“When I first started interviewing her, if I asked her questions that she didn’t want to answer, she would just pretend not to hear them,” Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s biographer Jane Sherron De Hart explains to me. “She would just ignore them.” As Ginsburg got more comfortable with De Hart, she opened up more. And over nine interviews and nearly 15 years, she trusted De Hart to tell her story, from her childhood in Flatbush, Brooklyn, through her legacy on the Supreme Court.

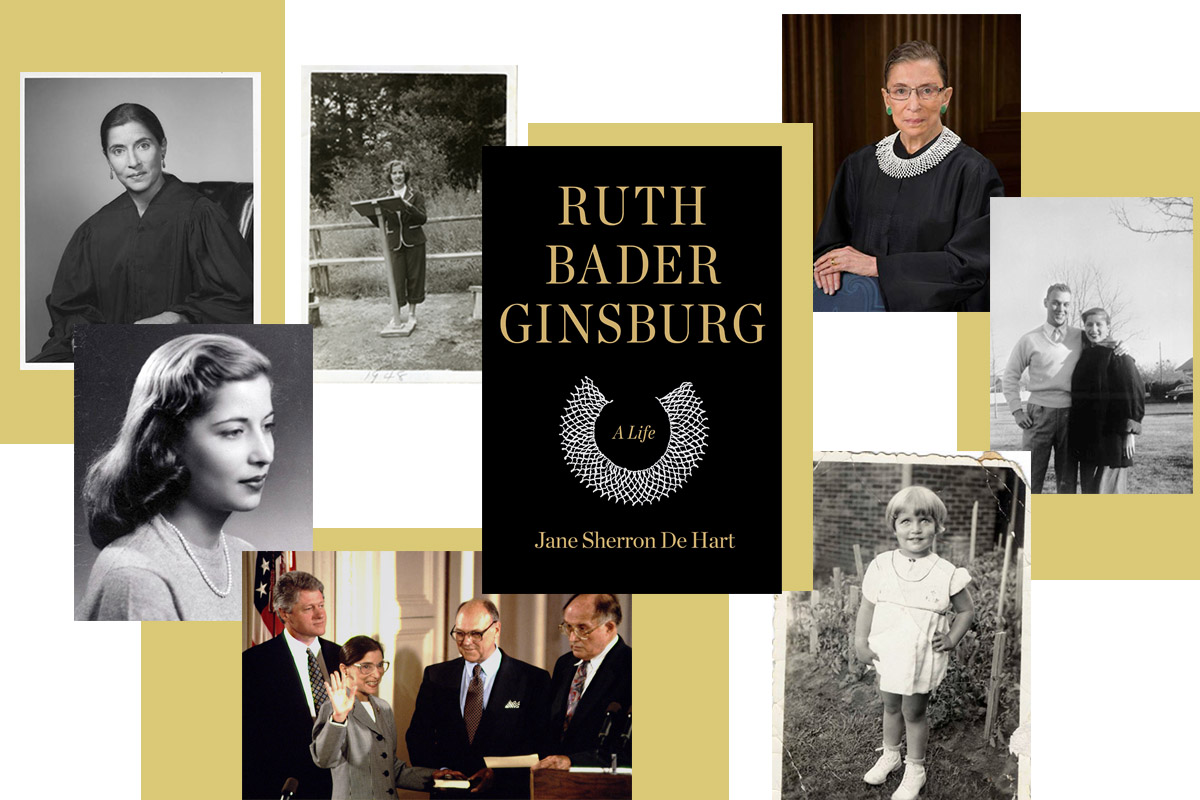

Ruth Bader Ginsburg: A Life by Jane Sherron De Hart is the first comprehensive biography of Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Released this week, the book is a remarkable 500-page look at the famed justice’s life and achievements. The biography sets out to understand the “private, public, legal, [and] philosophical” life of Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

When I started reading the biography, I wanted to know everything about her. What was she like as a child? How did she fall in love with her husband? What inspired her iconic dissents? How did she become so iconic? And, most importantly, why is she so beloved by liberal millennials — particularly Jewish millennials? What made her the Notorious RBG she is today?

