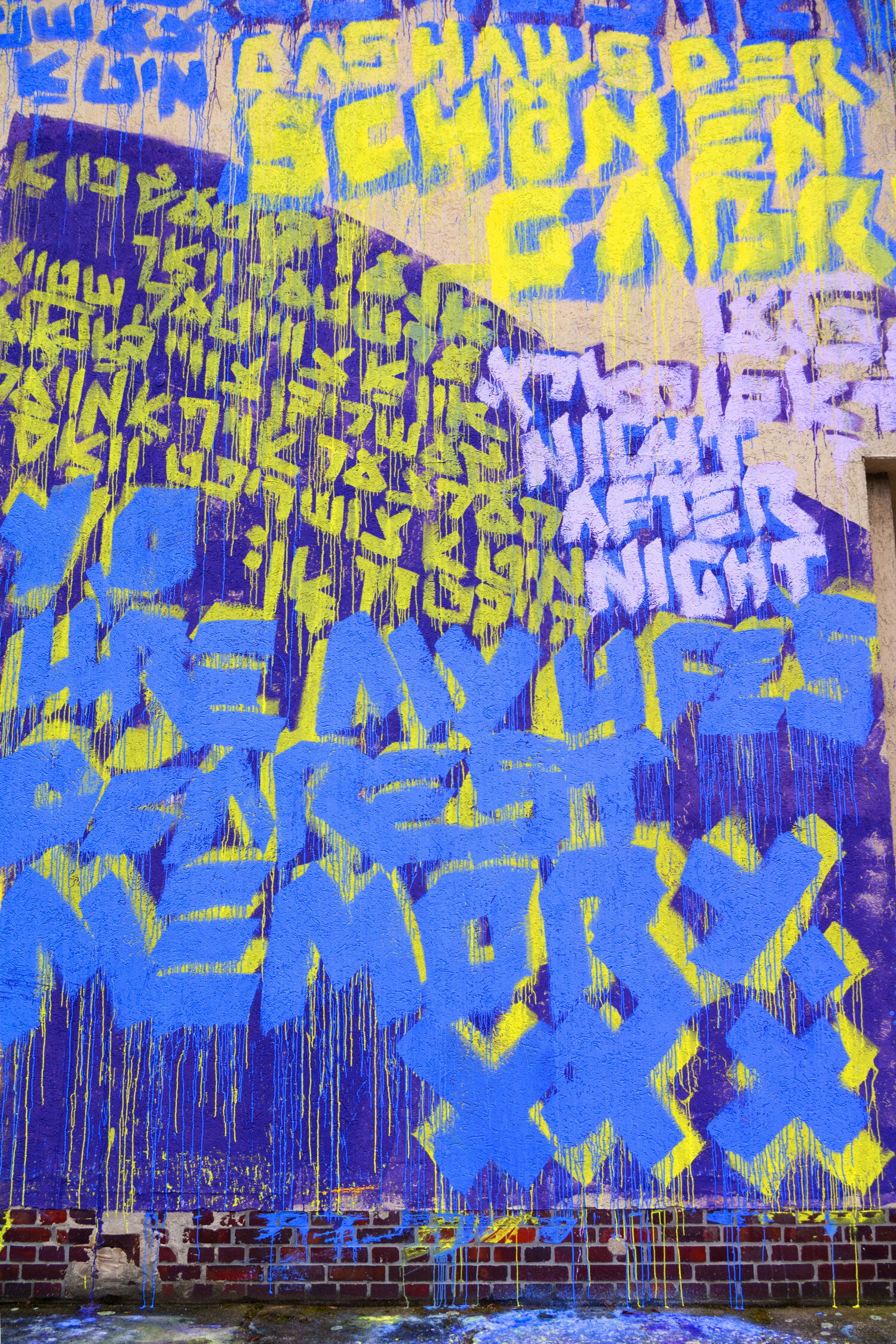

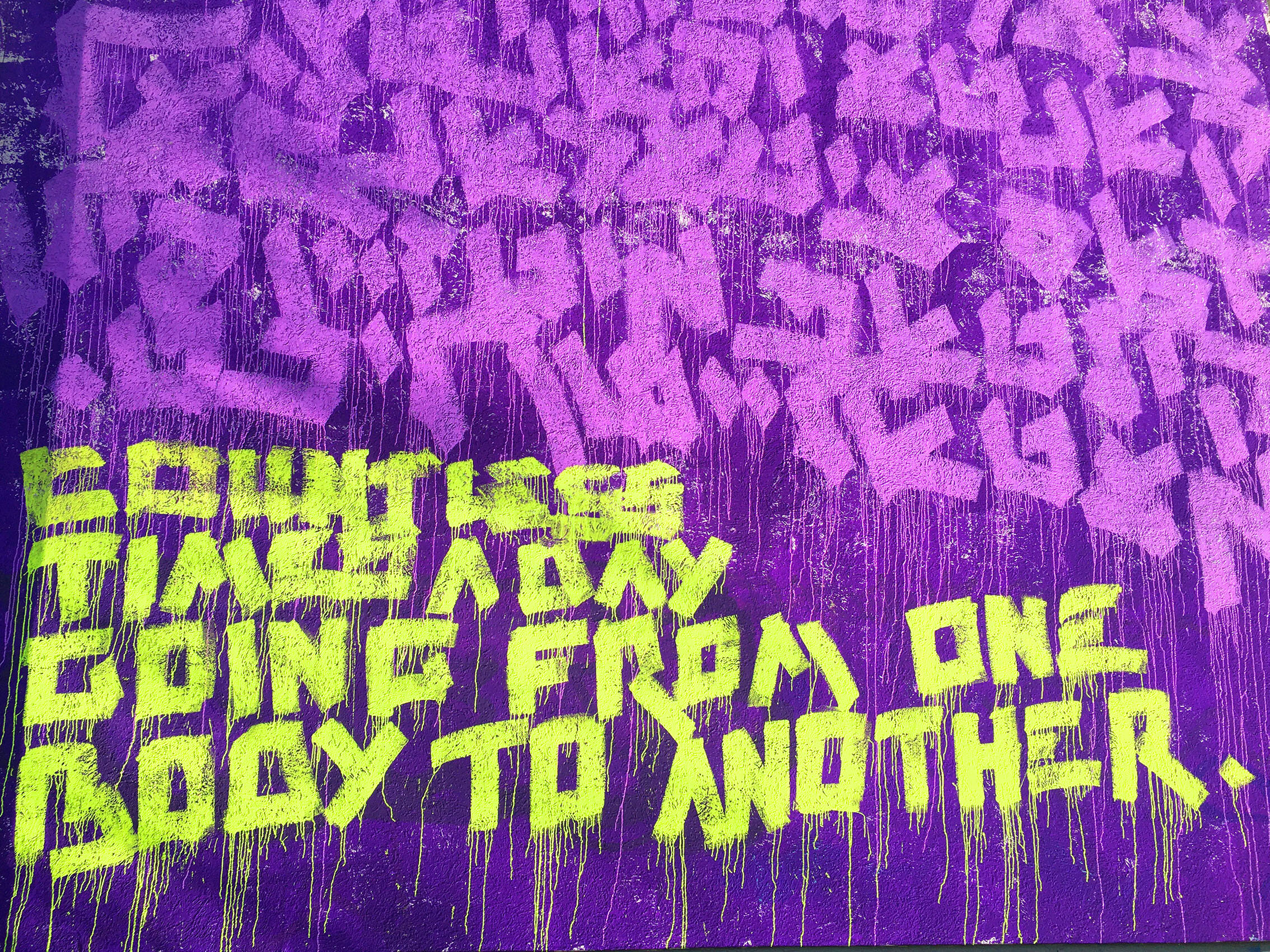

In March of 2021, visual artist Ella Ponizovsky Bergelson completed a series of murals in Berlin for her latest project, “Present Figures.” The works are site-specific interventions of “hybrid calligraphy” — an artistic practice which interweaves and mixes different languages and typographies. For these mural paintings, Ponizovsky Bergelson has fused Yiddish, Arabic, German and English words in a visually arresting manner. The result is a bold layering of geometric shapes with a bright color scheme that calls to mind neon signs and billboards.

The words that form the intricate patterns in the artworks come from poems by Debora Vogel, a poet who perished in 1942 during the liquidation of the Lwów ghetto. In preparation for “Present Figures,” Vogel’s poems, originally written in Yiddish, were translated into different languages and transliterated into their respective alphabets. The resulting texts were painted on the walls of residential buildings in three areas of the city. The boroughs Reinickendorf, Spandau and Tempelhof are suburbs, not part of the tourist trail or cultural hubs normally associated with Berlin. In these areas, it is rare to stumble upon large-scale public art, let alone art composed of Yiddish poems written in Arabic script.

