Kali Spitzer vividly remembers one particular piece of art that hung in her childhood home — a collaboration between Linda Frimer, a Jewish artist, and George Littlechild, an Indigenous artist, which was part of a project called “In Honour of Our Grandmothers.” That image mirrored Kali herself, who is Jewish on her mother’s side and Kaska Dena Indigenous on her father’s. “I always grew up thinking they fit together and thinking that they potentially inform one another, or have this intersectionality,” she told me. “I’ve always been like, well, I’m Indigenous and Jewish. So the art that I make is Indigenous and Jewish.”

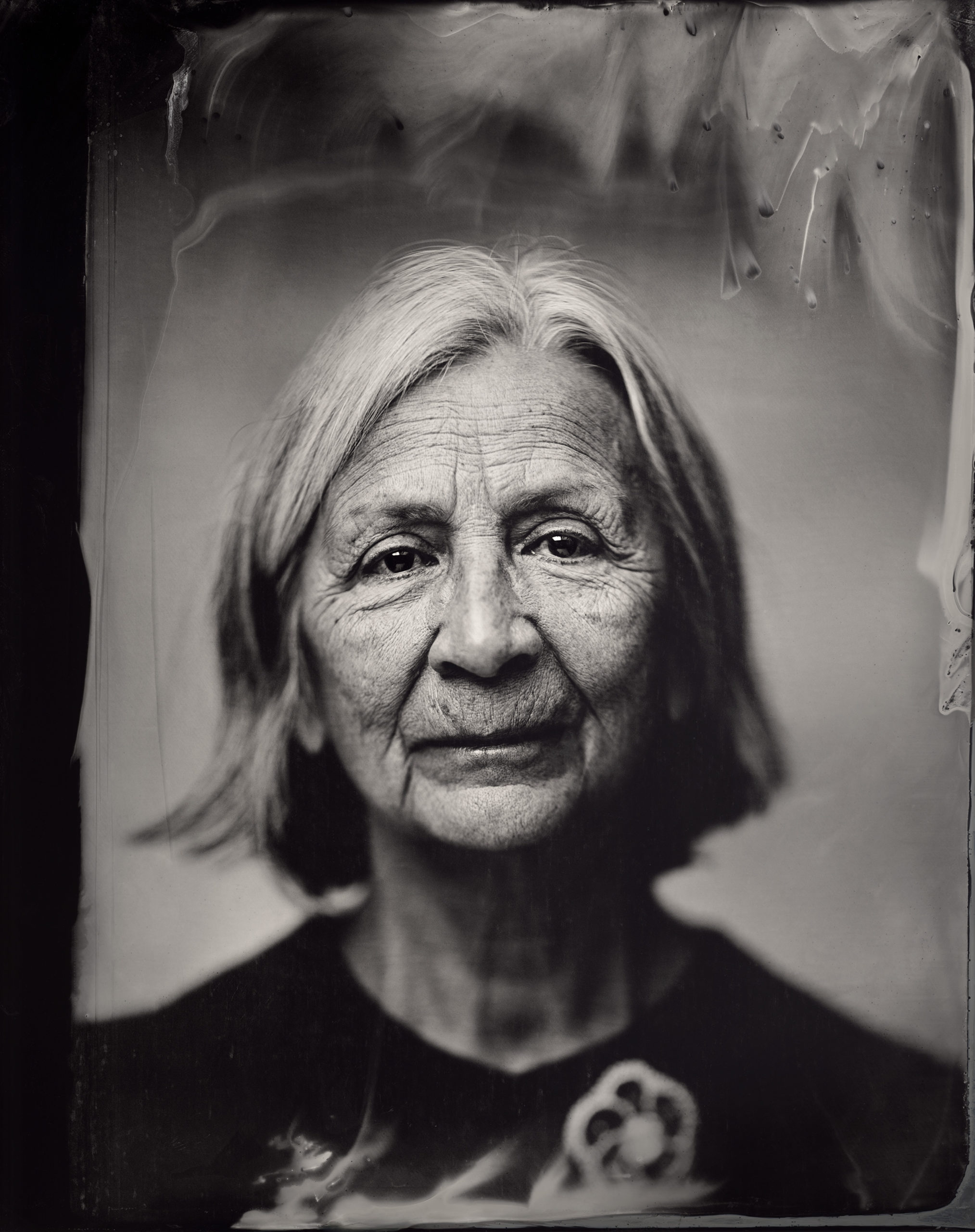

That art mostly takes the form of photographs, both on traditional film and using a wet plate process — more on that later. Per her website, Kali’s imagery “embraces the stories of contemporary BIPOC, Queer and trans bodies, creating representation that is self determined. Kali’s collaborative process is informed by the desire to rewrite the visual histories of indigenous bodies beyond a colonial lens.” Her heritage “deeply influences her work as she focuses on cultural revitalization through her art.”

