Last Wednesday, January 6, 2021, a pro-Trump mob attempted a coup in Washington, D.C. with the goal of stopping the confirmation of President-elect Joe Biden. It failed — Congress was able to reconvene a few hours later, after its members donned gas masks and went into hiding, in order to officially confirm Biden. But many are saying just because one coup attempt failed, that doesn’t mean we’re quite in the clear.

Why? Well, let’s look to history. In November 1923, Hitler tried to use the Nazi Party to take over Munich and then march on Berlin to take over all of Germany in what is called the Beer Hall Putsch. Though that too failed, it eventually led to the rise of Hitler a decade later — and the total transformation of the German right.

So, what exactly happened with Hitler’s first coup attempt, and why are so many folks talking about it now? Let’s get into it, shall we?

First: What is a “putsch”?

Putsch, a German word, originally translated to “knock” or “thrust,” but starting with the Kapp Putsch of 1920, it became an English term to signify an attempted overthrow of a government, otherwise known as a coup.

What was the Kapp Putsch?

In March 1920, right-wing officer Wolfgang Kapp declared himself the new dictator of Germany, disavowing the elected President, Friedrich Ebert, and his Chancellor, Philipp Scheidemann. He abolished all democratic institutions and the German government fled Berlin. Yet, the coup failed after a few days when German workers declared a general strike and everyday life was shut down.

- Photograph of a demonstration in Cologne, Germany against the Kapp-Lüttwitz Putsch (1920)

The Kapp Putsch failed, yet it had a key implication: The German military was not going to intervene when there were attempts to overthrow the Weimar Republic. Essentially, when Ebert (German president) asked the military for help in maintaining control, he was told, “the Army does not fire on other Army units.” So, as the Holocaust Encyclopedia writes, “The military, therefore, made it clear that they were happy to fight the left but would not take arms against the right-wing.”

What was the Beer Hall Putsch?

In November 1923, the National Socialist Workers Party, also known as the Nazi Party, organized a coup led by Adolf Hitler. Hitler teamed up with World War I military hero Erich Ludendorff.

Wait, who is Ludendorff?

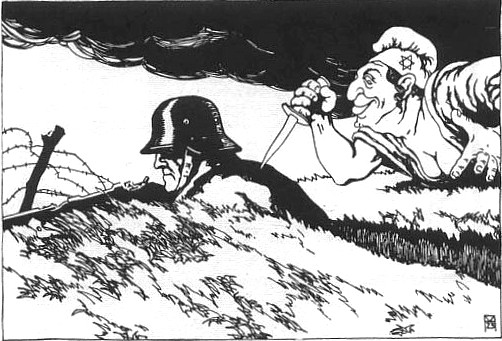

He was a military general. Notably, after WWI, Ludendorff became a big nationalist leader and propagated the “stab-in-the-back” myth, an antisemitic conspiracy theory that started spreading in 1918 that claimed Jews were the reason the German Army lost the war. Essentially, the belief goes, the army didn’t lose the war; rather, civilians on the home front — Jews, especially — betrayed the army, causing them to lose.

- Illustration of the “Stab-in-the-Back” legend from an Austrian postcard, 1919

When the Nazi Party came to power, this myth was a part of their telling of the story of recent Germany history, saying the Weimar Republic was caused by “November criminals” — AKA the Jews who stabbed the German army in the back. We can’t believe we have to write this, but this myth was completely and utterly false; the German army simply lost the war, overwhelmed and overpowered.

Ludendorff also participated in the 1920 Kapp Putsch.

Okay, back to the Beer Hall Putsch.

Hitler, Ludendorff, and the Nazis planned to take over the city of Munich, then the state of Bavaria, then march on Berlin and take over Germany. They were modeling this on Italian fascist Benito Mussolini’s “March on Rome,” which brought fascists to power in Italy in October 1922 without military support.

On November 9, 1923, Hitler and Ludendorff marched on downtown Munich, where Gustav von Kahr, the state commissioner of Bavaria (the state Munich was in), was speaking at Bürgerbräukeller, one of the biggest beer halls in Munich. Von Kahr was with Armed Forces General Otto von Lossow and State Police Chief Hans Ritter von Seisser (which we’ll call the “triumvirate” from here on out, referring to these three key Bavarian leaders).

Around 600 Nazi party members surrounded the beer hall. Then, Hitler and key associates — like Hermann Göring and Rudolf Hess — marched through the beer hall and shouted, “The national revolution has broken out!” They forced the triumvirate into a room in order to pressure them to back their putsch.

Göring gave a speech, then Hitler did, saying their action was not against the Bavarian police, but rather, “the Berlin Jew government and the November criminals of 1918.” (Remember, the November criminals = the “stab-in-the-back” myth.)