From the 1920s onwards, Vogel had been part of a group of young avant-garde artists and intellectuals that were slowly bringing about a Yiddish Renaissance. Their movement was gathering momentum, not just in Eastern Europe but in Paris, New York and elsewhere. The group sought to make Yiddish a conduit for modern, bold and multicultural expression. But this Renaissance was not to be. The immeasurable evil unleashed during World War II ended the cultural movement before it had a chance to establish itself solidly enough to survive. As the 20th century wore on, much of the work was forgotten entirely, or talked about only in specialist circles.

But recently, there has been a revival of Yiddish-inspired visual art. “Present Figures” is very much at the forefront of that boom. Born in Moscow, raised in Jerusalem and currently based in Berlin, Ponizovsky Bergelson only (re)discovered Yiddish a few years ago — before that, she had no particular interest in the language. But in reconnecting with her own family history, she grew curious.

Ponizovsky Bergelson is the great-granddaughter of David Bergelson, a writer and a contemporary of Vogel’s who also wrote in Yiddish. As she explains to Alma, “When I finally moved more permanently to Berlin in 2016, this was the first time I really became interested in Yiddish and David Bergelson and the story of this generation that tried to use it as a literary language and not as a ‘home language,’ which it was. It came from this desire to find my own connection here. Then I had to look back at my family, who actually passed through here already. My grandpa grew up in Berlin and lived here until he was 14 years old, until they relocated to Moscow.” By tracing her family’s past, she discovered a new creative expression.

While the connection to Bergelson was personal, her connection to Vogel was more artistic, almost intuitive. Ponizovsky Bergelson calls the experience of discovering the poems, written by Vogel almost a century ago, as a “magic” moment. She connected instantly with the oeuvre and the artistic vision of her predecessor.

In writing her poetry, Vogel was inspired by the visual arts; she applied principles of modernist painting, abstraction and cubism to text. This aligned with the concept of hybrid calligraphy, which Ponizovsky Bergelson had already been practicing for some time, where she, inversely, applied a textual logic to visual art. “I felt a very strong connection to the strategy behind her choices. Especially language-wise. I felt that there was a simultaneity in how she works and how I work. […] As I was discovering Vogel and discovering how she worked, I realized I had to use her words. Then I could create some kind of loop effect … She was inspired by the visual and put it into words, and then I take the words and put them back into the visual.”

Learning about the previous generation of artists and writers who engaged with the Yiddish language was an eye-opener for Ponizovsky Bergelson. In reflecting on their subject matters, it became apparent to her that not enough had changed over the past century. Many issues and challenges of the past seemed to still inform the present: “This is when I started reading David Bergelson. I started digging Yiddish, trying to learn it, trying to read it — before that I had no interest. With Bergelson as with Vogel, as I was reading, I felt that a hundred years had not passed. [In these works] everything is very temporary, everything feels like a train station, there’s a lot of migrants and refugees and it just felt like now. I feel like we had similar inspirations, similar motivations and similar struggles.”

Ponizovsky Bergelson views Vogel and the other artists of the previous Yiddish Wave as iconoclasts. Choosing this language as their medium at a time when it made little logical sense to do so was profoundly (and implicitly) radical. Clearly, antisemitism was on the rise. But also, from a pragmatic, commercial point of view, what could the readership possibly be for literature written in Yiddish? Limited, to say the least. For Ponizovsky Bergelson, this showed that their motivations were not material, or somehow wholesale; they were resolutely artistic, and perhaps idealistic, too. This notion of iconoclasm resonated with her: Even before discovering this group of creatives, she always saw herself as outside the normative context of the traditional art world.

As a student at the Bezalel Academy in Jerusalem, Ponizovsky Bergelson already would not conform to what she calls her “strict” education in visual communication and graphic design. She was never going to allow strictness to become restrictive: “We were not allowed to use more than two typefaces for one work. And even then, I would immediately try to break that, to break the rules and prove to my professors that this works. You can use 200 typefaces in one image and it’s still going to work, from a design point of view. It comes from my natural instinct to break rules, defy authority and follow my gut.” The affinity for hybrid calligraphy, it seems, was already stirring during her student days.

