m not going to give them the rope to capture me with.

If all of your art is informed by a Jewish process, does that make all of your art Jewish?

In a sense, in the way that all of my art is trans, or all of my art is Mexican-American, I guess. You know, what is Jewish art? What does Jewish art look like? That’s what I’m thinking.

Have you always made Jewish art, then? If you’ve been an artist forever?

That’s a good question, because I do think there’s a time I can go back to and start noticing the Jewish elements in my art. I couldn’t say a date, but there’s a time period in which I was painting a bunch of still lifes and, all of a sudden, my still lifes started to involve candlesticks, two candlesticks, bread, wine, pomegranates. I believe there’s one with beetroot. There are certainly elements informed by me going to seders and Shabbat and, you know, this was pre- my converting to Judaism, but post-me wanting to identify as Jewish. I think it’s the same with being trans. I think there was a long time in which I went, “I think I’m Jewish, but I don’t know how to go about that,” and there was also a long period of time in which I was like, “I think I’m trans, but I have no idea what to do about that.”

It’s funny, but I think it’s a lot easier to say I know I’m trans than to say I know I’m Jewish. How can you know you’re Jewish, right? So there was a long time leading up to it with me thinking, can I convert? Do I have the right to convert? Am I Jewish enough to convert? It feels hilarious to think about now.

Who are some Jewish artists that inspire you?

One artist I really love right now is Yael Kanarek. She’s really known for her Torah work where she’s retranslated the entire Torah, flipping all the genders. Before that, she had been doing a bunch of text-based work where she was carving into walls, writing words over and over on top of each other, very Jewish text-based exploration. She’s Israeli originally, so I think that informs a lot of her identity-based work. She investigates a lot about womanhood and Judaism, and she’s an excellent designer. I just love her treatment of text, too.

I’m also really interested in zine making. The Jewish Zine Archive is one of my favorites. Chava Shapiro, who is not far from me, actually, in Tucson, is a prolific zine artist.

Then there are artists like Cassils and Kris Grey, though I don’t know if Kris is Jewish. Their work doesn’t look visually like mine, but their treatment of the body is something that I find really interesting, and the way they look at the interactions of the body with history. I can say they’re both incredibly intelligent, and they take their work extremely seriously. Aspects of their work really inform mine.

There’s a writer who just came out with a book called “Trans Talmud,” Max K. Strassfeld, and he was always one of my influences. His book came out like two months after my thesis, which was so awesome. It felt like perfect, perfect timing.

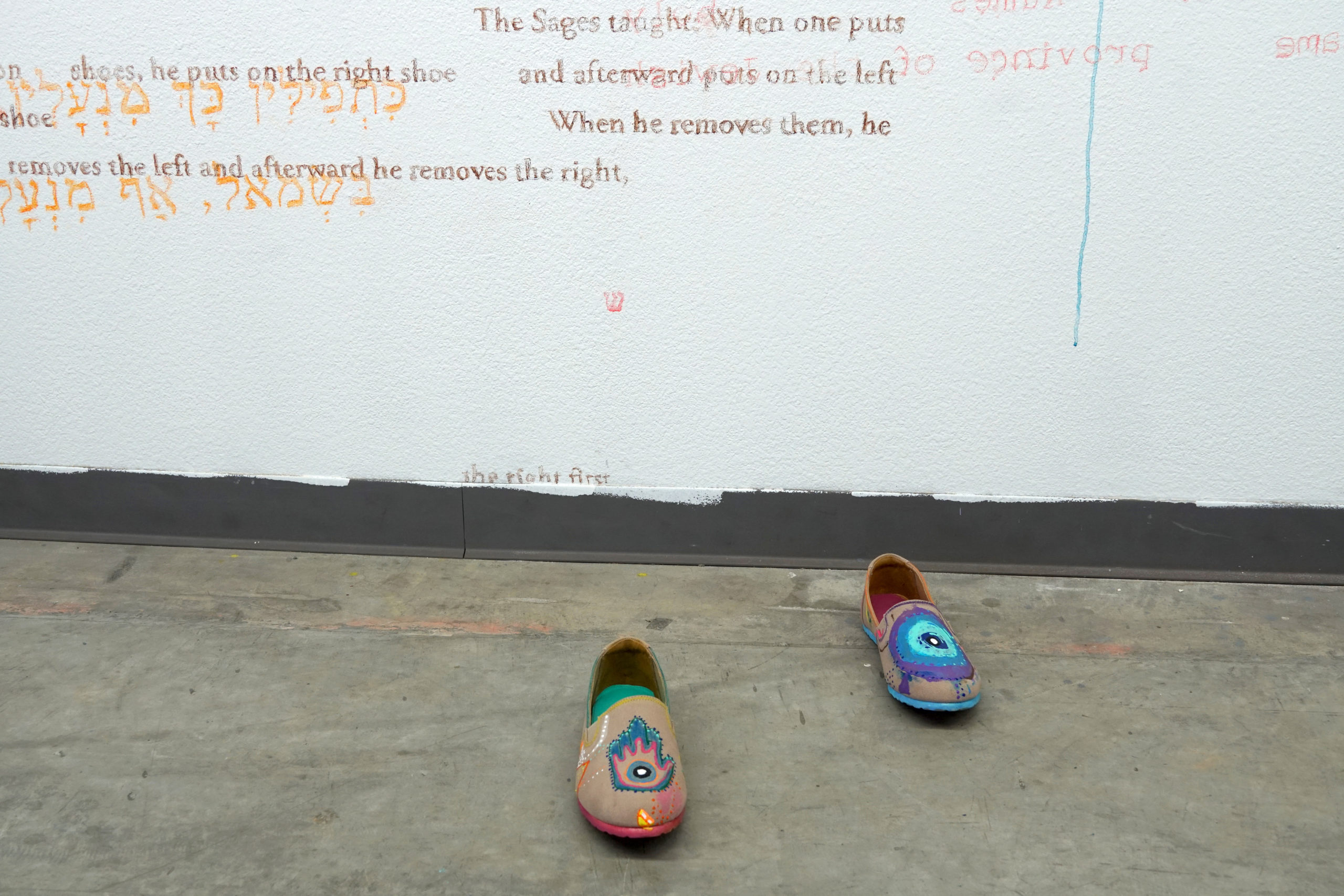

Watercolor fresco, mixed-media shoes, 2021. Courtesy of artist.

Do you have any advice for an aspiring Jewish artist, or someone who might relate to your practice? Advice to your younger self?

If I could give advice to myself or anybody, it would be this: Don’t be afraid of asking or reaching out to people. I was so surprised when I started this thesis project — I just started reaching out to people I didn’t know, and it was scary, but a totally rewarding experience. It never hurts to talk to people. Just take risks and don’t be afraid to say what you mean.

Be honest with yourself. And that doesn’t always mean telling your deepest, darkest stories, but just being honest in your work in a way that’s not pretending to be something else. Unless, say, it’s performance art that’s pretending to be something else, but there’s an honesty in that too.

Either be honest or fake, you know? Just be honest about what you want and about how you want to present yourself.