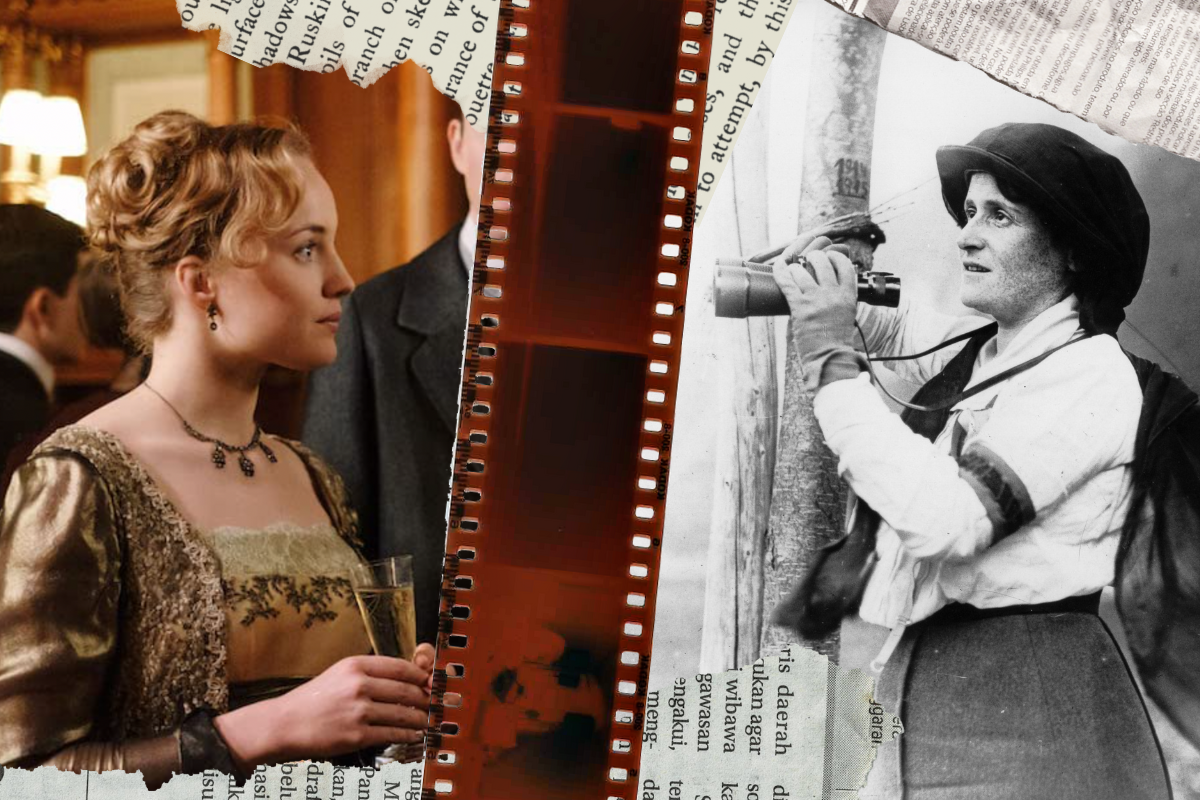

Mystery lovers and devotees of costume drama, rejoice! “Vienna Blood” — the most Jewish non-Jewish show on TV — is back for a third season on PBS’s flagship Sunday evening lineup. As I’ve previously written, the show deftly portrays the complexity of European Jewish lives before the Holocaust. Now, the classic odd couple of Inspector Oskar Reinhardt (gruff and caring) and Jewish Freudian Dr. Max Liebermann (aloof and insightful) have returned to investigate grisly murders in Edwardian-era Vienna.

In season three, Max’s ex-fiancée Clara Weiss has decided that two broken engagements is quite enough. She takes her life in an entirely new direction, becoming a freelance newspaper writer whose work winds up colliding with one of Max and Oskar’s murder investigations. Wouldn’t you just know, Clara and Max wind up uneasily spending time together and helping each other out to report on and catch the bad guy(s).

Most interestingly, Clara’s welcome character development is rooted in the real life and times of Alice Schalek, a Jewish journalist and photojournalist of the era, who was the first and only female journalist to register with the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s War Office when the First World War broke out in 1914, eventually earning a medal for her work and bravery. A curious and passionate world traveler, Schalek’s career as a journalist and travel writer took her to India, South America, Japan, Korea and Manchuria. Arrested by the Gestapo in 1939, Schalek took advantage of her eventual release by fleeing Austria for a safer life in the U.S.

