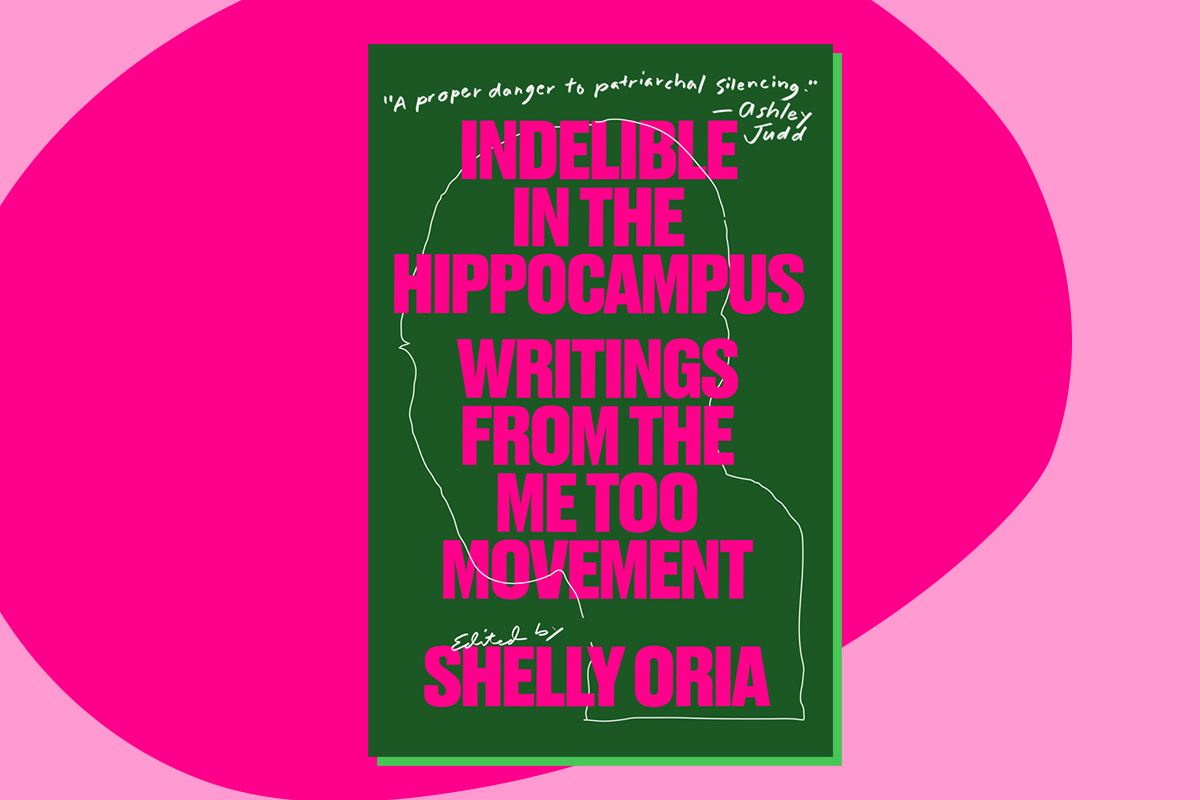

“Indelible in the hippocampus is the laughter. The uproarious laughter between the two, and their having fun at my expense,” Dr. Christine Blasey Ford testified to Congress on September 27, 2018, about the night Brett Kavanaugh allegedly assaulted her. The testimony took place during the hearings for Kavanaugh’s nomination to the Supreme Court. During that September, Israeli-American author Shelly Oria was editing a collection of writings about the #MeToo movement — Dr. Blasey Ford’s powerful words eventually became the title. Indelible in the Hippocampus: Writings from the Me Too Movement gathers 22 writers to address the movement, with a mix of non-fiction, fiction, and poetry.

