At a dinner party once, someone overheard me mention that my family migrated from Thessaloniki to the States before the war. He inserted himself into the conversation with glee to say “the Greek Jews have another name for the Sephardim, did you know that?” I did know that — not that it would stop a mansplainer from quaffing himself before a bunch of strangers at a dinner party.

My mother always said that if you asked her grandfather where he came from, he would shrug his shoulders, unable to answer. There were so many Greco-Turkish spats in those years that his village could have fallen on either sign of the border at any given moment in his childhood. As I say it: The food he ate was Greek; the hash he smoked was Turkish. The truth is, neither of those places would claim him or my family. Not Greek or Turkish. Only Jew.

It’s not an uncommon trope in the history of Jews. In one moment, we assimilate seamlessly, when in another, our otherness is outed in some way. Many are raising the roof as Yiddish has entered the world of Duolingo, while Ladino is so dead it likely can’t be revived outside of music or translation.

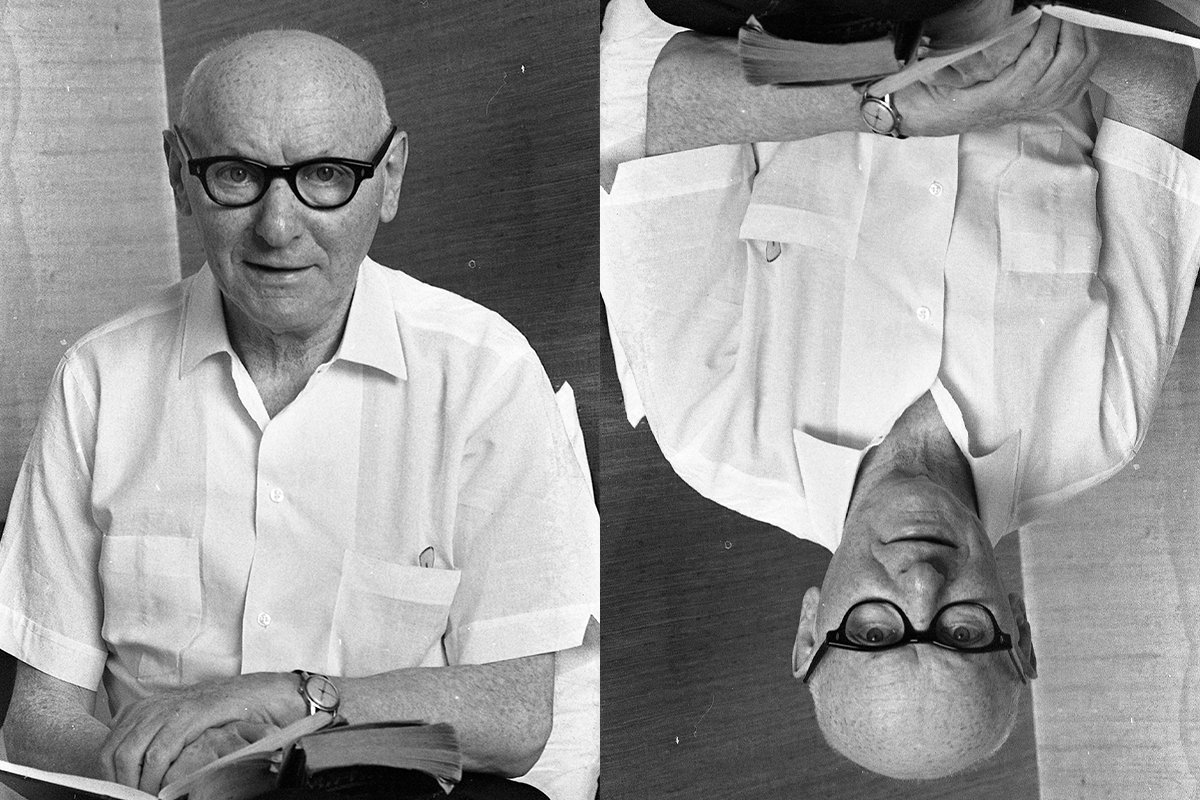

These otherwise niche grievances bear greater weight than we give them credit for in cultural fabric outside of Jewish communities, as I’ve been reminded by this past weekend’s New York Times Style Magazine. Sigrid Nunez’s essay “Just Passing Through” shows readers how the nature of making friendships and attachments to others changes over time, especially in a digital and now COVID-riddled world. In discussing “affecting moments shared between polite acquaintances and even people unlikely to meet again,” the novelist opens up the idea of friendship and writing with a nod to Isaac Bashevis Singer. “According to the Polish-American author Isaac Bashevis Singer, when you’re a doctor, God sends you patients, and when you’re a writer, he sends you a story.”