De Hart tells me that in recent years, Ginsburg has become such an iconic figure because there’s “the sense that she is speaking truth to power.” She’s become larger-than-life (even though she is physically so, so tiny).

With the rise of RBG’s celebrity status — the documentary on her life, the forthcoming biopic (with a song by Kesha!), the countless tweets and odes to her — where does the biography fit in? It seeks to understand her impact on laws and courts, which is so important, but it also seeks to understand Ruth herself. Most notably, her family and her relationship to her Jewishness.

The questions of Ginsburg’s Jewishness is one that comes up again and again. In her iconic quote about trying to get a job after graduating from law school in 1959, she says, “I had three strikes against me. First, I was Jewish, and the Wall Street firms were just beginning to accept Jews. Then I was a woman. But the killer was my daughter Jane, who was 4 by then.”

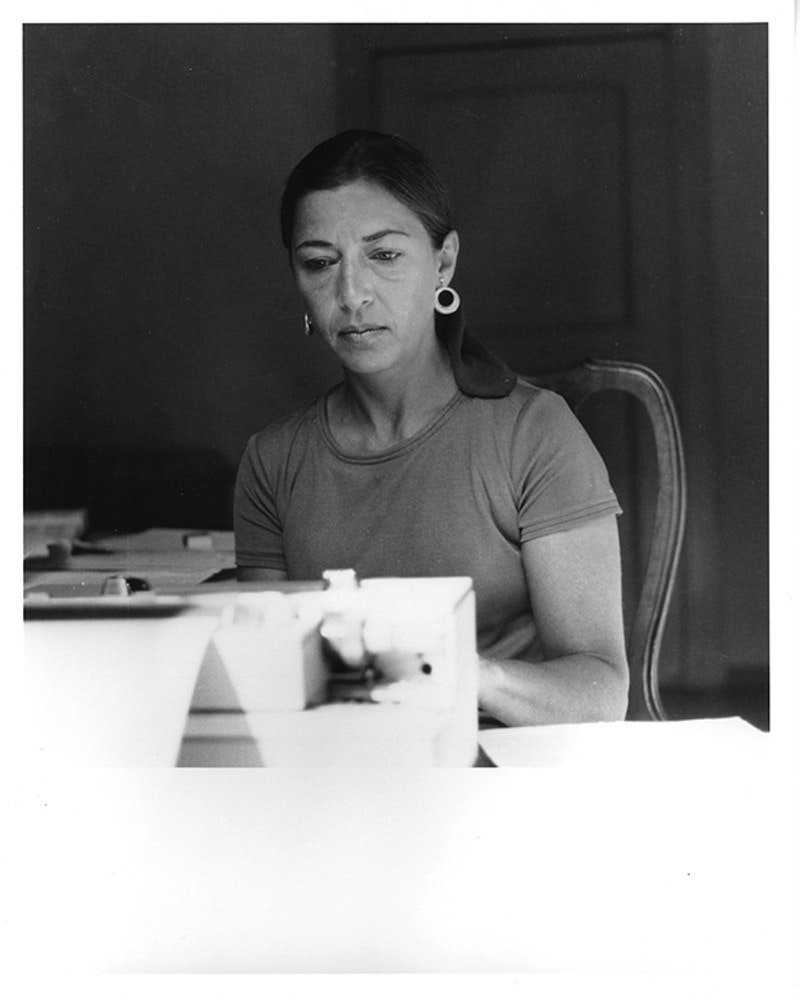

When De Hart started interviewing Ginsburg, she was a “very serious person.” De Hart would arrive in her chambers and “she would never so much as say hello until she finished working at her desk.” She wasn’t very eager to talk about her childhood in Flatbush, Brooklyn because of the “sadness identified with” that time (Ginsburg’s elder sister, Marilyn, died of meningitis when Ginsburg was only 2 years old).