She makes “portraits, figure studies and photographs of her people, ceremonies, and culture. At the age of 20, Kali moved back north to spend time with her Elders, and to learn how to hunt, fish, trap, tan moose and caribou hides, and bead. Throughout Kali’s career she has documented traditional practices with a sense of urgency, highlighting their vital cultural significance.”

Kali spoke to me from her home in what is now known as Canada. She shared her Zoom frame with a giant cactus, a holdover from her years in New Mexico and Mexico. We discussed the fraught history of photography, where her family comes from, and how her images grow out of love for her community.

Anything you want to say to introduce yourself?

I usually start by acknowledging that I’m an uninvited guest, living on the traditional lands of the Tsleil-Waututh, Skxwúmesh and Musqueam peoples. And I’m grateful to be living and working on this land.

Thank you. I wanted to start by asking: What draws you to the process of tin type photography? Some of your images seem to reference other photographs from history that were taken by colonizers with much less generous and inclusive aims. Did they use a tin type process?

The formal name for the process is wet plate collodion process. I’ve always loved that process. Because I do it on aluminum, it is called a tin type; if I did the same process on glass, it would be called an ambrotype. I have historically moved a lot, so I haven’t wanted to transport glass plates. So I’ve been using aluminum.

The first gripping wet plate work I saw was Sally Mann’s self-portraits when I was younger, and I was very drawn to them. I used to do silversmithing, I love metal — it combines metal and photography, which is really beautiful and alluring to me. I was taught this process by my mentor, Will Wilson, who is an incredible photographer and has opened a lot of doors and been instrumental in my career. We have a really good working and personal relationship. In Will’s practice, he’s definitely done work as a direct response to Edward E. Curtis’s work, which could be part of that conversation of how photography has an inappropriate, and at times violent, legacy, especially for us as Indigenous folks and Black folks and people of color.

For me, it’s more a love of process. The entirety of my practice is a response to the harmful legacy that colonization has left through mediums like photography, which was used as a pretty violent taking tool. And so a lot of my practice is to heal and correct that, for myself and the people that I’m working with, within my community.

What draws you to a subject when you choose to photograph something in series?

Actually, that’s a great question. Usually, I try not to use the word subject. I’ve made mistakes to get to this point — I think it’s really important that we talk about how we’ve learned and grown. I’m trying to be really careful about the language I use. So, I don’t use subject; I usually try not to use “taking” a photo, because we’re really working together. Most of the people that you see images of in my work are friends and family and people that are close to me. I think that the work I’m trying to make is really vulnerable, and so there needs to be an element of trust. Especially when a lot of us do have complicated relationships with photography, it can be super objectifying.

It’s complicated to make your artwork with and from other people. I still make mistakes. I find, even if I’ve known the person for 10 years, I get to know another facet of them through photographing and working together. It’s not that we make the photos together and then the conversation ends. It’s actually a lot of emotional labor and space that I’m so happy to provide and hold, and that is also taxing, for sure, but not in a negative way.

That also contributes to how slowly I want to work, because I’m learning about intimate parts of people. Maybe there’s an emotional reaction that you want to be there for the person to carry out. And then also checking in with people, being grounded in consent around where their image goes, that also continues the dialogue for quite a long time.

That thinking about the vocabulary is important, especially since a lot of this vocabulary is rooted in problematic historical experiences. And also, you are working with the real stuff of somebody’s life and image.

I’m protective of that. I’m honored that people trust me. And then I really don’t want anybody to have a negative experience. I really go to bat for that person, you know?

So how do you establish safety in the photographic space? If you are already close to the people that you are photographing, there is already some level of trust and affection, but what is the process like? I’m sure it’s different for each person.

I don’t think I can make someone feel safe. I can help them, though. I view it as a huge part of my job to listen and to try to anticipate some of these needs. Usually, we’ll have a phone conversation or a conversation in person before we even go into the studio. We visit, we talk about it; I ask them how they want to be photographed. It definitely still has my eye; I don’t want to negate my artistic vision. I also view it as a collaboration as well; I think that it can be collaborative to a certain point. It is my eye, but if somebody doesn’t like their image, or they want to change it, we do that. And that’s a really beautiful part of wet plate collodion process, which I’ve previously referred to as the fanciest Polaroid in the world. You hand-pour your emulsion on the plate, so you make your own film. And then you sensitize it, and then you load it into a film holder, and then you go make the exposure with UV light through strobe or ambient sunlight. And then you develop it right away. Depending on the weather, you have, let’s say, up to 15 minutes. So my favorite part, the magical part, is going in the darkroom with the person and watching it develop together, and seeing that person’s reaction, whatever it may be. And therefore being able to also change the image from there.