When Ludendorff arrived, instead of pressuring the triumvirate of Bavarian leaders to continue to support them, he released them. (One of many mistakes they made that evening.) After the triumvirate was free, they denounced the overthrow and ordered armed forces (the police and the military) to suppress it.

There was chaos and disorganization, and Hitler then tried to lead 2,000 Nazis in a march on downtown Munich, where they were met by local police forces and dispersed. Hitler was arrested two days later and charged with high treason.

What were the consequences of the Beer Hall Putsch?

A few key things happened: One, it was the first time the Nazi Party had national exposure, and in some senses, it launched Hitler’s national political career in Germany. It gave the Nazis what some call a “propaganda” victory.

Hitler was sentenced to five years in prison, but he was released after eight months for good behavior. While serving, he wrote Mein Kampf. The main argument of his book? The “Jewish peril,” AKA an antisemitic conspiracy theory that Jews control the world.

- The accused in the Hitler Putsch Trial, (from left) Pernet, Weber, Frick, Kriebel, Ludendorff, Hitler, Bruekner, Roehm and Wagner ,1923/4

It also led Hitler and others on the German right to shift their thinking in coming to power. Instead of by violence, they decided to try through legal means; they wanted to overthrow from within by winning national elections. Their new path to victory: through the system.

As the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s Holocaust Encyclopedia points out, “The experience taught Hitler that an attempt to overthrow the state by force would bring forth a military response in its defense. From that time on, he was committed to taking advantage of the Weimar democracy to subvert the state from within. He sought to come to power by means of the popular vote. He aimed to influence that vote by using the freedoms of speech and assembly guaranteed by the Weimar Republic.”

In 1933, he achieved his goals and was appointed chancellor — starting the rise of Nazi Germany.

As the Nazis gained power, the date of the putsch, November 9, became known as the Reich Day of Mourning (Reichstrauertag).

What are the parallels to 2021? What are people saying?

There are clear parallels.

Historian Michael Brenner writes in The Washington Post, “What at first blush looked like a failed coup proved successful in the long run because of a justice system that was blind in its right eye and conservative political leaders who fueled the myths that Hitler had tapped into, planted the seeds of political polarization and discredited the legitimacy of elected officials. These leaders were also convinced that they could use Hitler and his mass movement as a vehicle to stay in power, even though they despised him and looked down on him as an upstart. His vice-chancellor, Franz von Papen of the Catholic Center Party, famously claimed he and his moderate cabinet members would keep Hitler and his Nazi troops in check. Von Papen lost this game and so did all the other enablers who made Hitler’s rise possible. But they didn’t decisively move to squelch his movement during the 1920s when they had the opportunity.”

Essentially: Hitler and his followers were just given a tap on the wrist, and this leniency allowed Hitler to rise to power in under a decade, setting the stage for Nazi Germany and the horrors of the Holocaust.

Even though the putsch failed, it’s what happened next that matters.

As Nathan J. Robinson writes in Current Affairs, “The ‘Beer Hall Putsch’ was probably never going to succeed, because it was disorganized and the Nazi Party was weak in 1923. But it was a terrifying sign that a far-right element was gathering strength, one that did not respect the existing liberal regime’s right to rule and would use whatever means were at its disposal to take power. Not everyone recognized that sign at the time. The New York Times ran the headline ‘Hitler Virtually Eliminated‘ and suggesting that with Hitler’s jail sentence, the courts had put the far right out of commission once and for all.”

In 2021, Robinson continues, “The New York Times quickly published an article calling the events the ‘end of the Trump era’ and ‘a last-ditch act of desperation from a camp facing political eviction.’ I am not so sure about this. Their tone reminds me too much of the one they took in 1923 when they wrote that ‘any prospect of Hitler playing a leading part in Bavarian politics appears to have vanished…’ I think it is fully possible that Trump will be back.”

What’s Twitter saying?

Here are some reactions:

Just your morning reminder that the Beer Hall Putsch and March on Rome were also considered farcical affairs at the time.

— Sam C H 🏳️🌈 (@schuneke) January 7, 2021

this has already gone 100x as far as the Beer Hall Putsch. Hitler didn't even make it to the regional capital building in 1923

— ryan cooper (@ryanlcooper) January 6, 2021

It's important to point out that the Beer Hall Putsch and the March on Rome were both just as comitragically dumb and as today's events and yet the Nazis and the Fascists still took power.

— Terrence Peterson (@dr_tgpeterson) January 6, 2021

TL;DR

The Beer Hall Putsch of 1923 failed, yes, but the Nazis still came to power not long after that. And so, many believe the attempted coup in Washington, D.C. in January 2021 likely won’t be the last we’ll see of this alliance of the far right here in the United States.