Yet, however reticent Ginsburg was to speak about her childhood, the biography still gives you a full portrait of her as a child. De Hart makes clear the impact Ginsburg’s mother, Celia, had on her. She writes in the biography how Celia “introduced her daughter to women who demonstrated what it meant to be Jewish, American, and female. These were women of valor, Celia explained, by virtue of their courage and humanity.” These women of valor included Jewish feminist trailblazers like Emma Lazarus, Henrietta Szold, and Lillian Wald.

Celia would pass away from cancer two days before Ginsburg graduated from high school. De Hart emphasizes the impact of how Celia taught Ruth the Jewish value of tikkun olam, healing the world.

“I think that [tikkun olam] was very much emphasized by her mother,” she explains, “and I think it made particular sense for a child growing up in the depression, in World War II, learning about the Holocaust, and the huge need for repair after the atrocities of the war and the Holocaust. I think [Celia] emphasized the sense of social justice that is very often a part of Judaism.”

In an essay from June 2, 1946, a young Ginsburg wrote in her synagogue bulletin about the Holocaust. While not included in de Hart’s biography, but in My Own Words (RBG’s collection of speeches and writings), I found it really telling of this impact Celia had on teaching Ginsburg about her heritage. “The war has left a bloody trail and many deep wounds not too easily healed,” Ginsburg writes. “Many people have been left with scars that take a long time to pass away. We must never forget the horrors which our brethren were subjected to in Bergen-Belsen and other Nazi concentration camps. Then, too, we must try hard to understand that for righteous people hate and prejudice are neither good occupations nor fit companions.”

