Over the weekend, the New York Times published an interview with Alice Walker in which she recommended the book “And the Truth Shall Set You Free” by David Icke. This book is extreme anti-Semitic propaganda built on Elders of Zion conspiracies. While many have known about Alice Walker’s anti-Semitism for a long time, this interview set off a public conversation about Walker’s anti-Semitic views.

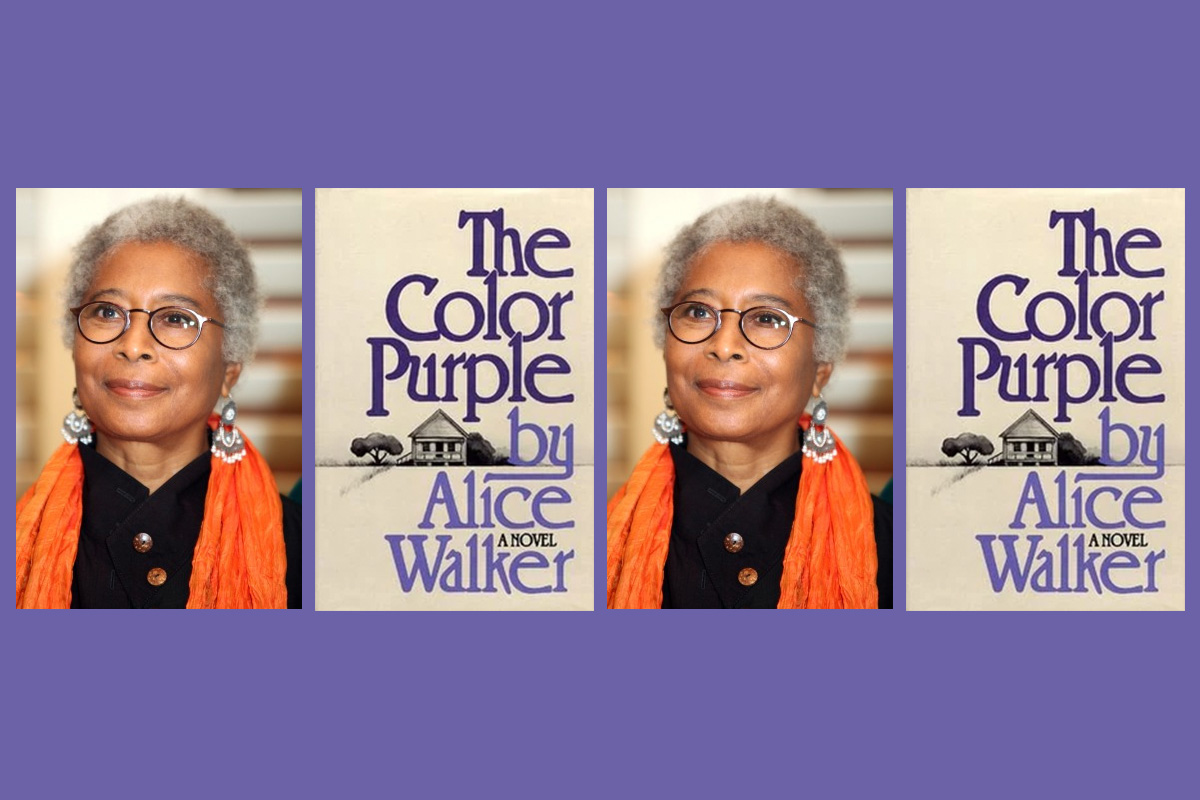

I first learned of Alice Walker’s anti-Semitism in 2012, when I read she declined to have The Color Purple published in Hebrew. Walker claimed this decision was based on Israel’s occupation in Gaza, but she had no problem writing the book in English or having it translated into other languages spoken by people with histories of oppression. This statement associated anyone who spoke Hebrew with the Israeli government and denied an exchange of ideas that arguably could support Walker’s cause for Palestinians. Walker also has a history of promoting Icke as far back as 2013.

Walker’s anti-Semitism is made more complicated and tragic when we remember that her own daughter, Rebecca Walker, is Jewish. Rebecca’s father, Melvyn Rosenman Leventhal, is a Jewish attorney who got divorced from Walker seven years after Rebecca’s birth. Rebecca Walker wrote Black, White, and Jewish: Autobiography of a Shifting Self in 2000. She and her mother have been estranged since the birth of Rebecca’s son. One wonders how this relationship impacts Alice Walker’s anti-Semitism. Rebecca has spoken publicly about her mother’s neglect and prioritizing of ideology over relationships.

Despite this knowledge, it never occurred to me to not read The Color Purple or be grateful for Walker’s other work. I was raised on Alice Walker by my second wave feminist mother. The Color Purple and Warrior Marks (a book written with Pratibha Parmar on female genital mutilation in Africa) were bibles in my house. The Color Purple showed me a world where women were surviving the abuse of men and opened me up to what I now know as intersectional feminism. Walker’s work allowed me as a young girl to read about the experiences of women vastly different than my own, whose fight I wanted to be part of.

Alice Walker was also instrumental in bringing Zora Neale Hurston’s work to a larger audience. When Walker first wrote about Hurston in 1979, all of Hurston’s books were out of print. I can only imagine what her work has meant to black women. In a nuanced thread clearly calling out Alice walker’s anti-Semitism, Evette Dionne described the importance of Alice Walker:

I don’t believe in canceling people, especially the person who wrote The Color Purple, put a marker on Zora Neale Hurston’s grave, and singlehandedly revived Zora’s career. We would not be reading Zora now if Alice had not worked to get Zora’s work back in print.

— Evette Dionne 🤷🏾♀️ (@freeblackgirl) December 18, 2018

Unfortunately, like most examples of anti-Semitism, the online discussion of Alice Walker quickly pivoted to justifying it through blame on Israel. As if somehow it would be okay to spread Elders of Zion conspiracy theories if one is trying to help Palestinians. There are so many problems with this — including that Jews and the Israeli government are not synonymous. Perpetuating anti-Semitism does nothing to tackle the Israeli government’s policies but does cause real harm to Jews around the world. As Rebecca Pierce, a black and Jewish woman, emphasized on Twitter, supporting anti-Semitic conspiracy theories also support the white supremacist power structure that Walker has been fighting against her whole life.

This Alice Walker thing is really fucking sad and it makes me angry that she can’t see that the anti-Jewish conspiracies she uplifted and adopted are part of the same white supremacist power structure she so deftly fought through her written work in the past

— Rebecca Pierce🕸 (@aptly_engineerd) December 17, 2018

So where does this all leave us, the people who admire Walker’s writing and activism but cannot stand for anti-Semitism?

One of the most important parts of Judaism, for me, is the ability to embrace argument and contradictory thoughts. While not true for all artists, to me it has always seemed imperative to speak about Walker’s anti-Semitism without throwing out the important work she’s done. As intersectional feminists, can we leave room for embracing the good done by a problematic person? As Jews, can we honor the human rights work done by Alice Walker without erasing her harmful views towards us?

Tema Smith, a black and Jewish woman, put it perfectly when she told me, “As the Jewish child of a black parent, it cuts especially deep to know that this is a woman who used her pen to wound her own Jewish daughter and people like her, and yet also a woman who has told stories like The Color Purple that must not be lost.”