On January 6, 2021, many of us took a deep sigh of relief when it was projected that both Rev. Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff would win their runoff elections, becoming the next two senators from Georgia and giving the Democrats a Senate majority while making history in the process.

Warnock and Ossoff campaigned together, and both of their elections are historic. Rev. Warnock’s election is particularly important: He becomes the first Black man to represent Georgia in the Senate, the first Black man popularly elected to his Senate seat from a state in the former Confederacy, and the 11th Black senator in U.S. history.

With the long history of violent white supremacy and brutality against Black people in the south, it’s an emotional and important win. “The other day, because this is America, the 82-year-old hands that used to pick somebody else’s cotton picked her youngest son to be a United States senator,” Warnock said in a victory speech early Wednesday morning. “Tonight, we proved with hope, hard work, and the people by our side, anything is possible.”

Ossoff, on the other hand, becomes the state’s first Jewish senator — joining a large group of Jewish senators, including new Senate Majority (!!) Leader Chuck Schumer. On Twitter, many people, in speaking about the history-making nature of this election, started posting about Leo Frank, a Georgian Jewish man lynched in 1915 in Marietta, Georgia.

Who was Leo Frank, and why are people talking about him in reference to the Georgia runoffs? We got you.

Who was Leo Frank?

Let’s do a super quick biography: Leo Frank was born in Cuero, Texas to two Jewish parents; they moved to Brooklyn when he was 3 months old. Leo grew up in Brooklyn, attended school in New York, and graduated from Pratt Institute in 1902 and then Cornell in 1906. In 1908, he moved to Atlanta, Georgia and became superintendent of the National Pencil Company factory. In 1910, he married a Jewish woman, Lucille Selig.

Notably, Frank was involved in Jewish life in Georgia, and in 1912, he was elected president of the Atlanta chapter of B’nai B’rith. B’nai B’rith was founded in 1843 as a Jewish fraternal organization — basically a society of Jewish dudes. Their first action as an organization was establishing the first Jewish community center in the U.S.: Covenant Hall in New York City, then the first Jewish public library. B’nai B’rith has since evolved into a service organization, working to advocate for the Jewish community in general.

But let’s get back to Leo Frank: In 1913, Frank was convicted of raping and murdering Mary Phagan, a 13-year-old employed at the National Pencil Company factory (that Frank managed, remember).

What happened?!?!

Here’s a quick recap of the case from My Jewish Learning:

“Little Mary Phagan,” as she became known, left home on the morning of April 26 to pick up her wages at the pencil factory and view Atlanta’s Confederate Day parade. She never returned home.

The next day, the factory night watchman found her bloody, sawdust-covered body in the factory basement. When the police asked Leo Frank, who had just completed a term as president of the Atlanta chapter of B’nai B’rith to view her body, Frank became agitated. He confirmed personally paying Mary her wages but could not say where she went next. Frank, the last to admit seeing Mary alive, became the prime suspect.

Georgia’s solicitor general, Hugh Dorsey, sought a grand jury indictment against Frank. Rumor circulated that Mary had been sexually assaulted. Factory employees offered apparently false testimony that Frank had made sexual advances toward them. The madam of a house of ill repute claimed that Frank had phoned her several times, seeking a room for himself and a young girl.

In this era, the cult of Southern chivalry made it a “hanging crime” for African-American males to have sexual contact with the “flower of white womanhood.” The accusations against Frank, a Northern-born, college-educated Jew, proved equally inflammatory.

Frank, throughout the accusation and trial, proclaimed his innocence. The prosecution based the majority of its case on the testimony of the factory’s janitor, Jim Conley. Historians today believe Conley to be the actual murderer of Mary — he was seen washing blood off his shirt. Meanwhile, Frank’s housekeeper placed him at home at the time of the murder.

During the trial, Frank’s defense attorney, Reuben Arnold, argued that antisemitism was the reason he was on trial (and sorta leaned into said antisemitism): Frank was accused because he “comes from a race of people that have made money. If Frank hadn’t been a Jew he never would have been prosecuted.” The prosecutor Hugh Dorsey, too, spoke of Frank’s Jewishness, saying, “This great people rises to heights sublime, but they can sink to the depths of degradation too.”

Ultimately, the jury found Frank guilty in four hours and sentenced him to death.

Historian Leonard Dinnerstein writes that one juror said before his selection: “I am glad they indicted the God damn Jew. They ought to take him out and lynch him. And if I get on that jury, I’ll hang that Jew for sure.”

What happened next?

Frank tried to appeal the sentence, yet Georgia’s higher courts and the U.S. Supreme Court refused to reopen the case. Georgia Governor Frank Slaton then was Frank’s last hope: After reviewing the case, and the trial judge’s recommendation, Slaton commuted Frank’s sentence from death to life imprisonment.

When that news — Frank was not to die — came out, a mob of 5,000 people protested Slaton’s home. Slaton was not intimidated; he believed Conley to be the actual murderer, and privately told friends he would have issued a full pardon.

“Two thousand years ago,” he wrote, referencing Jesus, “another Governor washed his hands and turned over a Jew to a mob. For two thousand years that governor’s name has been accursed. If today another Jew [Leo Frank] were lying in his grave because I had failed to do my duty, I would all through life find his blood on my hands and would consider myself an assassin through cowardice.”

What about Frank’s lynching?

We’ll let MJL describe, again:

On August 17, 1915, a group of 25 men — described by peers as “sober, intelligent, of established good name and character”— stormed the prison hospital where Leo Frank was recovering from having his throat slashed by a fellow inmate. They kidnapped Frank, drove him more than 100 miles to Mary Phagan’s hometown of Marietta, Georgia, and hanged him from a tree.