Somebody might think they look like their grandmother, or feel like they’ve never been seen accurately like that. Occasionally, someone’s like, “oh, I don’t like that.” That’s great, too — we get to change it, and so it really does feel collaborative in those moments.

That’s incredible. I feel like it’s historically been so rare that the person whose image is part of the art actually has input or can respond to it as it’s being made.

Something tactile, too. Digitally, you can look at the screen and show somebody what you’re working on. But that’s not usually the end product — and it’s different to be looking at a tiny screen versus an 8 x 10 inch plate.

I want to shift a bit into your personal background. Can you tell me about your family history, where the Jewish and Indigenous sides of your family come from?

My mother is Jewish on both sides, with roots in Transylvania, Romania originally. My mom actually went back a few years ago to where we’re from, and there was only one Jewish person still there in the whole town. I wish I had gone with her.

My maternal grandparents moved from Brooklyn. They emigrated to Canada when my grandpa was around 40 because he was wrongfully jailed in the McCarthy era. I can’t remember if it was the CIA or FBI, but they just took them out of the store where he worked. My grandma didn’t know what had happened. They jailed him for being a “communist.” He was a scientist at the time working with Linus Pauling and, I believe, Madame Curie. He got blacklisted and couldn’t work anywhere, so they immigrated to Canada and didn’t go back to see their family for 15 or 20 years. He went to medical school at 40 to start a new career. He passed away at the age of 100 and a half.

He was raised religious, but they didn’t raise my mom and late uncle religiously. They were incredible people — really valued art, fought for mental health rights, for gay rights. Just very progressive people. I feel very lucky on both sides of my family that way. And so I had tons of support from them, financially and emotionally. They always encouraged me to go for the arts and what I was passionate about — and good at, as well. I have pretty severe learning disabilities, so being a judge or a lawyer quickly went out the window for me. Or a nurse — you cannot be a nurse and be dyslexic.

Then on my father’s side, we’re Kaska Dena. He was born on the land and raised on the land with his mom and siblings and language. And then he was stolen at the age of 5 to residential school. He ran away successfully at 15. He can’t speak our language anymore — it was beaten out of him, among a lot of really atrocious things that I don’t like to get into. It’s his personal story. He also really values art; he also fought for gay rights, and definitely used to have incredible politics. So I grew up with a really good foundation in that way. And then I grew up with a lot of lateral violence and effects of colonization as well.

Do you perceive any overlap between these two cultures that made you?

Yes and no. I think that’s a really complicated question, too. On a cellular level, I grew up with a lot of anger. I’m a recovering alcoholic, and I remember my mom being like, “what is going on?” She didn’t get it, and I didn’t get it either. And then I think as I got older and understood intergenerational trauma, I was like, “OK, this stuff lives in me from both sides.” Even though it was so much more recent with my dad and more ongoing — the injustices that happen to Indigenous people today and that are ongoing are much more horrific and prevalent where I live than antisemitism and there hasn’t been a lot of time to heal, there hasn’t been the same acknowledgement.

Both of my cultures have experienced intense genocide. That’s where I draw a parallel. But I think it’s quite different. It becomes complicated to talk about, because there are so many different kinds of Jewish people. There are people, like me, who are Jewish and Indigenous. So it becomes a complicated conversation for sure.

I don’t want to speak to anybody else’s life experience. I do draw the parallel of both having gone through genocide. And then if we get into a bigger conversation, most of us, in one way or another, are here because somebody’s gone through a genocide. So I find parallels and then I also find it quite different.

Is your Jewishness part of your life daily? Do you feel it? And if so, how?

I was never raised religious. My mom raised me as an atheist. I definitely have my own belief system within the land. I feel Jewish, I “look” Jewish, it’s part of me culturally. I’m not religious. I do not align with Israel at all.

I’ve never positioned myself as a religious person in any religion. But my Jewish side of my family was the one that was around more, that raised me. Not to say that that created any disconnection to my other culture. But it is something that I feel close and connected to — just not through religion.

What feels Jewish about you, to you? Or is that too difficult a question?