“Working on Indelible in the Hippocampus — compiling the book, editing the pieces, and writing my own — felt like a doing at a time when I was desperate for exactly that, for some type of action I could take,” Oria explained over e-mail. “Having grown up in Israel, I find protesting extremely hard, at times impossible — I grew up believing this type of action mattered, and while my brain still believes that, my body hasn’t in many years. That’s not the experience of all Israelis or all liberal Israelis, of course, but it is mine. In our current political reality in the U.S., I’ve forced myself to march time and again — to show up, in my abled, privileged body — but it felt excruciating every time (and lonely, too, since most people I know feel empowered in those environments). But writing, and putting together this book: that’s felt and still feels like the type of protest I can show up for again and again and never tire, the type of protest I can even lead, my own tiny revolution.”

Over e-mail, we asked five of the Jewish contributors to Indelible — Lynn Melnick, Rebecca Schiff, Diana Spechler, Quito Ziegler, and Courtney Zoffness — to talk about their experiences of writing about #MeToo, this era, and how their identity as a Jewish person shapes their writing.

What does writing about the #MeToo movement mean to you?

Lynn Melnick: I’ve always written about rape culture and violence against women, specific to my personal history but also to the culture in general. Now that these subjects are more widely written about and acknowledged, it feels a little less vulnerable to speak up, but it’s still difficult and it’s still very important to do so.

Diana Spechler: We have men in positions of incomprehensible power in this country — occupying the White House, sitting on the Supreme Court, presiding over entire industries — who have been accused of raping, assaulting, and harassing women. As the systems that support them continue to fail us, the #MeToo movement restores some of our agency. Maybe these gross men still get to be our boss, our colleague, President of the United States; maybe they’ll never go to prison or even take a pay cut. But at least we have a microphone now. I love how that hashtag has amplified our voices.

Rebecca Schiff: I question if there’s a way to write fiction about topical issues in a way that still feels authentic, if there’s room for playfulness or inventiveness when a political discourse has already been laid down. My first thought when I heard about the Indelible anthology was that I didn’t have a #MeToo story to share, but then I got interested in a character who used to be political, but has decided she’s going to “sit out” the #MeToo movement.

Courney Zoffness: It means participation in a conversation that has already lead to tangible change — more women being believed and more men being held accountable. It also means ensuring our voices stay loud.

Quito Ziegler: My gender transition taught me to question everything about how our culture is structured, dating back to the Western notion of binary gender. It was part of my personal reckoning, somewhere in the long healing process that being a survivor entails. Somehow reconciling my experiences with violence and my non-binary gender also meant reconciling myself with the violence that had happened on this land, to people who acknowledged, understood, and respected my gender more than the future Americans did.

How do you care for yourself while writing about these topics?

Spechler: The writing is the self-care.

Melnick: I don’t know. I haven’t done a great job of it. My last book was all about rape culture and violence and promoting it was important but it also took a lot out of me, emotionally, to continuously stand up in front of people and read and answer questions about my trauma history. Well, okay, maybe I did find a way to care for myself: I decided to spend all of 2019 writing about Dolly Parton! And, for the most part, that’s what I’ve done. It’s been freakin’ fantastic.

What does the #MeToo reckoning look like for you? In Judaism the concept of atonement is a big one — is it possible for someone to atone for sexual misconduct? Is it possible to forgive?

Zoffness: The #MeToo movement’s wide net supports those who’ve endured everything from grotesque sexual violence to daily sexist slights. I believe the question of forgiveness is up to each survivor — and true atonement is up to each perpetrator. Insofar as a reckoning, I think the first step is to hear and accept the range of women’s experiences. There are far more good men than dangerous ones, and we need a community of allies, of people willing to change the tenor of the conversation and intervene when men behave badly.

Melnick: Lately I’ve been thinking a lot about this question of atonement. In recent years there’s been a move to sort of banish people from spaces when they act in harmful ways. And I think sometimes those people need to be gone, for the protection of others! I think it’s always important to call out injustice and reduce harm when we witness it. But I also think there’s got to be a way for people to truly atone for bad actions. There has to be a path forward. Restorative justice is a term that I’ve seen lately often misused, but it is about repairing the harm caused, in a way that very much centers the victim but also includes the perpetrator. The concept of repair is a very Jewish one, I think.