Frank conducted himself with dignity, calmly proclaiming his innocence.

Townsfolk were proudly photographed beneath Frank’s swinging corpse, pictures still valued today by their descendants. When his term expired a year later, Slaton did not run for reelection.

How did the Jewish community react?

Soon, Jewish families began fleeing Atlanta, fearing rising antisemitism. In the aftermath, around half of Georgia’s 3,000 Jews left the state.

“What it did to Southern Jews can’t be discounted,” Steve Oney, a writer who has spent extensive time writing about Frank, explained to the Forward. “It drove them into a state of denial about their Judaism. They became even more assimilated, anti-Israel, Episcopalian. The Temple did away with chupahs at weddings — anything that would draw attention.”

The Anti-Defamation League was founded the same year as the trial of Leo Frank, but Frank was not the catalyst for the organization. Rather, “the trial served as a confirmation… that American Jews needed an institution to combat antisemitism.”

What is the legacy of Leo Frank?

In 1986, the State of Georgia issued a posthumous pardon, and there is now a historical marker where Frank was hanged.

The pardon said: “Without attempting to address the question of guilt or innocence, and in recognition of the State’s failure to protect the person of Leo M. Frank and thereby preserve his opportunity for continued legal appeal of his conviction, and in recognition of the State’s failure to bring his killers to justice, and as an effort to heal old wounds, the State Board of Pardons and Paroles, in compliance with its Constitutional and statutory authority, hereby grants to Leo M. Frank a Pardon.”

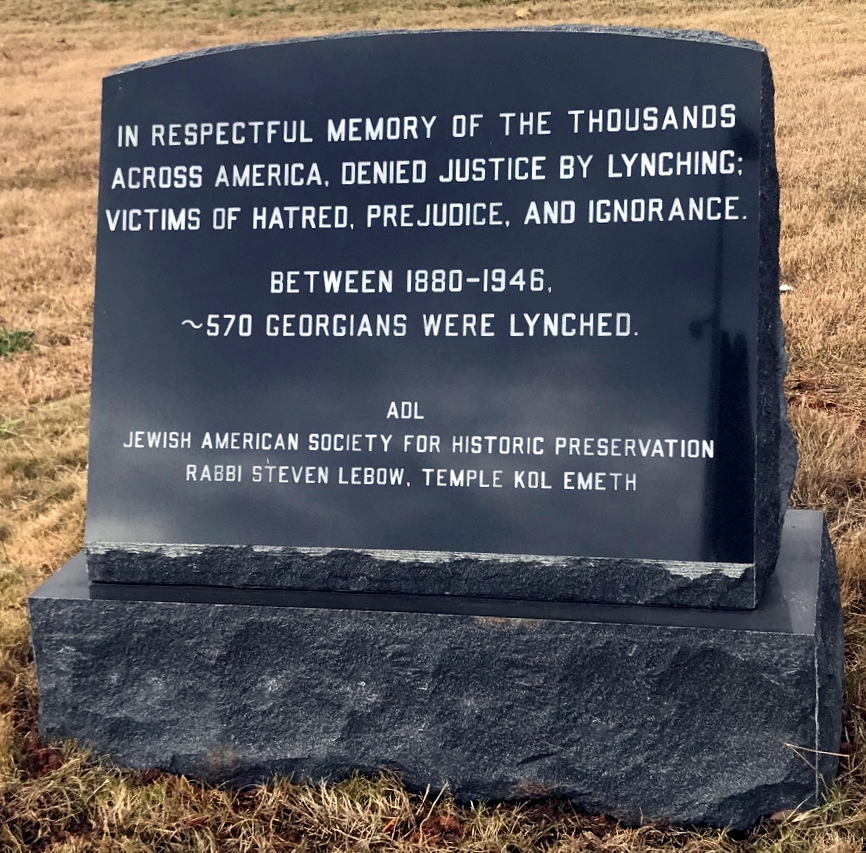

In 2018, the first national anti-lynching memorial was placed in Marietta by the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation, the ADL, and Temple Kol Emeth. The text reads: “In Respectful Memory of the Thousands Across America, Denied Justice by Lynching; Victims of Hatred, Prejudice and Ignorance. Between 1880-1946, ~570 Georgians Were Lynched.”

To be clear: Leo Frank is the only Jewish person lynched in American history, and lynchings predominately targeted Black Americans. From 1882-1968, 4,743 lynchings occurred in the U.S., and of that number, 3,446 were of Black people. It’s also very likely that many lynchings went unreported. And of the white people lynched, they were often lynched for helping Black Americans.

So why are people talking about this now in relation to Jon Ossoff?

Leo Frank was the only Jewish man lynched in America, and it happened in Georgia. Jon Ossoff is now elected as a Jewish man from Georgia, becoming the first Jewish Senator from the Deep South since Reconstruction.

Leo Frank, 31-year-old president of the Atlanta chapter of B’nai B’rith, was lynched in Marietta, Georgia, 105 years ago last summer, causing many fellow Jews to leave the state. This is one important backstory of Jon Ossoff’s campaign to become a U.S. Senator tonight. pic.twitter.com/pjO6YwCP8c

— Michael Beschloss (@BeschlossDC) January 6, 2021

https://twitter.com/koshersemite/status/1346697038344433671?s=20

https://twitter.com/schxleo/status/1346661820220796932?s=20

It’s exciting, it’s historic, and it’s proof that while it may be taking way too long, progress against hate and bigotry is possible.