Ilana Masad’s debut novel, All My Mother’s Lovers, tells the tale of queer Jewish 27-year-old named Maggie. At the start of the novel, Maggie is in bed with her girlfriend-who-is-not-quite-her-girlfriend-yet when she gets a call from her brother telling her their mom has died in a car crash. She is numb, but immediately springs into action — buying her flights, figuring out the service at synagogue and shiva, and so on. When she gets to her parents’ house, her brother is acting out and her father is not functioning. Maggie finds letters that her mother left with her will, addressed to different men. After the funeral, she decides, she will set out and deliver them to their intended recipients.

The book takes place over just a few days, and focuses in on what it means to lose a loved one, as well as the complex relationships between mothers and daughters. It’s everything you want, and need, in a book that deals with grief and complicated families — all through a Jewish lens. I had the chance to ask Masad, an Israeli-American writer, a few questions over e-mail, where we talked about Jewish grief rituals, her own relationship with her Jewishness, and how she’s keeping calm with her debut novel coming out during a pandemic.

Why did you decide to structure the book like you did? (Set over the course of just a few days?)

Thank you for asking this question! I love thinking about form and structure. In this case, the structure of Maggie’s sections really grew out of her character’s needs and desires, which drove the plot’s constraints: Maggie has a job in St. Louis, and a girlfriend, and a whole life that she’s going to have to get back to, so her stay in California can’t be indefinite. Plus, Maggie’s so deeply uncomfortable witnessing her father’s grief, and she’s so resentful of what she believes is expected of her to do or be at the shiva, that I think she’d probably have found any excuse to get away from the house. Honestly, I’m grateful to Maggie for giving me this structure, because it allowed me to explore the rawness of new grief, the immediacy of it, which is very different from the way grief stretches — which it does, which it will for Maggie — over months and years.

I love how effortlessly inclusive the book was of all sorts of sexualities and relationships. Why was this important to you?

Because it’s the truth; human beings embody and practice all sorts of sexualities and relationships. There simply is no such thing as a truly homogenous set of people whose relationships are all alike, whose sexualities all operate the same way. And, I suppose, because I’m really tired of false notions of morality being somehow linked to the ways in which people choose to love one another.

I particularly loved the ending, which I won’t spoil for our readers. But suddenly, everything makes sense. Did you always know you were writing towards that?

I knew pretty early on the ending I was writing toward. I had a very particular conversation in mind that I knew Maggie and Peter would have, and there was a specific line of dialogue that I could picture Peter speaking, but everything around that was still kind of hazy. It took a little while before Peter revealed to me more about himself and the nature of his relationship with Iris, but it was still quite early in the process, so that for most of the time that I spent writing the book, I really did know where I was going (which was, I must say, a refreshing experience!).

What was the hardest part of writing All My Mother’s Lovers?

The middle part of most novels is really hard for me, because it feels slow and boring and dreadful and impossible, and I start to feel like there’s simply no point and I barely believe my characters and I start wondering what on earth I’m doing, pretending I’m a writer. But I also know it passes (this is the first novel I’ve sold but not the first I’ve written) and so I’m able, thank goodness, to push through that.

Can you talk about your own relationship to your Jewishness and Judaism?

How long do you have? Because we might be here all day! But no, seriously, it’s a very complicated question for me, because of where I grew up, because of what it was like being Jewish [in Israel] as opposed to what it’s like being Jewish [in America], because of how Jewishness became so conflated with language for me — a language that I miss every single day and that I ache for because it’s not a regular part of my life anymore — and how this part of my identity and language and self are so bound up in loving and grieving my father who died when I was 16. It’s complicated also because of politics and political rhetoric, the ways that a warped kind of Judaism on the one hand and anti-Semitism on the other have been weaponized both here and where I grew up as ways to excuse or explain violences perpetuated against Muslims, here, and Palestinians, there. It’s complicated because of imperialism, and because of the things I’ve worked to learn and unlearn over the years, and because of the grace I have been given in some spaces to be a person who has also lived through a complex and harrowing reality and the ways I’ve been shut down in other spaces even as I’ve tried to reckon with my own culpability.

At this point, I suppose, I’m at a place where I’m cautiously returning to all sorts of aspects of Judaism that I’ve missed and that for years I rejected and pushed away from, both out of a weird attempt to assimilate into a sort of flattened identity-less person who would never rock any boats (which, I learned, was impossible) and out discomfort with the idea of ritual. I’m an atheist, but I’ve learned by now that this needn’t actually preclude the practice of faith, at least for me; I don’t believe in a god, but I believe in human beings, and I believe in the power of belief. I’ve been thinking about things like history and legacy, and there’s something awe-inspiring to me about being part of a group who, for a couple millennia and more, have managed to keep alive and adapt a variety of traditions and rituals and — most importantly, to me — stories, even as various populations have kept trying to literally kill them. It’s humbling.

Do your own Jewish and queer identities intersect? If so, how?