In the murals that form “Present Figures,” the artist has successfully translated the non-commercial choice made by the previous generation of Jewish intellectuals into visual expression. While the murals might at first glance resemble advertisements, Ponizovsky Bergelson’s overriding message is clear: “Not for sale.”

“The color theme is definitely inspired by pop culture, fashion and ‘the commercial world,’” she explains. “For me it is about using this strategy, the blow-up, this huge size of a mural and these vibrant colors, really vivid colors, which are calling for attention and no one can ignore them. But [it’s not] advertising, because there is nothing to sell here. The murals are hard to decipher or actually read. You have to research a bit to understand the content and what’s written on them.”

Refusing to “sell” ultimately means refusing to give people what they want, since wanting is the basic principle of buying. In “Present Figures,” Ponizovsky Bergelson is not looking to seduce the viewer into sharing her convictions. She is simply expressing a personal vision: “In the past five years, living in Berlin, I’ve tried to be less of a ‘good girl.’ No more polite works. Obviously, there is a lot of rage and intense emotion. The color reflects that — I would even say they’re aggressive colors.”

When asked if the rage is directed towards the past or the present, she states, “There is no difference. When you dig under the surface, very little has changed and perhaps only superficially. Life in Berlin seemed very bright and beautiful to me, also because of the hard past. [I used to think] this was truly an emancipated nation, because they have made all the possible mistakes and now, they are learning. But then, eventually, living here and being part of this system … I work here, I have love relationships here, I have friendships here, and I realized … there’s still a lot of work to do.”

The non-conformist spirit of the past generation is clearly integral to “Present Figures.” In the same way that her predecessors challenged the social and political climate of their time, Ponizovsky Bergelson, too, uses her hybrid aesthetics to comment on what she sees around her. “I’ve been told that mixing languages is wrong. When one speaks one language it should be correct, you shouldn’t borrow words, even though people understand you, you still can’t do that. […] When I translate Yiddish into Arabic, there’s already a statement there.”

“Present Figures” is full of tension — between the past and the present, between incompatible scripts and languages, between opposing cultures. And like anything full of tension, it feels like it could snap at any moment. Ponizovsky Bergelson is not afraid of this. Her rebellious spirit seems to anticipate and encourage destruction.

Her subject matter serves this attitude well. One tragedy of the previous century’s Yiddish culture is that much of it was lost when its authors either migrated or were murdered. This transience has been integrated into the murals. Ponizovsky Bergelson has an agreement with the owners of the buildings where she has painted “Present Figures”: The murals have to be painted over within a year. Soon, the words will disappear from the walls. “The idea behind almost all the murals that I do is that they have to be temporary. They are not monuments and they are not there to stay.”

She has employed this practice in previous projects, too. “Among Refugees Generation Y,” completed in 2019, was another series of public space installations that she painted elsewhere in Berlin. For that project, she used only one sentence from David Bergelson’s short story “Among Refugees,” repeating it over and over again. Some of those murals were painted using lime wash, made to fade over time. Others were painted onto ceramic tiles using paint that peels off. From the outset, these pieces were destined to be short-lived.

It is not strange that brevity and destruction underpin these projects. Both Debora Vogel and David Bergelson disappeared too soon, and violently: Vogel at the hands of the Nazis, and Bergelson in 1952, during the Stalinist massacre historically referred to as the Night of the Murdered Poets. And considering more recent history, there is no place like Berlin to stage the disappearance and destruction of walls.

While these interventions might not stay around for long where they were originally created, they soon reappear elsewhere. After “Among Refugees Generation Y,” and now that the current “Present Figures” murals are complete, Ponizovsky Bergelson is heading to Krakow. In Poland, she will do another series of murals, again based on a hybrid calligraphy rendering of Vogel’s poems. The project is scheduled for May this year. She views this string of mural series painted in different locations and cities as “stops along the same route.”

Next year, she has her sights set on Marseille, another hotspot of cultural and linguistic hybridity — and tension. In France, she hopes to look beyond her own heritage and engage with other cultures which have defied established narratives and been marginalized as a result of that historical nonconformity. It will no doubt be exciting to see how and where Ponizovsky Bergelson’s future projects appear, and what vanishing acts she will try next.