Alice Schalek was born into an upper middle-class Jewish Viennese family not unlike Max’s — apparently quite assimilated, with a successful businessman for a father — in 1874. Her father Heinrich’s business was Austria’s first newspaper advertising company. While his press connections may have played a role in Alice’s professional success initially, her creativity and prolific output in fiction, reporting, nonfiction and photography quickly stood out on their own merits.

After launching her publishing career as a widely praised novelist under the pseudonym Paul Michaely, Schalek joined the staff of the Viennese newspaper Neue Freie Presse in 1903, writing for their feuilleton section (a newspaper supplement covering cultural criticism, city news and gossip, and current fashion trends akin to the New York Times’s Styles section and The New Yorker’s Talk of the Town). Schalek was soon promoted to editor of the feuilleton section, and continued to write and edit work for the paper until 1934.

Given the fictional Clara Weiss’s gender and longstanding interests in fashion and culture, it’s likely that her initial freelance assignments — to interview fashion designer Kristina Vogel and to cover the premiere of the silent film “Queen of Carthage” — would be slated for her paper’s feuilleton section, too. In the first season of “Vienna Blood,” Clara asks Max to confide in and trust her to assist in his investigations, a move which at the time proved too dangerous to pursue and prompted her to break off their brief, mismatched engagement. Two years later, working as a journalist with Max on his and Oskar’s cases is a safer way for her to follow her strong story-seeking instincts. Her professional interest in the city’s seedier goings-on also puts her on firmer, more collegial ground with Max.

Schalek’s tenure as a war correspondent combined many of her professional and personal interests. By 1915, she was already an experienced journalist, and though her photography skills — despite nearly a decade of work as a travel writer — were not exceptional, they were very useful accompaniments to her interviews with soldiers in Galicia, Serbia and the mountainous Tyrol region, which straddles present-day Western Austria and Northern Italy. This was a happy assignment for the avid mountain climber, who was a member of a club for high altitude enthusiasts until Jews were banned from its membership in 1921.

In 1904, one year into Schalek’s tenure as a newspaper editor, she converted to Protestantism. We don’t know whether her conversion was driven by belief, the necessity she may have felt to fit in more easily in an antisemitic and sexist society (especially as a woman pursuing a life and career without marrying), or some combination of factors. While her Christianity — like her class status — may have been of some use socially and professionally, it did not protect her from viciously antisemitic attacks from fellow journalist Karl Kraus in his anti-war criticisms of her work, nor from her arrest by the Gestapo decades later. Though Schalek sued Kraus for libel in 1916, his widely-published attacks led to her dismissal from the War Information Office in 1917.

Schalek returned to some of her pre-war professional activities, particularly travel journalism, leading her to publish books on her journeys around the world. Her 1925 book, “Japan: The Land of Contrasts,” presents a nation and region in transition to modernity and Westernization, viewed from many angles. These sojourns also gave her an international perspective on women’s rights and roles in society, as she’d met with activists in both Japan and India.

Although many of us credit our Judaism with leading us to embrace progressive and anti-racist values, Schalek’s Genteel European Abroad writings reflect her embrace of Eurocentric and Orientalist views broadly common at the time. These include critical or condescending remarks about social conditions, politics and the arts, all of which she othered by comparing them with their European analogues. It’s a disappointing but helpful reminder that being an oppressed minority doesn’t automatically lead to solidarity with fellow oppressed minorities. Indeed, Schalek would have had a strong interest in maintaining what social standing and capital she had, even to the detriment of others.

1939 brought with it persecution by the Gestapo, who searched her apartment and found photographs from Tel Aviv which they interpreted as mocking Nazism. Schalek was arrested in March 1939 and held for several months before being released. She fled Austria, making a home for herself in New York, where she died in 1956.

Although gaps in knowledge about her Judaism and eventual conversion and her not-unexpected views on people of color are vexing, Alice Schalek’s accomplishments as an early 20th century pioneer of photography, athletics, documentary travelogues and war correspondence remain worthy of recognition, celebration and admiration. And they give us reason to look forward to her continued influence on Clara Weiss’s life and career in potential subsequent seasons of “Vienna Blood.”