I’m still trying to figure that out, actually! I think one of the key turning points in my desire to find my way back to my Jewishness was thinking about the idea of תיקון עולם [tikkun olam], which can be interpreted in all sorts of ways — overcoming idolatry, living well or kindly as a way of setting an example for others — but which I interpret a bit more actively than that. To me, tikkun olam is aligned with the idea of working for social, racial, and economic justice, and it’s inspiring to have models to follow in those Jewish people who have been involved in and supportive of every major fight that’s moved (inched) the needle forward toward equality in this country. Since my queer identity has long been deeply intertwined with my own political beliefs and practices and ideals, I feel like my Jewish self is slowly catching up, or connecting, or something.

The Jewish ritual of shiva plays a key part of the plot. What does sitting shiva mean to you?

Last year, in a class I was taking, the discussion of mourning rituals came up. So many religions, cultures, peoples have mourning rituals. But there seems to be a big subset of Americans who just… kind of don’t? Once a person dies, they’re put away, cremated or buried, and the bereaved have a brief wake or a funeral, and then… that’s it. They’re supposed to go back to real life. There’s no violent weeping, because that’s uncouth; there’s no beating of the breast, because that’s just so overdramatic; there’s no celebration of a life well- or poorly- or complexly-lived because how dare anyone stare too long at the concept of mortality. It’s simply un-American, it seems, because it’s too ugly, too unpleasant, too awkward and unruly. But death — death is part of life. Anyone who lives long enough, who is lucky and privileged to remain alive long enough to love and be loved, will mourn people.

Mourning rituals might not always be beautiful or comfortable or easy, but they tend to be, if nothing else, quite practical, and shivas certainly are. A shiva means that the bereaved are not left alone for too long, much as they might wish to be; it requires that they engage with the world just enough so as to remember how to function, just a little bit; it requires that others bring food to the bereaved, providing them with sustenance and removing the need to care for the self during the time of the most acute mourning. And, of course, shivas are places where stories are told: about the deceased, about their family, about other dead people, about memories long buried, about new life that’s recently come into the world. It’s such a deeply human ritual.

I absolutely hated my father’s shiva while it was happening, by the way. But in hindsight? I’m so, so, so grateful for it. For the snippets of it I can remember. For the ritual. For the sigh of relief when everyone finally left every day and my mom and brother and I could appreciate one another and love one another even more and even better.

How do you feel about your book, which is about grief, coming out at this moment of mass grief and uncertainty? How are you doing, as a debut author right now?

I don’t know, to be honest. I feel uncertain, like many others. I feel furious a lot of the time. I’m worried a lot of the time because of people I love who are living in places with a higher risk of COVID-19 exposure; I’m worried about the people I love who are exposing themselves day after day as a regular part of their jobs; I’m worried about the people I know who are currently sick.

It’s strange, amidst all this, to think about a book coming out, a debut, this dream come true. There are moments when I’m consumed by guilt and shame, as if having something to celebrate shouldn’t be allowed right now — but I also know, intellectually at least, that these useless emotions come out of the very same scarcity models and mentality that reinforce the structural inequalities the pandemic is further exposing. When I concentrate really, really hard, and try to practice what I preach, I can remember that human experience is too complex to allow any of us to live in a single emotion or a one-dimensional reality, and that’s when I can also remember that stories are important because they’re places we can escape into both alone and together, they’re places we can meet one another, and they’re places where we can, if we’re lucky, experience a range of feelings that we can’t always afford to deal with in our day-to-day lives. If my book is able to do that for some people in this moment of uncertainty and mass grief, then I’ll consider it a job well done.

What books are you reading right now? How are you keeping calm?

I’m reading some things for school and for work, but next up on my reading list are: finishing a manuscript by a hugely talented friend and colleague in my PhD program; finally reading Emma C. Eisenberg’s The Third Rainbow Girl and C Pam Zhang’s How Much of These Hills is Gold; and listening to the audiobook (which I have and just haven’t been listening to yet) of Sarah Scoles’s They Are Already Here: UFO Culture and Why We See Saucers.

I’m keeping calm in a few ways: needlepointing, which is the easiest craft there ever was, and which my partner’s mom finally gave me the perfect description for — it’s like the needlework equivalent of a paint-by-numbers! It requires absolutely zero talent, but it’s very soothing and a good break from my screen. I’m also watching The X-Files all the way through (I’m on season 4 now, and I have several dissertations I’d like to write on the subject) and have just started, years late, How to Get Away With Murder. And, of course, taking a leaf out of Maggie’s book — or her taking one out of mine? — a fair amount of smoking.

What do you hope readers take away from All My Mother’s Lovers?

I’m not sure that’s for me to say, really, but I suppose I can say that I hope readers take away from it whatever it is they need to, whether that’s recognition or catharsis or empathy or entertainment or escapism or any of the other myriad reasons we choose to turn to fiction.

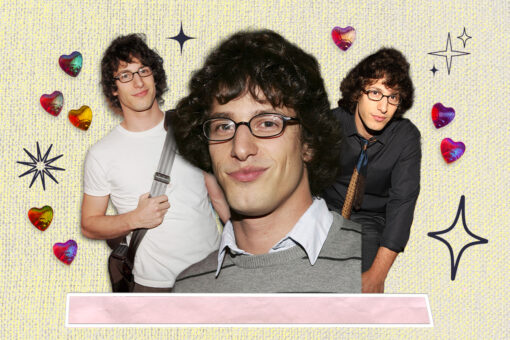

Image of Ilana Masad in header by Joshua A. Redwine.