In recent months, the persecution of Uyghur Muslims in China has finally picked up media traction. The stories of a people being rounded up, loaded onto trains, and imprisoned in concentration camps because of their ethnic and religious background set off alarm bells for many, describing a scenario all too familiar to many Jews.

The alarming similarity to the Holocaust has been remarked upon by both Jewish and non-Jewish people alike, and on the internet, there has been a definitive uptick in comparing the situation in China to the Holocaust.

Holocaust comparisons are not new, and while most operate from spaces of both sympathy and action, they also highlight an increasingly troubling lack of education surrounding the Holocaust, demonstrating the negative impacts of comparing genocides to each other.

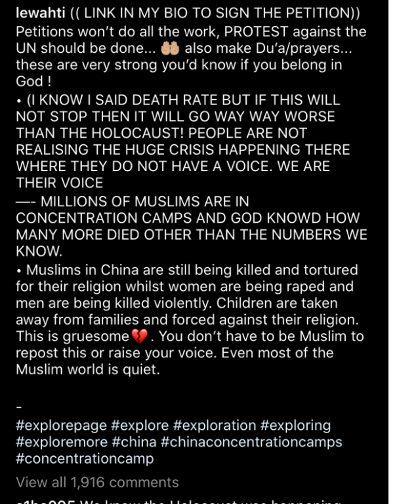

Take this post, for example:

This tweet, reposted on Instagram, went viral as a call for both sympathy and action, stating, “China has officially PASSED THE DEATH COUNT of the JEW VICTIMS IN THE HOLOCAUST with MUSLIMS in the CONCENTRATION CAMPS yet everyone is silent.” It uses the Holocaust as a comparison point to do so, unfortunately engaging in antisemitism in the process. If we can manage to look past the odd phrasing of “JEW VICTIMS” (oy), we find something more insidious lying within the foundation of the post itself. In attempting to garner sympathy for a persecuted people, posts like these — usually unintentionally — build upon miseducation surrounding the Holocaust. This results in a convoluting of the conversation on currently unfolding genocides, rather than the catalyzing of action, because it not only operates on false history but also objectifies suffering as a means for hierarchical comparison.

The post above, for example, compares the persecution of Uyghur Muslims to the experiences of the Jewish victims of the Holocaust via the notion that garnering public sympathy will put preventative action into place.

“I think using the Holocaust to evoke sympathy for genocides we’re talking about now is interesting, because it didn’t evoke much sympathy at the time,” Dr. Zoe Waxman, a historian, author, and Senior Research Fellow at the Oxford Centre for Hebrew and Jewish studies, explained to me.

Current mainstream Holocaust education generally seeks to pedestal nations like the U.K. and the U.S. for their help in ending the war, rather than educate younger generations on the actual events of the Holocaust. Dr. Waxman notes the current British media covering of the Kindertransport – the taking in of Jewish refugee children by the UK just prior to World War II – as an example of this, spotlighting the British focus on a “minuscule effort” as a distraction from historical responsibility.

“We don’t want to think about the fact that it was practically impossible for the Jewish survivors to reach Britain in the after-war periods,” Dr. Waxman states.

This stands similarly true to the U.S., which saw the turning away of thousands of Jewish refugees during the war, a fact that is regularly left out of American teachings on the Holocaust. Revisionary teachings that iconize the Allies as the heroes of World War II and the saviors of Holocaust victims are favored over those that offer a more nuanced education on the difficult position of the Allies both during and after the Holocaust.

When Holocaust comparisons are made on the idea that victims were offered sympathy as the Holocaust occurred, they operate on a false understanding of history itself. This same revisionism and miseducation has led to “almost two-thirds of young American adults not knowing that 6 million Jews were killed during the Holocaust, and [that] more than one in 10 believe that Jews caused the Holocaust,” according to a recent study.

Revisionist miseducation on the Holocaust doesn’t just affect our understanding of the individual event, but also obscures the historical basis for our understanding of how current genocides may be arising and the effects these genocides have on their victims.

“Using the memory of the Holocaust sidetracks the argument. I don’t think it encourages action, I think it encourages inaction,” Dr. Waxman explains. By inserting one genocide into the conversation of another, it scatters the energy that could have otherwise been focused on a current genocide as a means of catalyzing action.

Essentially, Dr. Waxman continued, victims of historical genocides quickly become lost in “a babel of conflicting voices trying to theorize different positions when actually, we’re not thinking about the lived experiences of the very people we’re talking about.” When the suffering of a people is introduced into that of another as a means of comparison, it diminishes the suffering of both. Rather than focusing on the victims of the currently unfolding genocide, it becomes a debate on who had it worse — what Dr. Waxman calls “unpleasant and unnecessary hierarchies of suffering” — completely undermining the entire conversation.

“We bring the trauma of one event into our responses to another and I think part of the problem of not understanding trauma…is that we don’t take trauma seriously and we don’t really understand the effects of revisiting it in the present,” Dr. Waxman concludes. These comparisons sidetrack vital conversations on action that should be taken to stop the specific persecution of Uyghur Muslims in China.

Attempting to compare one genocide with others will always result in the inevitable diminishing of the victims’ suffering — precisely because they cannot be compared.

If we truly wish to take trauma seriously, we mustn’t engage in undermining and comparison. Instead, we must honor victims of genocides passed by pushing for ensured access to accurate and humanitarian education, and fight for victims of current and arising genocides by catalyzing action.