Whenever I say I’m Native to people, they say, “Oh, really? You don’t look Native. Clearly you’re Jewish.” But I eat bacon on the daily. Seriously though, I think it’s just really nice to feel part of a community. Actually, through this pandemic, I have been a lot more connected to other Jews and have been on a few calls about racism within the Jewish community. I feel it in my bones, I see it reflected in my family and I feel very proud to be Jewish.

Do you think you might ever explore Judaism or your Jewish heritage in your work? Hearing about your mom’s experience going back to Romania makes me wonder if there’s something there, in addition to the work you’re doing with your Indigenous community.

Yeah, I was actually just asked by the Lonka Project to photograph a Holocaust survivor. I was really excited about that — that is something that I would love to do. We’re still in conversation about that project. There are a lot of different photographers doing it all over the world.

I feel like my being Jewish informs the work that I do. That said, the communities that I’m part of, at this moment, are queer, Indigenous and BIPOC communities. I feel that there’s so many injustices that are continuing to happen to those communities that are really prevalent. And so for the moment, I really want to focus on amplifying our voices and amplifying our visibility.

That’s not to say that I wouldn’t do a series of Jewish kin. I think what that might look like more is folks of color that are also Jewish. For example, I photograph myself, but how many white-presenting, female-presenting bodies do we need out there? But then we get into conversation of tokenizing, which I feel a lot in my work. I would never want to do that to another person. And so I don’t have a straightforward answer, I guess.

Are you close with other people who are both Indigenous and Jewish, who are part of your community? Do you talk about these things with them?

Yes. Audrey Siegl, whom I photographed, is Jewish and Indigenous. And then I definitely have a community of people. I met Carmel Tanaka, who is an incredible community member here. She’s Japanese and Jewish, and she has been the person who’s really been opening up my community of Jewish folks and Jewish folks of color. It’s been really wonderful to start growing more involved and realizing how expansive it is on both sides.

Identity erasure happens within our Indigenous communities as well. Afroindigeneity is often erased, and it’s not OK, and it’s not fair. We need to be lifting our kin.

You do a lot of work around queer bodies as well. Are there organizing ideas or overlapping qualities across all your photographs, or is it all growing organically out of who makes up your community?

I think it’s just growing organically out of who makes up my community, really. It’s not that I have an idea in mind of photographing a certain kind of person, it’s that I want to represent my community accurately. So I’m working with people I feel close to that are around me. And a lot of those people are really monumental pillars of our communities.

Have you had any experiences of Jewish spaces, positive or negative, that you want to share? I know you weren’t religious growing up so you may not have had many.

I have been in Jewish spaces when we traveled as a family, but never really went to services or anything. Although my mom did sign us up for a synagogue when I was young — the rabbi was marrying same sex couples and she wanted to support that because there was some community backlash. So we did go to synagogue to support that. And then I do remember traveling to other countries and going to visit temples. One time when we were in synagogue, we either couldn’t go in, or we had to leave because there was a bomb threat. I also used to go to Jew camp when I was younger, where lots of people spoke Hebrew, and I felt out of place in that way. There were a lot of watersports and things, which is where I thrive. But we also got a bomb threat.

Oh, wow. Are there any specific stories or experiences of making an image with someone that you want to tell?

I want to speak to Audrey’s portrait because I have permission — she’s Indigenous and Jewish, among other ancestry as well. She’s Musqueam. So this is her territory that I’m living on. And we actually really became friends through the process of photographing her. The Bill Reid Gallery here commissioned a few portraits of her to honor the work that she’s done. She’s quite amazing. And her sister Maria had passed on eight weeks before we made the photos, which was not expected.

So this was a bit of a different scenario, because we didn’t know each other well. We started the process slow. She came in; I asked her how she wanted to be photographed. I obviously used a lot of care and slowness in her grief. And we feel like family now — she’s one of my favorite people ever. She made me cry when she talked about those moments of being photographed. She thinks that it is the most accurate image she’s ever seen of herself; she thinks she looks different than in all other images. She’s had a lot of compliments from her community. And I think that together, we were able to provide a safe and healing experience for both of us. It was a beautiful example of it going really well. She felt cared for, we made an everlasting bond and she felt represented accurately and that her sister’s spirit was also cared for in that space. It was really ceremonial as well.

The fact that she gets to look at this image of herself and feel super proud and strong and vulnerable and see the grief and all the different facets —that’s what I want. I want somebody to feel seen accurately, in everything, and also uplifted. I used to say empowered, and I now think that is inappropriate, because I’m not giving power to anybody. I’m just using a space that I exist in to amplify.