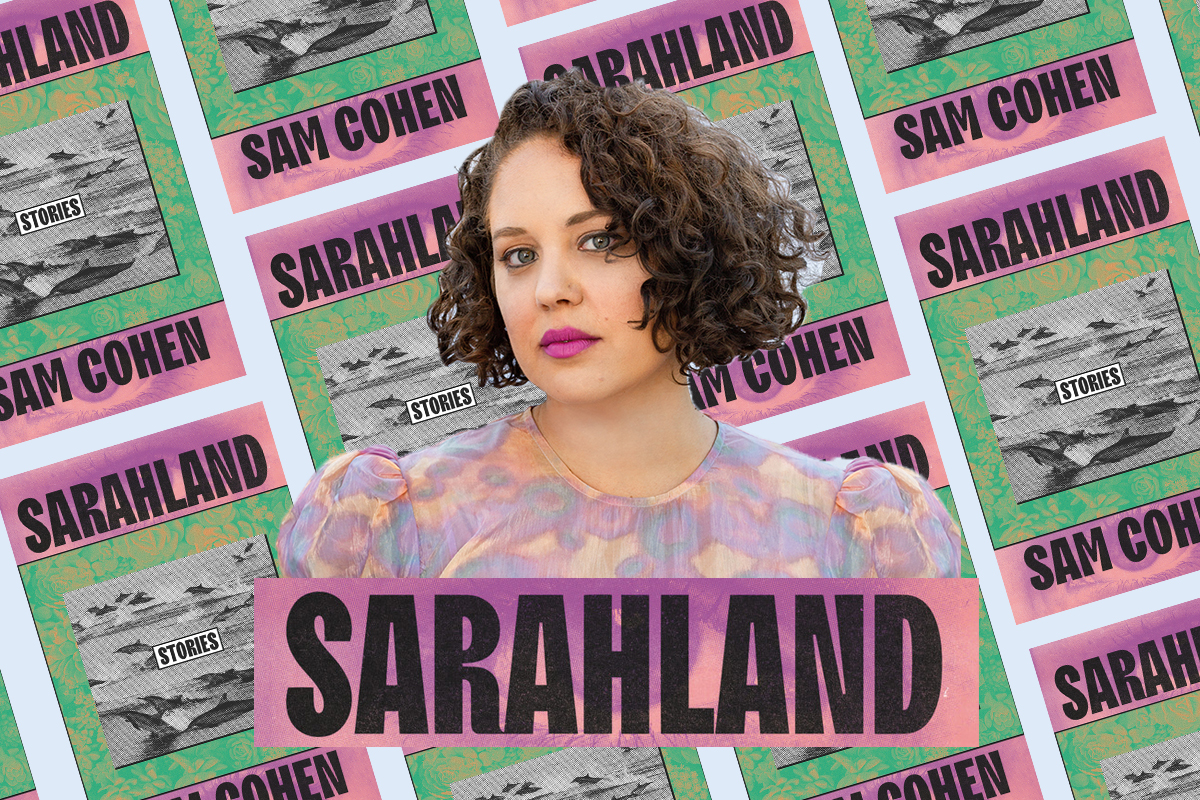

Sam Cohen’s inventive and smart short story collection, Sarahland, features 10 stories centered on women named Sarah. There’s a Jewish college student named Sarah dealing with hook-up culture and sexual assault. There’s Sarah of the Bible, who, in Cohen’s writing, is a trans woman who sleeps with Hagar to become the real parents of Ishmael. There’s a Buffy-loving Sarah who writes fan-fiction; there’s an aging lesbian Sarah who literally becomes a tree. Each Sarah is told through a queer, Jewish lens, with tenderness and care.

Sarahland, at its core, “is a book of stories that’s also about stories and storytelling,” writes Cohen to me over e-mail. “I do hope readers come away thinking about the stories that we inherit and the stories that we tell ourselves. In the best case, they feel empowered to some degree to rewrite their own stories.”

Ahead of the release of her debut collection, Cohen and I chatted Sarahs, witchy Judaism, and queerness.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Okay, first I have to ask: Why the name Sarah?

My friend Nikki Darling assigned me a piece in a collaborative project, The Four Horsegirls of the Apocalypse. She told me that my horsegirl’s name was Sarah, and was 12 years old. This prompt became “All the Teenaged Sarahs.” Simultaneously, I was working on “Exorcism, or Eating My Twin,” where the characters are named Tegan and Sara(h). I really loved how the two stories spoke to one another — in terms of complicated identity formation under patriarchy, disidentification with/communication via pop culture, the voice of the young girl — and I felt sure that they were two pieces of something larger: a book! At first I thought it was a problem that both narrators were named Sarah, and couldn’t really be changed in either story. Then, I thought, what if I just took the name Sarah as a kind of generative constraint and followed wherever it might lead?

