This article originally appeared on Be’chol Lashon’s Jewish& blog on My Jewish Learning

Sitting shiva is intended to help us acknowledge that death is a natural part of life, nothing to be feared. But this death, this is not natural.

It’s a nightmare. The kind that shakes you to your core. The kind that leaves you feeling naked and alone. I am angry. I am grieving. The Black community is grieving. The Black people in your communities are grieving. Black Jews are grieving, and we need you to help us mourn.

Now more than ever, we should be using the traditional etiquette of shiva to reach out in love to Black people in our personal networks and communities.

- Call us. Reach out to us intentionally. Remind us we are not alone.

- Create space for our sadness and heartache.

- Listen in love and compassion.

- Honor our grief process without trying to constrain, correct, or fix it.

- Offer your unconditional support, presence, and love.

- Remind us to take care of ourselves physically, emotionally, and spiritually.

- Ask what you can do.

This wisdom exists because we understand the need for communal support in grief. This is a time to showcase your compassion. We cannot do this alone.

My heart has been warmed by peaceful protest and online activism declaring enough is enough. I have been granted moments of relief with the outpouring of love and support from colleagues and allies. I am proud to see communities coming together in solidarity. I am honored to take on the responsibility of furthering the pursuit of racial justice, the legacy of the Civil Rights Movement.

I do not want my children to inherit the world I inherited.

***

It is so hard to be safe and to feel safe as a Black person in the United States. I feel like I’m always on guard. Always mindful of how I speak, how I hold my body, when to give or avoid eye contact, how much public space I’m allowed to occupy because I want you to feel safe around me.

I try to be thoughtful with my words when I speak to you. I try to forgive you for your mistakes. I try to explain to you how much microaggressions hurt. I try to be an educator, to meet you where you are in hope that someday you will understand. I try to listen to you. I try to empathize with you and understand your good intentions. I try to create space for white discomfort, but in all of this I’ve forgotten to care for myself.

I am hurting. I can’t relax. I can’t sleep. I don’t want to eat. The pain is like a scream caught in my throat. I’m exhausted and I’m scared. I can’t breathe.

I forget that these are traumas for me and I try to keep my soul injury to myself, for you. In these moments I forget to let my guard down and share my pain. So it lies dormant and it festers, becoming ripe with rage.

I do racial justice work because it’s personal. I live across the street from the house my mother died in. Every day, I eat in the room where my grandfather lay dying for five months because my grandmother didn’t want him to continue to be abused in hospice care. In my 22 years of life, I have been to more funerals for my peers than I have been to graduations or weddings. I have watched mothers clean their babies’ blood off the street. I can drive through my city and show you the corners where people have been murdered. Where children have been murdered. My social media feed is perpetually full of “rest in power” because these things are happening every damn day.

This trauma surrounds me, replaying over and over with different names and faces. I hear you ask, “Have you seen the video yet?” You comment, “Which one?” “It’s awful.” “It’s horrible. #thoughtsandprayers #blm.”

No, I didn’t need to watch the recorded murder of George Floyd to know that he should still be here. I didn’t need to see yet another video normalizing brutality on black bodies to know that this was wrong. It’s not something I need to ‘get.’ This is something I live and I need you to be living it with me.

To be constantly surrounded by narratives of brutality on black bodies historically, experientially, and online is traumatic. I’m scared that there are people out there who cannot and will not see my humanity through my melanated skin.

My city of Oakland, my home is on fire, the streets have become war zones at nightfall. Infiltrators destroyed access to resources and services that are essential to Black lives. There are now Black elders without access to their medications. There are now Black homeless people who have nowhere safe to rest. I’m scared of the violence going through residential neighborhoods. I am hurt that bad actors tried to derail communal power and unity by causing confusion and chaos.

***

I’m committed to change. As we live through this moment, we must remember that the Civil Rights Movement didn’t happen overnight. In a world where everything seems to happen with such immediacy, it is easy for me to fall into a state of disillusionment when legislation doesn’t move at the speed of social media.

The protests are just one necessary piece of making change happen. We need you to vote. We need you to be committed to the process after the dust settles from mass protests. We need to take economic action. We need new laws, locally and nationally. We need anti-racist legislation. We need you to be committed even when it’s exhausting.

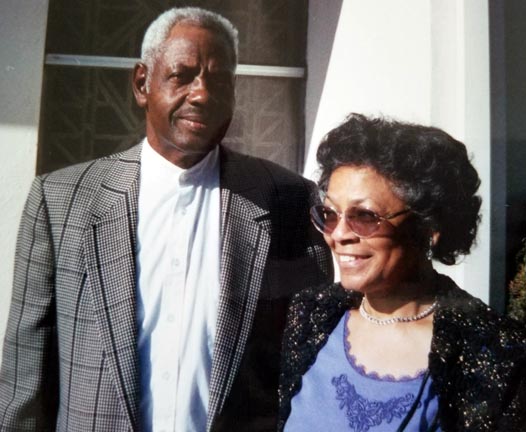

Even though these systems are imperfect and regressive legislation has sought to pervert them, the quality of life I have is substantially better than that of my mother or grandmother.

I don’t want my future children to always have to be on guard. I want them to have the full experience of youth, where no one shakes their belief that all things are possible. I want them to be able to dance big, laugh loud, and be equally protected by the Constitution and Bill of Rights.

In our collective memory, we have lived worse and we survived.

Gam zeh ya’avor, this too shall pass, and we shall overcome.

In the words of Kendrick Lamar, “We gon’ be alright.”