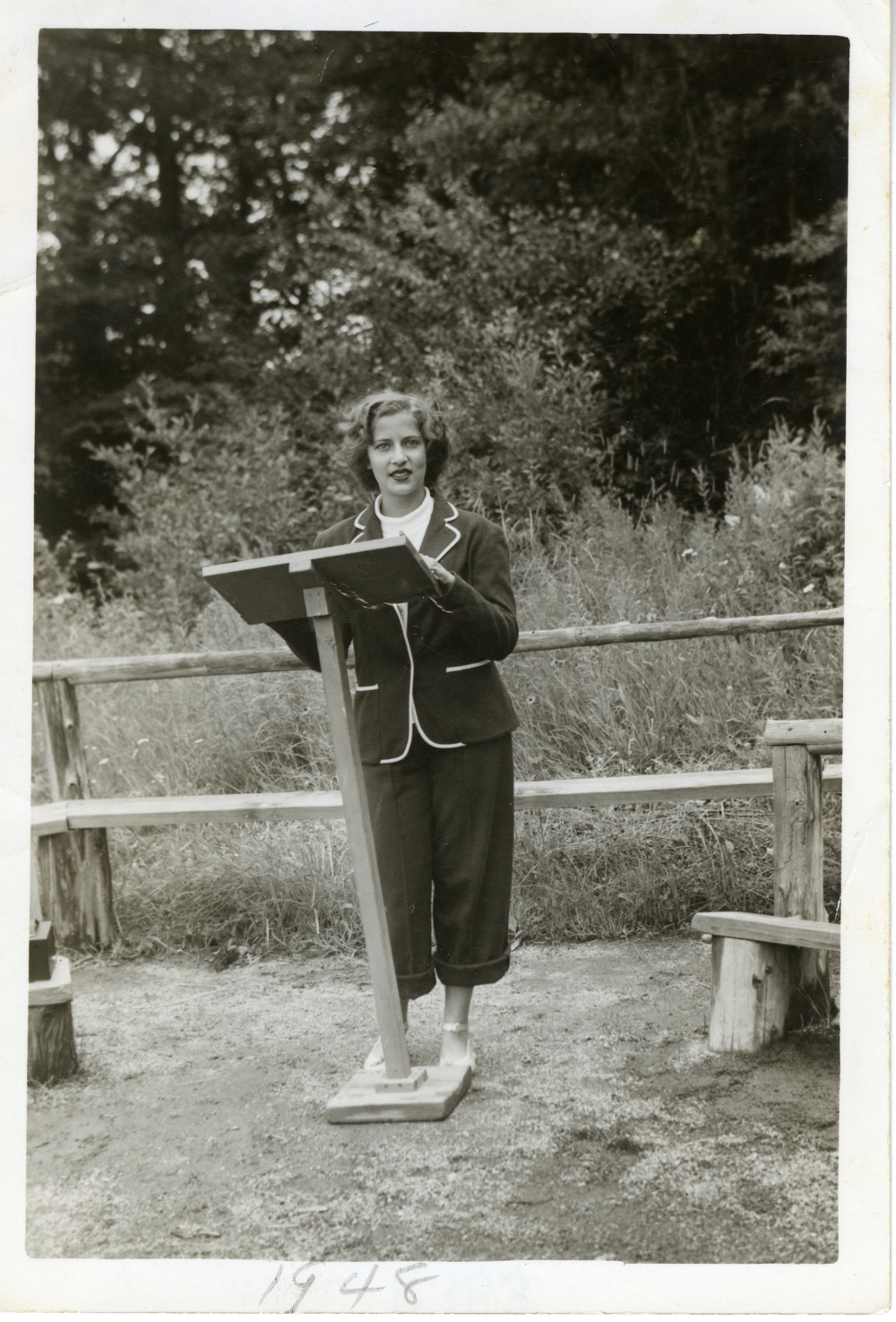

Clearly, as a 13-year-old, Ginsburg was involved in her Jewish community. When she attended summer camp at Camp Che-Ne-Wah in the Adirondacks (owned by her uncle, Sol Amster, and his wife Cornelia), she acted as “Camp Rabbi.”

However, Ginsburg hasn’t been identified with a synagogue or a temple since her mother died. One thing that pushed her away from organized Judaism was, as De Hart points out, “the fact that women could not take place in the minyan.” De Hart also points to another pivotal moment in Ginsburg’s young adulthood that alienated her from establishment Judaism: “Her father’s business went bankrupt, and he was obviously terribly depressed by her mother’s death, and he had sort of an emotional collapse, and was really living for a while on the money that Ruth had given him — the money that her mother had saved for Ruth’s college.”

“During that time,” De Hart continues, “attending service on the High Holidays required membership and he couldn’t pay his dues. [So] the combination [of] a mother who had so emphasized what women had accomplished — couldn’t take part in saying the Mourner’s Kaddish during shiva — and the fact his father lost his seat the temple really created a break between any sort of formal attendance at synagogue and at membership and at temple.”

Many years later, when Ginsburg’s granddaughter, Clara, was living in Washington D.C. with her grandmother before she attended Law School, Clara — raised in a multifaith family — wanted to attend the High Holidays services. De Hart remembers, “Ruth was so interesting about it. Because she said, [she was] really impressed, it was a female cantor, and there was a female rabbi, and then she sort of got quiet and she said, you know, if that had been true, earlier, things might have been different. I thought she was referring to her own way of observance.”

Yet, Ginsburg keeps her Jewish heritage at the forefront of her work, as De Hart points out again and again in the biography.

Ginsburg herself summed up the impact her Jewishness has had on her at a speech she gave at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in 2004, saying, “My heritage as a Jew and my occupation as a judge fit together symmetrically. The demand for justice runs through the entirety of Jewish history and Jewish tradition. I take pride in and draw strength from my heritage, as signs in my chambers attest: a large silver mezuzah on my door post, gift from the Shulamith School for Girls in Brooklyn; on three walls, in artists’ renditions of Hebrew letters, the command from Deuteronomy: ‘tzedek, tzedek, tirdof’ — ‘Justice, justice shall you pursue.’ Those words are ever-present reminders of what judges must do that they ‘may thrive.'”

De Hart ends her biography when Ginsburg was in Israel in July 2018, just a few days before President Trump nominated Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court.

De Hart writes that at a screening of RBG (the documentary) in Jerusalem, “Ginsburg talked about the concept of tikkun olam that had become such a vital part of her heritage… Pulling out her pocket copy of America’s foundational legal text, she spoke of her great-granddaughter, saying that she would like to tell her that ‘your equality is a fundamental tenet of the United States.’ [Her plea] made clear the continuity of Ginsburg’s commitment to equal justice. The struggle to repair the world never ceases.”