Spechler: Assailants should absolutely atone, ideally not to score points or evade consequences, but out of remorse. As for forgiveness, that’s up to each victim.

Schiff: I’m not sure. I’m not drawn to the concept of atonement (or Yom Kippur), but I’m interested in a communication model that offers people relief from suffering. (I just watched the Michael Jackson documentary and it struck me how he was nowhere near atonement because atoning requires introspection and honesty. I wondered if him atoning would have made a difference to the lives of the men he abused.) I guess I’m most interested in the truth, and if forgiveness comes out of telling the truth, that’s a bonus.

In the future, what do you think the defining moment of this era will be?

Melnick: Like the way Congress’s inaction on gun control after Newtown was a defining moment of inaction on gun control, I feel like Dr. Christine Blasey Ford’s testimony and treatment before Congress will be a defining moment of inaction in regards to the #MeToo movement. I mean, not to be a pessimist, because I’m possibly a secret optimist, but I think that particular moment points to how hard change is. I’ve been fighting against rape culture almost my whole life; it’s slow work that a hashtag isn’t going to change quickly. That said, I’m grateful for the new awareness and efforts, and I still believe change is coming.

Spechler: I often think about Emma González giving that “We Call B.S.” speech right after the Parkland shooting. It wasn’t about #MeToo, but it could have been — she was tough as hell, taking on power structures that had almost killed her. I have never seen anything encapsulate the zeitgeist quite like that speech did.

Zoffness: I hope it will be the election of a female president.

How does your identity as a Jewish person shape how you think and write about #MeToo?

Melnick: Being culturally Jewish is a big part of my identity, so I can’t really separate it from my writing on rape culture anymore. I recently completed a manuscript — which will hopefully become my next book — that, in part, takes on the issue of rape culture and misogyny within Judaism. Growing up, I was often appalled and confused by the sexism in the religion, and the hypocrisy about it, even within the more liberal Jewish communities, but I didn’t know how to talk or even think about it. My new poems are an attempt to think and write my way through these complicated issues. No culture or community is immune to rape culture and misogyny.

Spechler: As Jews, we’re raised on “Never Again.” We learn in detail about the genocide of our people in Hitler’s Europe, about the way Jews have been persecuted and murdered all over the world throughout history, all those dark manifestations of power and greed and hate. My connection to that history predisposes me to speaking up.

Ziegler: Every week at services, Jews worldwide repeat the same stories, seeking new meaning in stories that perpetuate patriarchy. I deeply appreciate the sacredness of prayer, but at some point when do we switch up the script? The idea of gender as binary. The idea of God as Lord, as king. The idea of Jews as chosen people. These narratives are harmful in ways that, ultimately, make it hard for me to see beyond them, but make it easy to perpetuate lies that uphold white supremacist patriarchal capitalism and the continued colonization of Palestine. Other narratives are rooted in a different vision of humanity, one that doesn’t force people to compromise ideals on the daily in order to meet basic needs. None of my objections are new, and I respect Jewish feminists who have sought to reclaim stories of powerful femmes throughout history and the ancient Talmudic scholars who supposed that gender was fluid — ideas that never quite made it into my Hebrew School curriculum. But there are other stories to tell, to repeat. Stories that teach us different kinds of lessons and ways of being, different ways of treating each other and the other forms of life we co-exist with.

Zoffness: I was raised on stories of anti-Semitism and religious persecution and the post-Holocaust mantra “Never Again.” We’re seeing ample evidence that white supremacy, the kind that fed Nazi-style eugenics, is alive and well in this country. Calling out injustice and defending vulnerable populations — whether with our words, our voices, our votes — is one of the most important roles we can play as citizens, and humans.

Indelible in the Hippocampus is out September 10, 2019.