Who was the first Sarah you knew?

I love this question and it made me realize that the name Sarah is actually part of my queer root. The first Sarah I knew was in preschool, her name was Sara Sahn, and she loved the colors black and pink so I insisted on only ever wearing the colors black and pink to school. When I told this story to my first girlfriend she told me to google her and was like, “I guarantee you she’s queer,” and it was true.

What was your favorite Sarah story to write? Why?

They all had really different pleasures and difficulties. A fun surprise is that the first story, “Sarahland,” was actually the last story added to the collection. The idea for the clique of Sarahs felt really fun, but I felt anxious about writing it because I knew that somehow it would connect to sexual violence. By the time I started, it came really easily and all at once, and it ended up bringing the whole collection together in a way that I didn’t understand before.

I loved how the stories covered the diversity of Jewish storytelling — from the Sarah at college in a Jewish dorm, to the original Sarah/Sarai. Do you think of Sarahland as a Jewish book (whatever that means)?

Totally, I think it is. I feel like being Jewish is very central to who I am and how I think in ways that I can’t at all articulate, but each of these stories came from a very personal place. I think that whatever a Jewish book is, Sarahland is absolutely one.

What do you remember learning about the story of Abraham and Sarah growing up? Why did you decide to write Sarah as a trans woman in Sarahland?

I don’t really remember learning about them. I guess I must have, I know that story, but I didn’t pick it because it was particularly formative or special to me — more because there was a Sarah in it. As for why I decided to make her a trans woman, there are a couple of reasons. One is that when I reread the story about Abraham and Sarah and was thinking about this couple that couldn’t conceive, it just made some kind of intuitive sense to me that maybe she was trans.

I’m also really interested in re-writing both the bible stories and some of the Darwinian stories (although none of the Darwinian stories are in this book) because they feel like they’re the only origin story options we really have, and they both make the gender binary and compulsory heterosexuality feel timeless and natural. It feels important to me to destabilize and upend that by insisting on origins that include gender and sexual diversity. When all of our origin stories are about heterosexual men and women (or cishet male and female animals) as though those are really natural categories, it seems like gender is real. And it is real, but it’s also a story.

I also adored the “Gemstones” chapter when the characters Ry and Jame became various famous Sarahs. Who do you think is your favorite famous Sarah, and why?

I love all of those Sarahs. Sarah Schulman is a genius and has articulated queer history and politics in groundbreaking ways. Sarah Silverman is so funny. She’s probably the first comedian I really liked. Sarah Paulson is the ideal human being. Sarah Michelle Gellar was Buffy. That’s not a fair question! I can’t choose a favorite.

Were you raised with Judaism? If yes, what kind of rituals/traditions were some of your favorites?

I was raised with Reform Judaism and I really loved all the rituals and I wanted to grow up and be Orthodox so that I could do them all, including the ones my family didn’t observe. But Passover has always been my favorite. I actually host a queer feminist seder every year!

What does your Jewish identity mean to you in 2021?

So many things, I could talk about that for a long time. But one thing in 2021 is that with some other Jewish friends, we’ve been following Rebekah Erev’s Jewish planner and there’s been something so amazing about being on Jewish time. My religion in adulthood has definitely been more witch-based and it’s been so incredible for me to discover that the Jewish calendar runs along the moon cycle, so that each month begins on the new moon and ends on the new moon.

And basically every major holiday is a full moon festival or a new moon festival, which has really changed the meaning of those holidays to me. It’s made me want to observe every holiday now that I can think of Purim as the full moon festival of wealth redistribution and drag, and Tu Bishvat as the full moon festival of the trees. So I’m in the process of discovering a Judaism that feels very not aligned with the God figure that I was raised with and that feels very right to me. And it doesn’t feel like I’m making it up, it feels like some of us are collectively discovering something.

If you had to do another book centered around a character’s name like Sarahland, what name would you choose?

I probably wouldn’t write a version of this book again, but I will say that before Sarah, I tossed around the name Veronica because I was thinking about Heathers and the girl who was not a Heather. I was thinking about what it means to be that girl, the girl who is a little outside who is trying to find her own path. I think those ideas stuck in this collection, but I liked the sort of every-girl name of Sarah.

How do you feel about releasing this collection at this particular moment in time?

For most of my life, deep questioning of gender and representation of non-normative sexualities were pretty fringe discussions. For me, it’s really amazing to put this book out at a time where public discussions about queerness, transness, rape culture, etc. are already happening. It feels like the book can be part of a bigger conversation than I imagined being part of, where, you know, my mom’s 70-year-old suburban friends already have a context in which to understand these stories, which might not have been the case 10 years ago.