It’s hard to know if the erasure is Nunez’s or her editor’s, but either way, Nobel Prize winner Isaac Bashevis Singer should be identified as a Jew. The man wrote in Yiddish after all.

Yiddish, not Polish. He always said Yiddish was his mother tongue. And to what extent do the Polish even consider him Polish? Like my elders and the other living Jewish elders we know of, ethnicity excluded them from the claims to those nationalities.

Since the article only mentions Isaac Bashevis Singer in passing, it seems like a small error to kvetch over — roll your eyes and move on, right? And yet, this is not the first time in recent memory that erasing the Jewish identity of important public figures has occurred.

The announcement of Alejandro Majorkas’ nomination to Joe Biden’s cabinet and subsequent articles on mainstream publications — which rightly celebrated Majorkas as the first Latino and immigrant confirmed to serve as Secretary of Homeland Security — never mentioned he was also the first Sephardic Jew to do so. Though Alma covered it in retrospect, how many people outside of our niche corners of the internet still don’t know that there is finally significant representation at that political table? To what extent is it being intentionally swept out of the way? And why? What protocols are used at presiding media structures to use parts of identity for social gain or for keeping the waters calm? As antisemetic rhetoric is on the rise in this digitally politicized culture, what does this kind of erasure stand to mean?

In December 2019, a favorite actor of mine and my maternal grandmother’s passed away —Shelley Morrison. My grandma was already gone. Though she never encountered Will and Grace and the glory that was Shelley Morrison as Rosario, my grandmother loved her because she was the only Sephardic Jewish woman on screen who she could cling to. Yet when she passed away, she was described in the obituaries — like this one from the New York Times — as “a child of Spanish Immigrants.” Or this one in the Los Angeles Times where they mention she was born to Jews but spoke Spanish. But her parents spoke Ladino and so did she. And I felt whatever was left of that language I wish I knew died with her.

Isaac Bashevis Singer’s legacy — in literature and in the history of Jews — is beyond reproach. He was the leading figure of the Yiddish literary movement. It’s hard to imagine how the Yiddish revival of today could have happened without the attention his Nobel Prize in 1978 gave Yiddish literature.

Singer was born in 1903 in Warsaw. By the onset of World War I, he lived with his mother and brother in a shtetl in his mother’s hometown. His father was an Orthodox rabbi. Singer was so fearful of the threat of Germany that he emigrated to the States — his son and her mother went to Moscow then Palestine; the three wouldn’t be reunited for 20 years. Does this sound like a Polish-American’s life? Or the journey of a Jew, particularly in a time of great threat to Jews?

These themes are central to his books, too. For example, his National Book Award winning memoir, “A Day of Pleasure: Stories of a Boy Growing up in Warsaw,” presents what it was like to be a child of Warsaw’s Hasidic community growing up in a shtetl. The works speak for themselves — in Yiddish — and they will continue to, so long as we can read the language(s) they’ve been printed in.

It’s likely that the omission of a Jewish identity marker in Nunez’s article may have been a simple editorial note for conciseness. And while it may not be the most egregious hurt in the plight of the American Jew, it does point to a complex and liminal space that keeps getting overlooked.

Of course, there are all kinds of times when a Jew must decide to assimilate or hide: for survival, to avoid hostility, to deflect micro-aggressions, and so on. We choose to announce our identities based on the particular situation we find ourselves in, and based on our own personal levels of comfort. But how does omission or erasure by others participate in this anxiety and pain?

To what extent is assimilation assumed or expected? And to what extent are we to abide these terms? We owe more to the likes of Isaac Bashevis Singer, Shelley Morrison, Alejandro Majorkas, and so many more.